If you’re writing and you want something to be noticed, put it at the beginning.

Notice the primary (likely the only) way in which Günter Voelker thinks author Denis Johnson — the man who first created Jack Hotel — is “full of shit.”

The name of Voelker’s Lincoln bluegrass band Jack Hotel is derived from a minor character in Johnson’s much-lauded 1992 collection Jesus’ Son. They’re stories of drug addiction, violence and seemingly resultant amnesia that are as offhand as they are theatrical, as inseparable as they are textually ignorant of each other. Not unlike the 10 songs on Jack Hotel’s debut LP Good Sons and Daughters, out two weeks ago on Sower Records.

Voelker isn’t buying it when Johnson claims the stories existed previously as bar tales, informal oral yarns, he barely adapted for the page.

“I think it’s way too polished and meticulous and gem-hard for that to even be possible,” Voelker says. “I don’t believe it for a second.”

The people in the stories and the songs, who rove and hurt and stop only to self-medicate and explain, are not Johnson or Voelker, but they have storytelling minds themselves. In part, that’s why the stories exist. Because fictional people seem fit and willing to tell them. The congruence and raised edges of Jack Hotel lyricism leads its daring, impaired (but never dimwitted) narrators to grand metaphors: meth cooks who offer that “the moon is glowing red like the heart of man” or the gas station gunman who imagines a future of lycanthropy for himself in “a fallow field.” But Voelker being the one who put the words in those mouths — probably full of yellowing teeth — is not Americana voodoo. When his songs make their Shakespearean, Denis Johnson-esque turns to the audience, as in “Tobias,” and ask the listeners directly for help or attention, Voelker says he’s been imagining the audience the whole time. Even if it’s startling, even if a wall in the point-of-view is demolished, it’s initially just a device to reach for the songwriter’s toolbox.

“My favorite songwriter interviews are the ones where they’re not romanticizing at all,” Voelker says. “The ones where someone talks about sitting down and dashing out a song in five minutes are infuriating to me.”

Even so, Voelker was given, or wrestled into existence, or tapped into, or furiously built something at the birth of Jack Hotel. He’s the former guitarist for Ember Schrag and his band comprises Josh Rector (fiddle), Joe Salvati (dobro, lap steel) and Marty Steinhausen (upright bass). But who knows if Jack Hotel, much less Good Sons and Daughters, would’ve been possible had Voelker not penned 20 songs in three months.

“I would finish one in a night. Almost all of them. I’ve learned that that’s pretty uncommon.”

One such story is the writing of “Tobias,” which was brewing in Voelker’s head during a late-night run and then fell out of him to the backdrop of a thunderstorm and in the wake of one monumental minor chord. If that sounds like a dramatization of a songwriter’s life, the writer persistently acknowledges the deliberate legwork of resolving chord and rhyme structures even in the midst of a sizzling hot streak. What became Good Sons and Daughters, as well as the other 10 songs cycled in and out of Jack Hotel sets during the past year, came from a beginner’s zeal, the first batch of songs Voelker was willing to live with and to share.

“It’s a certain restless feeling and you always feel on edge. At any given moment — probably at work — I don’t have a guitar [and] I feel stressed out. I’ve heard that described as a ‘state of flow.’ The times I find it stressful is when flow is interrupted by my life. I have to be a friend, to be a husband, be an employee.”

As a live band, Jack Hotel played its first show in February 2013 at Zoo Bar with David Vidal: another songwriter capable of Voelker’s easy, but jagged turns of phrase. At the release show for Good Sons and Daughters on May 23, the songs of dark wit and energy underwent a transformation into unlikely barroom favorites. During “Sideways Lightning Blues,” the crowd filled in a blank after “I wish I had me some sideways lightning shoes” with an athletic vocal burst of “some Nikes!” People belted out the chorus to “Throwing Pennies,” a remembrance (just barely missing bagpipes) of a childhood flame turned forsaken mother — which, like a pink ribbon in a Hawthorne story, stands in more for a comment on lifelong muddying and guilt than just a tale of “Diana.”

As a unit, the band is crisp, sharp and tight: dozens of strings on guitars, basses, dobros, violins and banjos being plucked in streams of rhythm by an Appalachian orchestra.

