There is a crooked yellow house at 920 D St. in Lincoln.

The steps to the porch crack and crumble. The porch slouches lazily to one side. The high peaks of the roof over attic windows give the impression of a house taller than it’s supposed to be. Built in 1886 by Albert Watkins for his family, it looks like it could serve as the home of a Tim Burton character in some darkly animated children’s film.

But the house, affectionately named Colonel Mustard by the theater company that calls it home, is far from a solitary haunt ripe for urban legends and ghost stories. Since 2007, it’s been the operational center for Colonel Mustard Theatre Company, an amateur arts collaborative that produces original plays and musicals both in the house and around the Near South neighborhood in which it sits.

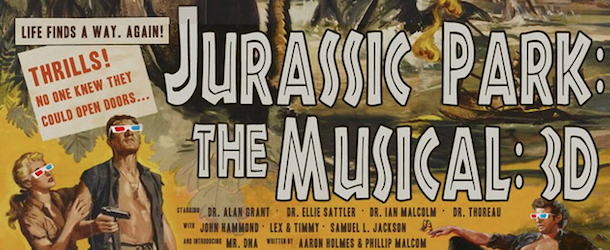

Tonight and Saturday, Colonel Mustard premieres its latest project, Jurassic Park the Musical: 3D, at 7:30 p.m. in a vacant lot at the intersection of 9th and D streets, a half-block west of Colonel Mustard.

At first, the idea took the form of just attic plays for house parties — short pieces written and performed by and for a group of friends. In 2009, though, while working on another attic play, a Jurassic Park spinoff, Aaron Holmes said he realized their project had potential to be much bigger than the small attic.

So the troupe came up with Jurassic Park the Musical, Colonel Mustard’s first outdoor musical. On performance night, more than 200 people filled the house’s backyard to watch a group of young people, most with little theatrical experience, put on a comically cheap production of the first musical members of the theater company had ever written.

While their musicals have expanded in size and vision since, Colonel Mustard is not concerned with superior production value. They’re more concerned with trying things they haven’t before.

“I have a pretty good understanding of the sort of stuff that people have access to in Nebraska — the sort of stuff you would see at the Lied on a touring national show or the stuff at Pinewood Bowl or a local high school,” Holmes says. “And in contrast to those things, we’re trying to create something that is completely homegrown.”

This week, in preparation for JPTM3D, the Colonel Mustard house has been stirring with activity. Two girls in the dining room have prepared puppets and costumes. Another girl in the backyard has spray painted cardboard cutouts of cartoonish dinosaurs. Cast and crew have worked through the afternoon on the set and have gone straight to dress rehearsals.

Aaron Chambers, a veteran member of the company, is just meeting some of these people for the first time today. He says its not uncommon that people will have heard about what they’re doing or maybe have seen one show, and show up to the house looking to help out. There is always work to do, so they’re never turned away. He encourages set designers to be creative, and to go with their instincts, even if results might be considered substandard.

“In the end, it’s more important that people feel like they’ve contributed than that the show come off as professional.”

This year, preparation has meant anything from constructing felt and chicken wire into the shape of Triceratops poop to finding ways to make their yearly musical match the previous one in creativity and scope. And they’ll do it all with a volunteer crew and a budget that might pay for the food in John Malkovich’s dressing room.

The latter task presents a particularly difficult challenge this year as Colonel Mustard follows up last summer’s Gods of the Prairie, an ambitious, choose-your-own-adventure kind of play that spanned several locations and 10 blocks around the Near South neighborhood in Lincoln. For Gods, they gave maps to audience members to tell them where scenes would take place and turned the west side of the state capitol building into a sort of Mount Olympus of the plains.

Unlike last summer, there will be no shuttling an orchestra from scene to scene, or hoping audience members make it on time to each act. Still, Aaron Chambers says JPTM3D is an equally refreshing alternative to traditional theater houses.

“I kind of didn’t think we could think of anything more creative than Gods of the Prairie, but this is creative and new in a different way.”

“Basically, we’re building a huge wall in this ring, that becomes the enclosure that the audience goes into,” says Holmes, who co-wrote the script. “The structure of this play is different than almost any theater that’s ever been done.”

Scenes will take place in and around the top of the ring, giving the audience a 360-degree stage to watch. Holmes says the “3D” in the musical’s title originally functioned as a tongue-in-cheek reference to the Hollywood trend of re-releasing popular films into theaters. The title seems especially appropriate considering Colonel Mustard’s previous performance of Jurassic Park the Musical. Holmes says they won’t be performing the same script from 2009.

