“When I’ve got the music, I got a place to go” – “Radio,” Rancid

One of the last times I saw my dad, he gave me his old record player. I was visiting my parents at their home in Norfolk, Neb. — where I grew up — and I mentioned that I had been looking to buy one. Dad unexpectedly told me that I could have his since he never used it anymore. With it came the offer to take any of his old albums that I wanted.

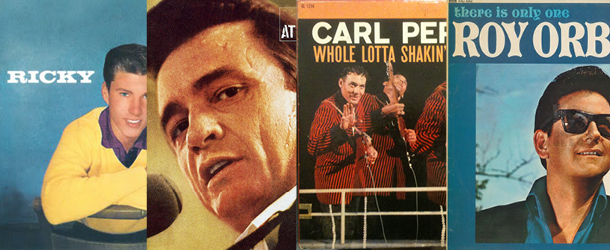

Dad’s records? That wealth of Johnny Cash, early Elvis, Roy Orbison, Buddy Holly and a few early ‘60s teen idols (Ricky Nelson, Dion and a few too many Bobbys to name) who were collected into the mix? All of those old albums I remembered him playing when I was a little kid? (My favorite at age 5 was Gene Vincent’s “Be Bop a Lu-la” — I would beg Dad to play it over and again so I could sing along.) He was just giving them to me?

Had this gift been offered to me in high school, I probably would have rolled my eyes and left the room. During college, I would have thanked him but would not have gone to the effort of lugging a bunch of heavy old vinyl back to the dorms with me. But over the years, my musical tastes broadened, and I had begun to listen to many of the “oldies but goodies,” as Dad would say. Because of this, Dad’s offer became a two-part gift: one, the music itself was something I would forever cherish — to this day, I cannot resist Johnny Cash’s deep, soothing voice, the nervous excitement in Carl Perkins or the hiccups of a young Elvis Presley, especially when accompanied by the scratchiness that only an old record that’s been played far too many times can provide. And two, in many ways, the gift was as if Dad was giving me part of himself mixed in with all of those old albums.

My father and I had never been close. We hardly shared the same views on anything and our conversations were rarely much more than surface at best. It’s not that we didn’t get along; we just didn’t ever talk much. He was appalled that he — a staunch Republican — had somehow produced a “bleeding heart liberal” daughter, and he always seemed slightly terrified by the “this is what a feminist looks like” button I displayed proudly on my backpack. He could never understand why I stopped eating red meat and was even more concerned by the fact that finding a husband, settling down and starting a family were not at all concerns of mine.

When I was little, I acknowledged my dad as “in the know.” He was a smart guy, and whatever he said, I understood as truth. Especially when it came to music. I remember getting really excited on family car trips when Dad would recognize a song on the radio by its first few notes and christen it as, “Oh, GOOD SONG!” The volume of said song promptly would be turned up, and to an 8-year-old me, this signified its coolness.

My dad is responsible for most of my earliest music memories: my first concert (the Beach Boys, on a rotating stage at the Nebraska State Fair, an experience documented by the purchase of an overpriced concert tee that Dad insisted on getting for me, despite the fact that it was four sizes too big); my first cassette player, so that I could listen to the Madonna, Culture Club and Duran Duran mixtape my babysitter made me; a microphone that could sync with our home stereo so that my little sister and I could sing along to Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen and Billy Idol while we danced around the living room, jumping on and off the sofa, living every second of the songs to the best of our 5- and 8-year-old abilities.

I have faint memories of, upon rare occasion, watching my parents dancing in the living room, a safe swing step that could be done without bumping into the coffee table or knocking things off the bookcase. My sister and I would watch from the sidelines, waiting in anticipation for the song to end so that we could cut in and have Dad swing us around the living room dance floor.

During my teenage years, my father’s musical expertise lost much of its impact on me. These were my days of Juliana Hatfield and Sonic Youth, when The Lemonheads meant more than movie theater candy, and my girlfriends and I shared the dream of sneaking aboard Pearl Jam’s tour bus and pledging our undying love to Eddie Vedder. I reserved my Sunday nights for Matt Pinfield and 120 Minutes on MTV, and Kurt Cobain was yet to become immortalized through his early death.

For my 15th birthday, I received an acoustic guitar. Dad had overheard me mention to a friend that I thought it would be cool to play. What I had meant was that it would be cool to play if I could sound like J Mascis upon picking up the instrument; having to learn the basics, practice and take lessons was not cool. As much as I thought I wanted to be in a band, I had no interest in learning the guitar. But Dad insisted on lessons and faithfully drove me to them every week. It wasn’t long after I started them that my guitar teacher pointed out that my birthday present was too small for me and that I should think about investing in a better guitar. When I mentioned this to Dad (thinking it meant an end to the lessons and a way out of tedious practicing), he immediately began scouring the want ads. Two weeks later, I ended up with a 1973 Carvin in mint condition, purchased from a guy who had bought it new 20 years before and who treated it like it was a favorite child or a beloved pet. He and my dad hit it off, and he threw in a high-powered stack-set amp and speaker cabinet of about the same age and quality for free. And with enough power and gear to play a small arena, I reluctantly went electric.