“They’re very intuitive players, and they’re listening really hard,” Volker says. “I definitely think of Jack Hotel as a band, and never like, ‘Oh, I’m Jack Hotel.’ I’ve always kind of resisted that. I’m not Jack Hotel. I never thought of it like a persona for me to embody.”

photo by Cameron Bruegger, Lincoln Exposed 2014

That night in May, Voelker stood before the crowd with a red rose (another pink ribbon of sorts strapped close to the heart of the writer of such troubled tones) dappling his guitar strap. While the others stood, Salvati sat so low on stage that the volatile sounds of his dobro seemed to rise up from the floor. In that moment, you couldn’t have paid Salvati for a facial expression. He looked like he was trying to cut a piece of perfectly straight wood freehand. Rector flavored songs like “Throwing Pennies” with flailing Celtic-sounding fiddle. Casey Hollingsworth (of Bud Heavy & the High Lifes) played mandolin and notably left the stage to play the Zoo Bar’s house piano on “Tobias,” and while the notes were inaudible, the rumbling atmosphere they produced in the bar may have been the point. And in the short history of Jack Hotel, there are stories of Steinhausen’s musical ear being so innate that at shows he’s tuned Voelker’s guitar pegs mid-song.

Though a few wayward string clangs and intentionally scraping moments on the fiddle create an atmosphere of scuzziness, Good Sons and Daughters is a folk album in, indeed, a traditional American tradition. Unlike Jesus’ Son, there are no moments of sudden and stirring homoeroticism. It’s too crisp for some of the hallucinations of Johnson’s writing, no stories in which that narrator realizes with some kind of half-realism he’s been inside the dream of another character. What the record does do is blend and toil and inspire uncertainty until you’ve no idea whether the narrators are the same or different people. Or can be trusted.

“It kind of is like an album,” Voelker says of Johnson’s book.

* * *

If you’re telling a story full of turmoil and you want something to be noticed, you could gamble and put it in the middle.

But positioned there, it should be a departure, a smooth hand suddenly running ragged over the gear shift. Screeching tires, like those in Johnson’s “Car Crash While Hitchhiking” trying in mechanical fright not to collide with a wall of pitch dark. Something like the grating and wild production of the song Jack Hotel song “Iodine.” Something like a death halfway through a story.

Four women die during Good Sons and Daughters. Three are murdered. Three children have left the world the same way.

“I had never done the death tally,” Voelker says.

“Iodine” is electrified and distorted as a piece of studio experimentation. On an album that, sonically, is mostly the way Jack Hotel would saddle up in your kitchen or on a street corner, Voelker asked Fuse engineer Matty Sanders to manipulate the vocals with distortion until it was “stupid,” and they’d walk backward from there. At a listening party of the Good Sons and Daughters vinyl before the release, between the end of Side A (“Throwing Pennies”) and “Iodine,” some people went outside and smoked. Others took a breather and chatted to reset before Side B, what Voelker hypothetically subtitles “Loners and Drifters.”

“Then people were really in for it,” Voelker recalls the party, laughing. “Your palate is reset and I could come at you with anything.”

