courtesy photos

[Editor’s note: Liner Notes chronicles how Chelsea Schlievert Yates discovered music through the ’80s and ’90s while growing up in Norfolk, Neb. We hope to post a new installment every other week. Read more here.]

by Chelsea Schlievert Yates

I took French class from my freshman through senior years of high school. To this day, I can’t help but associate two guys with those years of language lessons: bassist Mike Watt and my friend Wade.

As a teenager, I was attracted to French class for similar reasons that I was attracted to rock ‘n’ roll: style and attitude. I loved the idea of being hip to the language and ways of such a fashionable, effortlessly cool culture — one of which I hoped to see myself a part one day. But I’m not sure I ever really wanted to put the energy into learning it; I just wanted to be a part of it.

That was also my adolescent outlook on music: I desperately wanted to be in a band, to have that cool rock ‘n’ roll look, but I never really cared about learning to sing or play an instrument. I took piano lessons but didn’t practice nearly as much as I should have, and when I was 15, my dad bought me an electric guitar because he had overheard me mention that I wanted to play one (note: I did not say I wanted to learn how to play one). As I’ve written about elsewhere, that experience was a major challenge for me, and I sold the guitar the first chance I got.

One would think that my unsuccessful guitar venture would have ended my dreams of becoming a rock star. But even as I packed up my Carvin for the buyer, I’d already moved on to my next rock ‘n’ roll daydream: me, the sole girl member of a kick-ass rock band, decked out in leather and leopard print, absolutely rocking it on stage with a powder-puff pink bass. I had no idea how to play bass and, like the guitar, didn’t really care to learn, but I loved the way it looked in my mind.

I was equally as infatuated with the idea of me wearing a striped boatneck T-shirt, biking around the bustling streets of Paris, with a baguette in my bicycle basket, looking like a model straight out of a perfume advertisement. Like rock music, French class offered me a space to imagine a world bigger and different and far beyond the Norfolk’s city limits, with modes of style and expression I felt I’d never find in Nebraska. I was certain that, if given the chance, I could prove myself a loyal citizen to both the worlds of French culture and rock ‘n’ roll.

By the time I started French class in 1992, I was completely in love with Eddie Vedder. Rather than learn vocabulary words or practice verb tenses, I spent most of my time in class either attempting to decipher the lyrics to Pearl Jam’s “Jeremy” or daydreaming about Eddie. My favorite fantasy was the one in which Eddie and I were happily married newlyweds dividing our time between Paris and Seattle. Occasionally, I would situate us in a limousine on the quiet Nebraska highway traveling from Omaha to Norfolk, just off an airplane and on our way to spend the holidays with my friends and family back home. I liked to imagine what Christmas dinner would be like with Eddie at our table.

To my dismay, junior high French class didn’t come close to the ideals of style and elegance that I had associated with French culture. As a whole, our class was more excited about buying Toblerone candy bars (available for sale by the French Club) and learning French swear words than it was about figuring out how to have actual conversations. A kid with a glass eye briefly joined the class; for our lunch money, he would remove it and roll it around on his desk. After a few weeks, during which I’m sure he made a good chunk of cash, he left. I never found out if he dropped or was kicked out.

Shortly thereafter, I became friends with Wade, a quirky kid who sat behind me in class. Wade loved Nirvana. My infatuation with Eddie Vedder paled in comparison to his admiration of Kurt Cobain. Wade and I took French together for the next three years. Our sophomore year, when we were given French names (mine was “Cécile” because there was no French translation for “Chelsea”), Wade insisted on being called “Le Pamplemousse” (translation: “grapefruit”), which he changed mid-semester to “Zut” (translation: “damn it!”) because he liked the way it sounded.

We learned about prepositions, pronouns, articles and irregular verbs. We convinced the instructor to let the class watch The Simpsons episode when Bart goes to France as an exchange student but instead becomes an overworked and underfed child laborer at a vineyard. For an assignment in which we had to create and present a conversation in French to the class, for which most of the students created simple role-play scenarios, Wade and I decided to make a movie. We borrowed his brother’s camcorder and created a film that we titled simply Godzilla Attaque Paris. It starred a giant plastic Godzilla toy, Wade’s GI Joes from when he was little and some Little People I had dug out of the basement at home. Painted on the back wall of our classroom was a giant mural of the Paris cityscape; it worked nicely as a backdrop for our set. I believe we received an A+ for originality and a C- for our use of French. (Our dialogue consisted mostly of monster roars and screams.)