I muddled through guitar lessons for about a year. My teacher would try to get me excited to play my beautiful new instrument by teaching me songs from Radiohead’s Pablo Honey. But the guitar and I just didn’t get along. I got frustrated easily; I wanted to play but was intimidated by its power. Needless to say, the day that a classmate asked me if I’d ever consider selling my guitar, I said yes. He paid cash and took everything — the amp, the cables, the speaker, the guitar. I was free of being tied to the instrument I couldn’t play, free of having to practice, free of the weekly lessons. But I would never be free of the incredible guilt I experienced upon seeing my dad’s face after breaking the news to him that I’d sold it. We didn’t talk much about the guitar after that.

***

Through grunge, punk, skate and ska, my own musical journey commenced. Most of my nights during high school were spent in friends’ basements that doubled as practice spaces for bands or at a small venue called the Music Box Mansion that hosted local bands and allowed underage kids to hang out, drink soda, perform on stage and escape the painfulness of our teenage years for a few hours at a time. My interest in music grew through college. I attended bigger and at times more aggressive shows, helped a deejay friend with his hip-hop program on the college radio station, and scoured the bins of CD shops with my friends for any NOFX, Swingin’ Utters or Social Distortion discs we didn’t already own.

I developed a stream of rock ‘n’ roll infatuations. My high school crush on Beastie Boy Ad-Rock was replaced by a full-blown obsession with Mike Ness. I loved his look, his gruff voice, his tattoos. I even dated a guy who dressed and tried to live life like we thought Mike did; he was silly and dangerous, and — in true rock ‘n’ roll fashion — he broke my heart. My obsession with Mike was snuffed not long after, and I moved on to Joe Strummer, David Bowie and Patti Smith. I discovered a rock ‘n’ roll father figure in Dave Alvin. His deep voice soothed me through breakups and rough patches. I bought Any Rough Times are Now Behind You, a book of poetry he published in 1996, the title of which came from a fortune cookie he opened upon finishing a meal of Chinese takeout after ending a long-term relationship. Needless to say, the day that — after eating fast-food Chinese with a friend — I opened my cookie to discover the same fortune as Dave’s, I took it as a sign that we were connected by fate. I shared this news with Dave once in Kansas City; backstage, after one of his shows at the now-closed Grand Emporium, I asked him to sign my copy of his book and showed him my fortune that I had taped to the inside cover. Expecting him to reinforce my assumption that the rock gods had united us, I was a little crushed when he only laughed sweetly, winked at me and replied, “Well, now I don’t feel so special anymore.”

Around this time, I met a guy who came from a cool punk rock background that criss-crossed with the old rockabilly music of the 1950s. He dressed like a greaser, had awesome tattoos, smoked too many cigarettes, played the guitar and worshipped Elvis. I’ll never forget the night that he confessed to me, “Sometimes the only time I know there’s a God is when I’m listening to music.” I was in love. Hanging out with him, I suddenly found myself searching music stores for old Wanda Jackson and Carl Perkins discs, alongside the Clash and X. Though my crush started to fade once I found out he lived with his girlfriend and had no plans on breaking up with her or moving out, my love for early rock ‘n’ roll and old country grew.

That spring I graduated from college. According to my dad, I was on my way into “the real world,” my first step being to buy a new car. Although he didn’t really need to be there, Dad insisted on going with me to license and register it. Driving with my father always made me incredibly nervous — no matter where we were or how old I was, I was always 15 and practicing on a learner’s permit with Dad in the car. That day was no different. I made a point to hide my cigarettes and turned the stereo volume down so as not to get scolded by my father on the way to the DMV. Dad didn’t say much during the car ride. I had Mike Ness’s Under the Influences CD in the car — the one on which he pays tribute to the musicians of the 1950s and ‘60s from whom he drew inspiration. Dad recognized a bunch of the songs, many of which he had not heard in years. He looked at me in disbelief and said, “Who is this and why are you listening to him?”

I first interpreted his comment to be one of disapproval and immediately told him we could play a different CD. I reached for the stack I kept in my car. He took it from me (“Hands on the wheel,” he reminded me), and in my rearview mirror I watched as he nodded in approval at a Johnny Cash disc and an old Sun Records compilation.

What emerged was an unexpected moment of bonding — with both of us surprised to realize that we shared certain musical tastes. We ended up talking about ‘50s music for the rest of that drive. I think he was impressed that I knew a lot about it, and I was equally amazed to rediscover my dad’s “coolness.” Suddenly I was 8 years old again on a car trip with my dad, impressed by his musical knowledge and listening, once again, to all of the comments he made. Only this time I was in the driver’s seat; it was my car and my music. I had gained his approval; he had complimented me on my musical selections, and I was beaming inside.

