In the fall of 1994, I fell under the spell of two powerful forces: love and Music. Not lower-case music; that had hooked me years before, but Music, as in the debut studio album released by 311 the previous year. For me, growing up in northeast Nebraska in the 1990s, Music came to symbolize teenage love and state pride—emotions I never imagined would matter to me as much as they did.

Before going any further, I feel like I should make a confession: prior to this essay, I hadn’t listened to 311 since 1996. As such, all of the band’s work over the last 20 years—eight studio records, two live albums, a greatest hits compilation and a box set, not to mention countless shows across the globe—has not been a part of my consciousness.

But it has been for legions of devoted fans, many who consider themselves part of an extended family (the “311 Familia,” as they sometimes call themselves). A similar feeling of interconnectedness grounds the band members, who’ve often cited their longstanding brotherhood as a key reason they continue to make music. They consistently tour and release new albums (there’s rumor that a new one may be out next year). Biennially they host Caribbean cruises and celebrate “311 Day” in March (on the 11th, duh). For this year’s celebration, the band played two arena shows in New Orleans to 15,000 fans, performing 85 songs from their 25-plus-year career.

Whew.

photo by Marina Chavez

I’m not interested in assessing whether 311 is “good” or “bad” music, if their songs are profound or lame. Those conversations have played out since the band’s earliest days. Instead I want to explore why a group that came to be acknowledged as one of the quintessential rap-rock “bro bands” of the ’90s made such an impression on me as a 16-year-old girl. I suspect the answer is simmering in a stew of teenage emotions and quest for self-understanding.

The process of writing this essay has been humbling for me. It has made me come to terms with why, 20-some years later, I find it difficult to admit that 311’s music meant something to me. It’s exposed many personal anxieties about coolness that I—apparently—still have. But I’m grateful for this insight. It pushes me to be a more self-aware listener and writer, a sharper evaluator of my tastes and a more attuned interpreter of my memories.

So, with all of this in mind, let’s talk about Music.

Love and music

photo by Melodie McDaniels

Similar to how Green Day and Blink 182 shifted punk into the pop arena for teens in the 1990s, 311 introduced many of us to reggae and dub. In 1994 the only reggae I knew was Bob Marley’s Legend, a compilation album owned by nearly every guy in my high school. (I don’t remember any other reggae records, nor do I recall many girls owning Legend, but that’s an essay for another time…)

Anyway, 311 mixed reggae with rock, funk and elements of rap. The combination of bouncy dub, heavy power chords and playful bass lines left 16-year-old me in awe: how had five dudes from landlocked Nebraska come up with such funky vibes and a unique sound?

My introduction to the band started with “Paradise” and “Do You Right,” two tracks from Music that my high school boyfriend Phil put on the first mixtape he made me. Shortly after we started dating, 311 became our thing. Phil schooled me on the band’s history—its birth in Omaha, early recordings in basements and local studios, first show opening for Fugazi at Sokol Auditorium, move to Los Angeles and eventual signing with Capricorn Records.

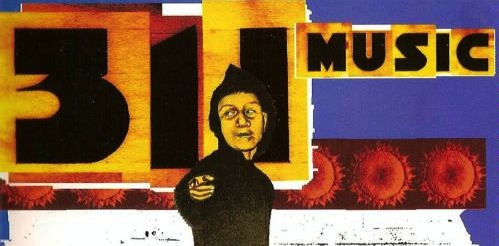

Phil knew the words to every 311 song. He’d seen 311 play at the Ranch Bowl in Omaha and knew guys who had smoked weed with the band after the show. In the oversized hoodies and baggy pants he wore, he often resembled “Herb,” the illustrated character on the cover of Music.

Even though 311 had released Grassroots that summer, Music was my preference. It resided permanently in my CD player for most of my junior year. When I first heard S.A. Martinez confess, “Music’s what I need to keep my sanity” in the song “My Stoney Baby,” I immediately jotted his words into my journal of significant song lyrics. They appeared after John Lennon (“And we all shine on / like the moon / and the stars / and the sun”) and were soon followed by Adam Yauch (“To all the mothers and the sisters and the wives and friends / I wanna offer love and respect to the end”).

For our first Christmas together, Phil gave me a copy of Unity, the 1990 independent release the band recorded in Omaha. Specific instructions accompanied the gift: Hold onto this, I was told, only 1,000 were made, and this CD was sure to be a collector’s item.