Wade was crushed — as most kids our age were — when Kurt Cobain died in the spring of 1994. Shortly after his death, Wade drew a picture of him. He titled it simply “Mon Hero.” Our French teacher hung it by the classroom door, where it remained for the rest of the year.

At some point, I decided that I was tired of living my cool, stylish rock ‘n’ roll life in my dreams; I wanted to take action. But I still didn’t know how to play and didn’t care to learn an instrument. Someone had told me that out of all of the instruments in a rock band, the bass was the least complicated. I clung to this notion. Finally, I had found an easy way “in” to the world of rock music! I decided that I would be a bassist, but not just any bassist. I would be the super-cool-looking but soft-spoken bass player who intrigued the masses. I wouldn’t say much in interviews, and my musical abilities might be lacking when compared to those of my band mates, but none of that would matter. I’d have the look and the attitude, our fans would be drawn to my mysteriousness, and in terms of fashion and coolness, I would kill it.

Wade played bass, and I thought for sure he’d like my idea. I couldn’t wait to get to class to tell him. I was certain that he’d support me and probably even offer to show me a few tricks to help me pass.

I made two mistakes sharing my plan with him: 1) I referred to the bass as “easy” and “secondary to pretty much everything else that’s going on onstage” and 2) rather than expressing my excitement in becoming a musician or performer, I launched into a speech on how awesome I would look as a rock star.

His reaction bummed me out: “You’d hide behind your bandmates like that, expecting them to carry you even though you wouldn’t really try to play that well? That’s low.” That hurt, but what he said next totally stung. “I think I know what’s going on here, Chelsea. You don’t really want to learn the bass; you just want to look cool.” The way he said it was so accusing, and even though he was completely right, I went on the defensive. No, I told him, it wasn’t about a look; it was about the music. “Fine,” he challenged me, “Get yourself a bass and start learning how to play it.”

I decided not to talk to Wade for a while after that. He had seen through my plan and had called me out, and I was embarrassed. I read chapters of Le Petit Prince without him, wishing desperately that I could be on asteroid B-612 instead of sitting in French class mad at my friend.

Wade broke our silent barrier one day by tapping me on the shoulder. “You know,” he said, “if you’re serious about playing bass in a rock band, you might want to start listening to some bass players — like Les Claypool, Flea, and Mike Watt.”

Since, at the time, I found the Primus too immature for my discerning teenage taste and the Red Hot Chili Peppers too mainstream due to their 1992 hit “Under the Bridge,” I decided to start with Mike Watt, who was — conveniently enough — playing an all-ages show at Knickerbockers in Lincoln. Wade said we had to go. I had no idea who Mike Watt was or what he sounded like, but I said OK.

Wade provided a bit of context about Mike Watt on the way. He introduced me to the Minutemen and fIREHOSE. He told me about D. Boon’s tragic early death. As we listened to Ball Hog or Tugboat?, the album that Watt released in 1995, I was surprised to find out that Watt was the bassist who everyone I loved wanted to play with: Ad-Rock and Mike D, Dave Grohl and Krist Novoselic, J Mascis, Thurston Moore, even my future husband Eddie Vedder.

I was getting excited and couldn’t wait to see what Watt looked like onstage. At first I imagined him to be lanky and cool like Thurston Moore or Iggy Pop, but then harder and more brooding, like Chris Cornell. Perhaps he’d wear a black leather jacket and have lots of tattoos. Maybe he’d have that Keith Richards road-weary look, or be ripped and intense like Henry Rollins…

In terms of appearance, Watt did not live up to my expectations when he took the stage that night. For starters, the dude looked old; he had graying hair, a gut and a burly beard (this was before beards had made their way back to being cool again). The flannel shirt he wore was more Creedence Clearwater Revival than Nirvana. Were it not for the Chuck Taylors on his feet, I would have more easily placed him at the local TH Café that my friends and I frequented on the weekends for cheap coffee, pie and smokes than onstage at a punk show.

