[Editor's note: This feature previews Jack Hotel's appearance on Hear Nebraska FM, this Thursday starting at 6 p.m. on 89.3 KZUM. Stream the show at kzum.org. See Jack Hotel tonight at Meadowlark Cafe, and see the band's Günter Voelker at The Zoo Bar's Troubador Tuesday on Sept. 17.]

by Günter Voelker, Jack Hotel

My wife and I were on our first cross-country train ride, heading home from Portland, when we picked up the narrator of my song, “Dead Man’s Run.”

He boarded in Sacramento, and we lived with him for a few hours as we made our way to Reno. He was short, past middle age, wearing a ratty T-shirt (it might have been a "Big Johnson") and a gray mustache. He had a cooler full of contraband beers, which he handed out in gregarious fashion while he regaled the full car with his history, his plans and his dietary preferences.

He had been to jail. He was supposed to meet his girlfriend in Reno. She was going to give him a cheeseburger. He loved cheeseburgers. Did we know that it was his birthday?

Much to the aggravation of any passengers trying to rest (it was early, and you find sleep in coach whenever you can), there was a contingent of equally loud Mississippians aboard who found him delightful, partook happily of his beer and prompted him frequently to continue.

He was seated next to a taller guy about the same age. More than anything, the two reminded me of Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare’s characters from the movie Fargo. At one point, the shorter one (our friend) paused to ask his seatmate, "So, do you want to hear my story?" To which the seatmate responded, "No."

I have often thought about those two since, and have written a couple songs featuring one or both of them, obliquely.

In "Dead Man's Run," the narrator's 50th birthday takes place aboard the Texas Eagle, which is an Amtrak train, but not the one my wife and I took. I invented two children for him, a son and daughter. I never named him, but if pressed, I would call him Rudy.

Rudy tells us that he killed his son, but offers no details. I imagine it happened during an argument. Whatever the specifics, Rudy served a sentence in Huntsville Unit, during which time his daughter moved to Michigan. Now he has made his way to Lincoln, possibly on his way to see her, and finds himself stranded, homeless and living under a bridge.

As a songwriter, considering the musical tastes of a first-person narrator who isn't me raises the question of whether he is a singer. Does he play guitar? Did he write this song? If he is from Texas, am I supposed to sing the song with an accent?

I’ve never thought about most first-person narratives — especially in music — very literally, unless the story asks me to. In the case of “Dead Man’s Run,” I see the song giving voice to Rudy’s internal monologue, or to thoughts and feelings he might not have been aware he had.

“Dead Man’s Run” never demanded that I figure out Rudy’s birthday, specifically, but it must have been in the early ‘60s. I believe he liked music, and from childhood, artists like George Jones, Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard would have held exalted spots in his personal pantheon, but for a long time I suspect he was an easy-to-please radio listener. In the mid- to late 1980s, he got into heavy metal.

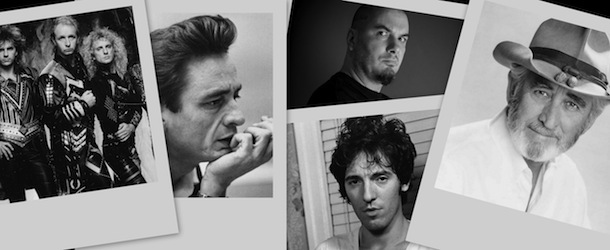

Here are a few cassettes I see kicking around on the floor of his car, when he still had one:

“Thunder Road” by Bruce Springsteen

Of course Rudy had a soft spot for The Boss, and really any music that trades in nostalgia. “Thunder Road,” when he first heard it, made him feel much older than his chronological age. He was 13, and though he didn’t have a girlfriend, and didn’t know who Roy Orbison was, he couldn’t help picturing himself in a car with his own “Mary” — not a beauty, but all right — outrunning his future.

“Tulsa Time” by Don Williams

By the time he actually got his driver’s license, Rudy had already been a father for a year, and now he had a newborn daughter. At night, after his son and girlfriend had gone to bed, the only way to keep his daughter from crying was to drive her. The second he stopped, even for a red light, she would commence sobbing.

The song that seemed to keep her happiest was “Tulsa Time,” sung by Don Williams, popular then on the radio. Rudy bought a copy of Expressions, and for a long time after his daughter had grown out of their late-night drives, he continued to sing the song to her as a lullaby.

“Screaming for Vengeance” by Judas Priest

1985 marked the beginning of Rudy’s obsession with loud music, which, from the fast-hurtling confines of his car, appealed to the part of him that wanted to scream. He was in his early 20s, with two children over the age of 5.

“Cowboys From Hell” by Pantera

The year Rudy went to prison, Pantera’s album Cowboys From Hell was in heavy rotation in his tape deck. With lyrics like, “Showdown, shootout, spread fear within, without / We're gonna take what's ours to have,” he could howl along with vocalist Philip Anselmo and almost convince himself he had control of his own life.

“I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry” by Johnny Cash

In prison, especially in the first year, the songs that affected him the most were ones that reminded him of his own father. Foremost was Johnny Cash’s rendition of “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” a Hank Williams tune he remembered hearing his father sing once, drunk at a party.

It was the first time he had ever thought about his father, a stern disciplinarian, feeling much of anything besides anger. Alone in his cell, in a misty-eyed reverie of self-pity, Rudy listened to this song until the tape wore out, projecting his youthful memory of his father onto his own son, knowing that the depth of his regret would never be understood by the person he wanted to understand it.

Günter Voelker is a Hear Nebraska contributor. Hear his songs live this Thursday on Hear Nebraska FM, starting at 6 p.m. on 89.3 KZUM and streaming at kzum.org. And reach him at gunter.voelker@gmail.com.