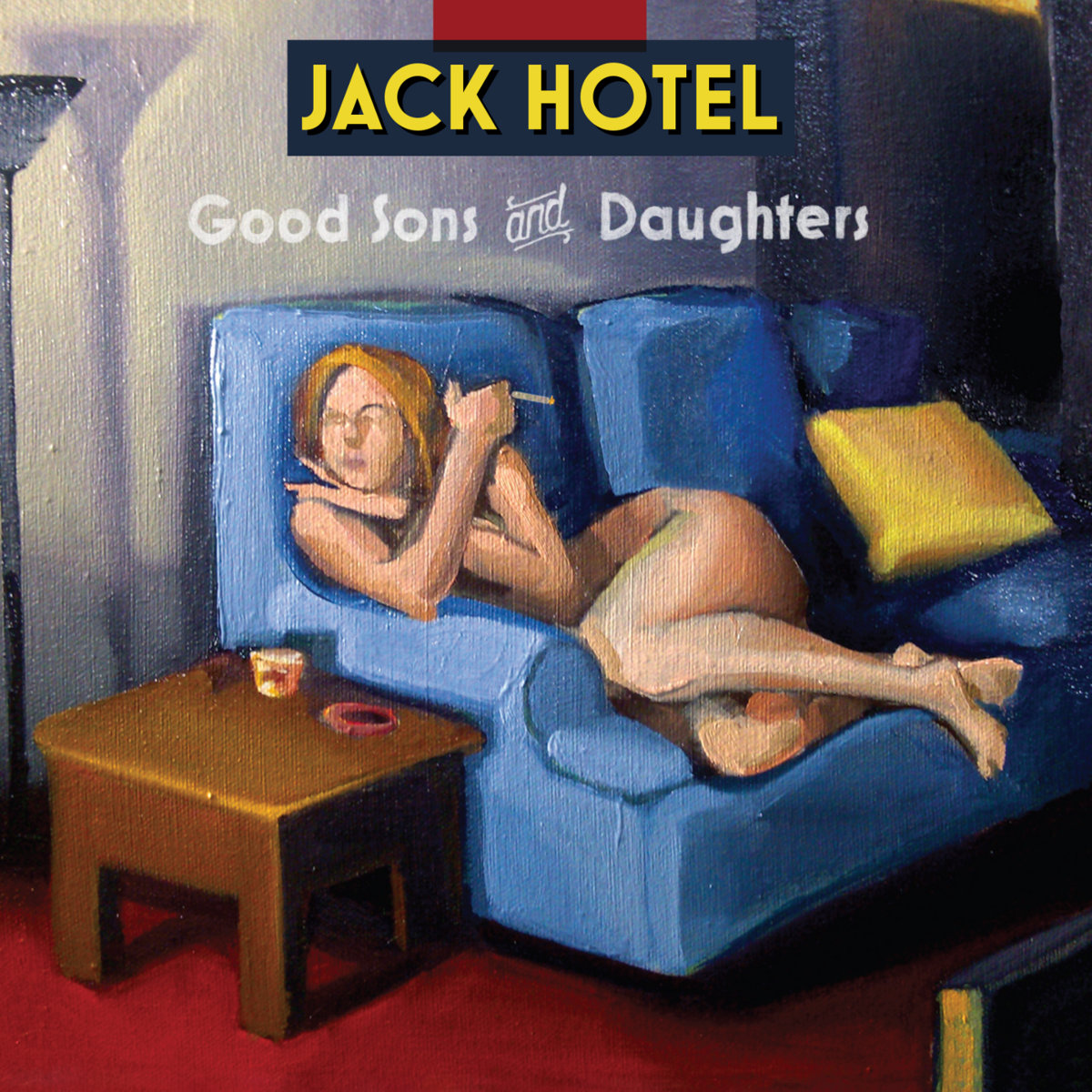

album art by TJ Templeton

As with the meth cook narrator of “Iodine,” Jack Hotel’s is a masculine album. Why so many become violent doesn’t feel like it can be ripped away from the centuries of folk voices in which women have been killed and brutalized by emotionally underdeveloped men. But Voelker says he takes too much care with each character for it to be a parroting of outdated and chauvinistic value systems.

“I’m pretty aware of the folk tradition in which men mindlessly, seemingly, commit murder. Like, she wouldn’t marry me so I grabbed by her hair and threw her in the river, watched her float down and die. It’s really macabre.”

He mentions the New Orleans folk band Hurray for the Riff Raff and the song “The Body Electric,” in which their frontwoman, Alynda Lee Segarra, critiques the murder ballad form, suggesting the future hazard in embracing the universe of the solitary, aggressive man:

Oh, and tell me what’s a man with a rifle in his hand

Gonna do for a world that’s just dying slow?

Tell me what’s a man with a rifle in his hand

Gonna do for his daughter when it’s her turn to go?

photo by Bridget McQuillan, SXSW 2014

“It gave me shivers,” Voelker says of listening to the song of the first time. “I just nodded in agreement with it. I recognize that I have songs in which women are mistreated, but I don’t think it’s particular to women. I just think it’s particular to the characters. But I don’t want the album to be implicated by that. I wouldn’t care for that indictment.”