But then he strapped on his bass.

And oh my God.

Never has my mind been blown simply by watching someone play an instrument like it was then. I’d never thought about instruments as having voices until that night, never thought about the bass as something more than support for the rest of a band. Watt’s warm, raspy vocals — which sounded like a sore throat coated with honey — just chimed in every now and again to complement the bass, and I was amazed. This was a performance that didn’t center around a lead singer. No way, Watt’s bass was the headliner for this show, and my ideas about what instruments and musicians could and should do were as mixed up in my mind as French verb conjugations.

My eyes tried desperately to keep up with Watt’s hands as they flew around the neck of his bass. My ears attempted to make sense of the sounds I was hearing. Watt seemed to become one with his fans who were losing themselves in the music, their eyes, like mine, transfixed on his bass. I remember one guy who kept throwing himself at the stage, screaming, “PLAY IT, WATT,” as if egging Watt on to play faster, to bend the strings more aggressively, to create more alien sounds. It fed the monstrous beauty of Watt’s bass guitar; with every shout, every fist raised into the air, the bass grew louder, faster, more dynamic.

Watt, this guy who looked like a trucker but bestowed music upon us like some sort of rock god, taught me a number of lessons about music that night. First, there were no such things as “secondary instruments” — any instrument could be the star of the show. Second, though fashion and a “look” can all be incredible modes of self-expression, when it came to music, they didn’t matter near as much as talent, voice and skill.

Third, after seeing Mike Watt, I reconsidered my plan to be a bass player. Though I fell in love with the complexity of the bass that night, I realized that I would never be a bassist. I didn’t want to play; I’d just wanted to play a part. Once I came clean with myself, I felt a lot better and a lot less like a poser. And through that awareness, I found myself wanting to learn more. My conversations with Wade about music in general and bass playing in particular became much richer after that.

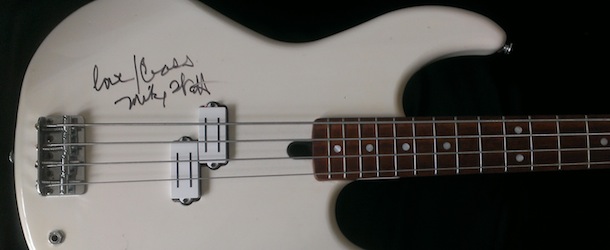

About 12 years later, I met up with Mike Watt again. My husband, Nick, and I were renting an apartment in Houston, Texas, in a building around the corner from a bar where Watt played one night. He’d parked his van right outside our place. Once we recognized him getting gear out of the back, I grabbed the bass that Nick owned and a Sharpie and ran outside. “Hey, Mike Watt,” I said, “Will you sign our bass?”

I wish I could’ve let him know how he’d majorly changed the way I hear music, how I’d been introduced to him in high school French class of all places, and how I played his punk rock opera Contemplating the Engine Room on days that I especially missed my dad, who had died a few years earlier. Watt was polite but in a hurry, so as he signed it I simply thanked him, both for the autograph and for making music. He smiled warmly, handed the bass back to me, grabbed his gear and headed toward the venue. As he walked away, I looked down at his inscription.

He’d signed his name with a tagline that simply read, “love bass.”

And thanks to guys like Mike Watt and my friend Wade, I always will. I may have never become Chelsea Vedder or a super-cool rock n’ roll bassist, but I had figured out a much more important “in road” into music appreciation for myself. And upon the few occasions I’ve been in Paris and have realized I’d forgotten my French language skills, no longer knowing how to ask for directions to the bathroom or even order a croissant, I’ve just had to stop, smile, and reflect on the valuable lessons about myself and music that I picked up in French class instead.

Chelsea Schlievert Yates is a Hear Nebraska contributor. She grew up in northeast Nebraska and now lives in Seattle, Washington. Reach her at cdschlievert@gmail.com.