He said Jurassic Park had a huge impact as him on a child. Now that he and other Mustard members, like Philip Malcom who wrote the music for both versions, have had more experience with musicals, they wanted to give the concept a second shot with new music and a new script.

And yes, live theater already exists in three dimensions, Holmes realizes. Still, the company looked for a way to make JPTM3D as three-dimensional as they could. In doing so, they created for themselves a new way to perform.

“Even though putting it 360 degrees around the audience doesn’t make it any more three-dimensional, it kind of feels like that’s how our play is in 3D,” Holmes says. “It can be close to you and far from you and on any side of you. That’s the way we’ve turned it into 3D theater.”

Even if Colonel Mustard is breaking ground in theater format, the company doesn’t expect, or strive for, professional production. Chambers, who stresses the importance of cast and crew having fun and being involved over perfection, says their production has been described as “endearing.”

“It speaks to the spirit of the people of Lincoln that they accept and even applaud less than perfect things,” he says. “It takes a keener eye to see beauty in Nebraska in general. I guess you can see a parallel there: between people that just want to have fun doing this cantankerous theater production, and people that see that as a positive and beautiful thing to support.”

With a few locational exceptions for Gods of the Prairie, their summer musicals have taken place in backyards or vacant lots. This year’s venue sits along 9th Street, a major arterial road for west Lincoln. For Colonel Mustard, incidental noise and outside factors are part of what they do.

“We know we’re in a public space, and we’re interacting with a very public space,” says Chambers, who plays two characters and a few dinosaurs in JPTM3D.

Sometimes that means repeating lines that were drowned out by honking, or shouting to be heard by fellow cast members. One year, the Lincoln Saltdogs hosted a fireworks show on the night of the musical, which was visible from the vacant lot.

“To have the community be alive right next to us in the form of cars that make noise as they drive by is a beautiful, frustrating thing.” Chambers says. “It’d be silly to pretend it’s not there.”

For Holmes, too, Colonel Mustard’s approach to performance is often about not ignoring the obvious. He recalls seeing the musical Les Miserables several years ago in London, which he remembers as a massive show with high production value and a deeply intricate and realistic set, a stark contrast to Colonel Mustard’s handmade, low budget sets.

“It’s cool that they have the time and resources to put something like that together,” he says,” but what I think is really magical about theater is when, instead of actually having something that looks like a gun or a car or a dinosaur on a stage, you put something on stage that clearly is not that thing.”

For example, Holmes says they had a giant rattlesnake monster in Gods of the Prairie, made with a snake-like paper mache head on a wheelbarrow, followed by hula hoops strung together. A crewmember on roller blades held the end, shaking milk jugs filled with coins to imitate the snake’s rattle. He describes it now as “the silliest thing ever.” Although he wrote the rattlesnake scene, he says that, with lighting, music and acting, there was something “legitimately kind of scary about it.”

“In theater, you can put something on stage that looks nothing like a real dinosaur, and you can sell it through the way that the actors or puppeteers move their bodies, and through the way you light it or actors react to it.”

Holmes says he enjoys the dual realities that theater can inhabit: the physical reality in which the audience knows they are not seeing a real dinosaur, for instance; and the imaginative reality, where the audience let themselves believe they are seeing a real dinosaur.

An honest and open approach to the farcical nature of theater is what excites Holmes about what Colonel Mustard does, he says.

“Theater can’t do realism the way that movies can. And I don’t think it should push toward that.”

Beyond explorations of the avant-garde, Colonel Mustard is a way to engage a community. Chambers views Colonel Mustard musicals as a small way to brighten a neighborhood that doesn’t get much attention.

“It’s community-based, so a lot of people are from this community. It’s bringing life to this area of the city.”

“(Colonel Mustard) exists to make people’s lives a little better, reaching out and saying, ‘Hey, come enjoy this and be entertained,” Holmes says.

The lot on which JPTM3D is staged was once home to the Zion Church before it burned down in 2007. Chambers says the church hosted a lot of programs and did a lot of positive work in the Near South neighborhood, such as food drives and an arts committee aimed at creatively engaging the community.

“I don’t think it’s by accident that some of that spirit continues on this ground.”

Jacob Zlomke is an editorial intern at Hear Nebraska. He recommends bug spray for outdoor theater in August. Reach him at jacobz@hearnebraska.org.