Our trips to Omaha often included drives by Westside High, where most of the band members had attended school, and La Casa Pizzeria, their favorite hang-out. I always hoped our excursions would take place on a weekend that P-Nut or Nick Hexum would be home visiting family and friends so we could run into them. (This never happened.)

311 meant much more to us than funky beats and party jams. The band members had their roots in the same soil we did. We banked on them to take us where we felt we couldn’t go at the time—into the bigger, cooler world of music that we knew only through MTV, 101.9 FM The Edge, Grand Royal Magazine and the alternative music sections of our favorite Old Market record stores.

And, soon, they did.

Homegrown celebrity

photo by Melodie McDaniels

In 1994 I knew of only a few Nebraska musicians who had “made it big”: 1960s one-hit wonders Zager & Evans, guitar hero Matthew Sweet and holiday seraphs Mannheim Steamroller. 311 was certain to be next.

A little bit Red Hot Chili Peppers, a little bit Sublime, with a dash of the Beastie Boys and the heaviness of Faith No More, 311 somehow managed to simultaneously kick ass and spread joy through its songs.

The music didn’t ask much of its listeners: just chill, love each other and party together. It seemed to come from a place beyond hate and violence, beyond exclusion, beyond bitches and hos, where all that really mattered were family and friends, a community of love, good herb and positive vibrations from the tunes on your stereo. It might sound silly, but as a girl, there was room for me in this universe. I couldn’t say that about a lot of the rock music that I was exposed to in the mid-90s.

The day their self-titled blue album hit the shelves in July 1995, Phil skipped summer school to buy a copy. He wanted to be one of the first people in our hometown to hear it. After class we sat in my car the high school parking lot with the air conditioner blasting and Mountain Dews in the beverage holders. We popped the disc into my Discman and listened as the band launched into the first track, “Down,” a song that would hit #1 on Billboard’s alternative songs chart and become a mid-90s’ party anthem across the country.

The blue album was just what we’d hoped for: spirited and peppy like their previous albums, a trippy blend of reggae, rock, hip-hop and ska. But we heard something else behind the raps and turntable scratches—the sound of a band poised for regular MTV airplay, slick music videos and large arena shows worldwide. It was the sound of a band that would never again play the Ranch Bowl.

Departure and Convergence

Throughout our senior year, Phil and I watched as 311 fandom invaded our high school. 311 logos and alien stickers started appearing on lockers and car windows. Nick Hexum developed a cult-like following among our classmates. Even my seventh-grade brother owned a copy of the blue album.

By the time we graduated in 1996, I’d turned into quite the snarky music critic, and I decided that 311 had become too mainstream for me. Their growing popularity, which I’d championed just a few years earlier, suddenly made them seem unappealing and boring.

My split from 311 wasn’t the only one I dealt with that summer. Not long after graduation, Phil and I broke up, too. Skateboarding, parties and nights with his bros suddenly became more important than me, and I hated it. That summer marked the end of love—a shared special thing I’d cherished more than anything else and felt defined who I was and why I mattered.

photo by Adam Raspler

To heal my broken heart, I turned to music: not capital-M Music, but lower-case. It became one of the first times I began listening to bands because I wanted to hear them, not because of a boyfriend’s influence or a marker of coolness they represented. That summer some friends formed a reggae band that played around town, and I started listening to punk and ska. I discovered that I really liked Joe Strummer.

I’ve read that Nick Hexum cites the Clash as a major influence. I like knowing that we have this in common. While I don’t think that 311 alone directed me to the Clash, I do find it curious how music seems to circulate in some sort of cosmic orb around us.

Music that mattered so much in the past doesn’t anymore, or at least not in the same, conscious way. Yet it’s still—always—a part of us. In preparation for this essay, I dug out my copy of Unity (yes, I still have it) and queued up a bunch of 311 albums to stream online. Why is it that I can’t remember how to do fractions or the names of the countries in South America but, when prompted by a couple catchy opening guitar riffs, the lyrics to all of the songs on Music instantly come to life?

Songs, like memories, fade. But give them a little nudge and they’re back in no time, bringing with them the meaning they once held, inviting us to reflect on familiar places and times that are now distant and untouchable. I feel fortunate for those moments of convergence, when music, meaning and memory align. Sometimes they set us on a new course of understanding—challenging us to ask questions of ourselves, our pasts and our present conditions. Other times, they just, well, feel so good—like having an opportunity to sit down with an old friend as if time hasn’t passed at all.

And, before you know it, you’re 16 again, in your car in the high school parking lot with your teenage soul mate, singing your heart out to something that mattered so much if only for a brief moment in time.