Rather than the cold gaze that brandishes the gun, Voelker seems more in tune with the sweaty finger on the trigger, the one that might slip and fire no matter what. Where chaos happens and it can’t be taken back. Seven people die on the record, but no bodies are methodically disposed of. There is no illusion that life could remain the same for the person turning and running away.

“That’s probably a lot of where I’m coming from: a series of bad choices. I don’t condone violence against anybody, but in the heat of a really passionate fight, there’s a lot of places you can go. The decorum will leave the room pretty quickly. The worst words you know are hurled around the room. It’s just a hair thread that separates it from going to the next level. Hopefully your better nature prevails.”

* * *

“When you’re arranging and you want to highlight things, you can put them at the beginning, middle or the end,” Günter Voelker says.

The album saves its good daughter for last. The narrator of the final track doesn’t die and doesn’t cheat. “A Better Angel,” with its resolving chords and Joe Salvati harmonica solo, feels hopeful, even if it prescribes no hope for the woman traveling southward toward Durango, running from the-writer-doesn’t-know-what. He could make it up. It could easily be any of the havoc described in the preceding nine songs, but Voelker can’t, in good faith, specify.

“It needed to be separate from the others. I wanted to make a special case of it.”

Good Sons and Daughters comes from a Jack Hotel song of the same name, which does not appear on the album, hinging on the lyric: “Half of the children are good sons and daughters, and I’m a good man half of the time.”

“[The title] made it clear to the listener that they were about to hear from a cast of characters,” Voelker estimates.

Voelker is not a caretaker nor an omniscient father to his characters. But he talks about them easily by name — Molly, Diana, Kathleen — when speculating which one might be smoking in the chair on the album cover (from the painting by TJ Templeton), the slope of her body position signifying both a lounge and a languish. The songwriter holds a psychological closeness to the characters they may not share with anyone in their actual world. It may just be proximity, but there’s an investment in their existence.

“When authors are asked, ‘How did you write from the perspective of a man or a black woman or what gave you the right?’ I’m always kind of annoyed with the question on behalf of the writer. You just do it. Just write them as people. Just start. We’re not so different.”

photo by Rhett Muller

The rigid idea of the “character song,” with an overt narrative quality about a person with their own name, does something to quell curiosity about who is who in the relationship between a song’s world and its writer’s. For his part, Voelker tries to be an observer of humanity, not a voyeur for a certain, struggling demographic of it. It’s at this spot where backstory does its best to be humanistic, not balladic.

“The dividing line is pretty thin between people who are ostensibly normal and people who are obviously desperate. Everything could fall apart for a person. The business where you work shuts down, that’s a big one. Your love life falls apart. It would just be a combination of circumstances for anyone and suddenly they’d look like the desperate one. I’d hate to think that I find desperate characters and exploit them. I’m very careful about it.”

At the conception of “Dead Man’s Run,” away from an instrument and notepad, riding with his wife on a train from Sacramento to Reno, Voelker was just a passenger, annoyed and uncomfortable. If the gabbing of the man he calls “Rudy” was a gift, for instance, he was a present like an old woman screaming at a cashier about correct change or a yuppie swearing into his Bluetooth. Again, without treating writing as a kind of conjuring, the work came after.

“I just remembered things he said [in the train car], and changed them as I saw fit.”

The songs are three minutes long. They are not disaster films nor morality plays nor epic sagas.

“There are stories I’ve read that when I’ve recalled them they’ve had the ring of memory,” Voelker says. “No novel is like that. Short stories could almost be implanted in your mind as false memories. If they’re written well enough.”

Jack Hotel songs rely on a kind of potential energy. The police sirens, suicides and second chances are always bracing themselves somewhere a few seconds after the song has faded from earshot. For the present, Good Sons and Daughters looks around at its children with short-term memory, artistic status reports.

“I don’t know if she makes it,” Voelker says of “A Better Angel” and the woman in the song, “Or if she gets to Durango if that does for her what she hopes it would do. I hope so. I root for her.”

The majority of your life happens in between the moments you would say it does.

Chance Solem-Pfeifer is Hear Nebraska’s managing editor. Reach him at chancesp@hearnebraska.org.