That Christmas a small present found itself hidden under our tree. It was nearly missed during the gift exchange, and at the end, my brother tossed it to me. I thanked him, assuming it was from him. After he said that it wasn’t, my dad spoke up. “Oh, that’s nothing, just a little something I picked up for you. I thought you’d like it.” I remember giving my mom a look of confusion; Dad was never really known to “just pick something up” on his own for anyone.

I unwrapped the present to find Elvis’s young, dreamy face smiling back at me from the cover of the Sun Sessions album. I looked up at my dad, who shrugged and said, “Aw, it’s nothing.”

From then on, whenever I went home for a visit, Dad would casually leave a CD on the kitchen table for me to borrow — something that he had picked up for himself that he thought I would like as well. And prior to Christmas every year, after telling everyone that he didn’t need or want any gifts, he’d call me and say something like, “If you can find a really good Gene Vincent or Jack Scott CD, well, that would make a great present for me.” For some reason, he thought that I had special abilities to locate CDs of rock and pop pioneers and so would always put in a special request at Christmas time. It’s like he would think all year of one he wanted that might be hard to find and then pass along the “challenge” to me. I would always tell him that he could find them himself online, but he never would do so. I think he liked giving me those special missions.

Then he gave me his record player. And all of those wonderful albums. He went to bed early the night I started going through them, deciding which to pack and take with me. I took as many as would fit into my crate. I would have liked for him to have been awake as I made my selections so that I could’ve asked him questions and talked to him about the music, but maybe there was a reason he wasn’t.

***

On June 7, 2008, Dad had a stroke. It was a severe one, targeting the left parietal and frontal lobes of his brain. The part of his brain that controlled motor skills, speech production and language comprehension. We spent the following week in the hospital with him, sponging his skin with cool water when it felt hot to the touch, covering him with extra blankets when he felt cold. We read to him and spoke to him, though none of us were sure how much of it, if any, he could hear or understand. We stayed by his bedside, slept sitting up in the uncomfortable chairs of the ICU, so as not to miss any signs of improvement.

They did not come, and six days later — on Father’s Day, actually — we left the hospital without him. We endured the stream of visitors armed with sweet rolls who showed up at the door to express their sympathy. We managed to select an urn as well as appropriate funeral attire. We made it through the service and slowly began to attempt life without him, figuring out how to live with the variable feelings of emptiness that had surfaced in his place.

His record player collected dust in my apartment for a long time, just like it had in his house. One day, after being exhausted of feeling sad, of thinking about the ways in which he wasn’t with us, what he was missing, how we were missing him, I tried instead to acknowledge the ways in which he was still present. I dug out the records. Once the needle awakened the scratchiness of an old Dion album, I was instantly that little 5-year-old again, dancing around the living room with her daddy, driving in the car with him as he shouted, “Oh, GOOD SONG,” turned up the volume and started keeping time by beating his thumbs on the steering wheel.

***

Last year my fiancé Nick and I moved to Seattle. My dad’s albums now live at home on the shelf next to Nick’s. It’s a funny contrast, Dad’s worn-out, frayed-edge copies next to the vinyl Nick collected from his college days — most in pristine condition, safely stored in their plastic slips. We decided to replace the old record player (which had finally worn through its last belt) with a new one. Settling in to our new neighborhood, we also discovered a record store down the street. And we made a pact: Anytime we walked by, we would thumb through the store’s clearance bin and each pick up an album to grow our little mash-up collection. I find myself buying albums that seem like they should be in my dad’s collection, those that fill in some of the gaps. One of my friends recently told me that I buy records like a 65-year-old man. In a way, I guess that’s true.

For Christmas this year, Nick gave me a ukulele. Since losing Dad, Christmases especially are rough. I miss my Christmas present music challenges terribly, no longer having a reason to order digitally-remastered CDs from Amazon.com with slick-haired young men on their covers. But the little Christmas ukulele was momentous. Age 34 and I’ve finally found an instrument that I can strum without fear. I sometimes even sing when I play, much to the dismay of my neighbors, I am sure. I like to put on the old albums — which are now a mixture of mine and Nick’s and my dad’s — and play along when I can: Johnny Cash, the Everly Brothers, David Bowie, Elvis, T-Rex, Merle Haggard, Patsy Cline, the Ramones. The uke may not be as cool as an electric guitar, but I have fun with it. And I like to think that somewhere — wherever he is — my dad is looking upon me, with that smile that says, simply, I’m proud of you, kid.

Chelsea Schlievert Yates is a Hear Nebraska contributor. She grew up in northeast Nebraska and now lives in Seattle, Washington. Reach her at cdschlievert@gmail.com.