As opaque, erudite and narratively dense as Cursive can be, The Good Life could play host to Tim Kasher’s most confounding creations.

On Saturday at The Waiting Room, it was embodied in the young woman in the audience singing every word of Album of the Year — the title track and the handful of other songs played from the 2004 record — into her boyfriend’s ear. And he sang them back. And they shared a moment. Lips brushed past each other.

What’s so confusing about The Good Life is whether this, and much of the other visible joy and romance in the crowd, is the saddest of sad ironies or totally appropriate. Album of the Year and a very significant cut of The Good Life catalogue appear fundamentally based around misunderstandings between lovers. And reflecting on fallout. Sharing a moment of sensual privacy at a sad rock concert is exactly something that would happen to two characters in a Tim Kasher song. So what comes first when considering what fits? The genuine experience of people? Or the knowing literary commentary behind it all?

Welcome back, The Good Life.

Kasher, guitarist Ryan Fox, bassist Stefanie Drootin-Senseney and drummer Roger Lewis played to a packed house for 90+ minutes on Saturday, announcing they’ll be recording a new album in Omaha in the coming weeks, on track for a summer release.

To start at the beginning of the billing, Oquoa’s position on Saturday was an interesting one. As a newish, still-evolving and non-touring band, it clearly benefitted the most, exposure-wise, from being on a billing with Saddle Creek mainstays. Oquoa’s music feels absolutely for the patient and the discerning listener. There’s guitar and New Wave-resonances, sure, but the shifts in Oquoa songs feel like they happen by a different measurement of time, not so much written on chord structure, but the actual single chord changes, the feeling of large, unavoidable movement to a different plane of the song. The unreal time in which the songs unfolded made things like Roger Lewis playing his cymbal with a violin bow transfixing. Frontman Max Holmquist even seemed to banter with the crowd in slow motion about the simultaneously occurring Holiday Bowl.

New songs like “Dreamcatcher” stretched well past the five-minute mark and saw keyboardist Patrick Newbery not as an adornment to the songs (as he might’ve started out upon joining Oquoa earlier this year), but as their center: in the driver’s seat with a climbing synth melody. Holmquist, meanwhile, stroked the guitar strings delicately with just his index finger nail, occasionally cupping the whammy bar for a wash that could feel both constant and completely incidental. All this ambient evidence noted, Holmquist absolutely embraced the big moment in front of the growing crowd, locking his knees and swaying his hips on “Move Your Bodies.” During the strikingly extended vocal holds of “Yellow Flags,” he amplified their oddity by growling, and mangling the delivery just a little.

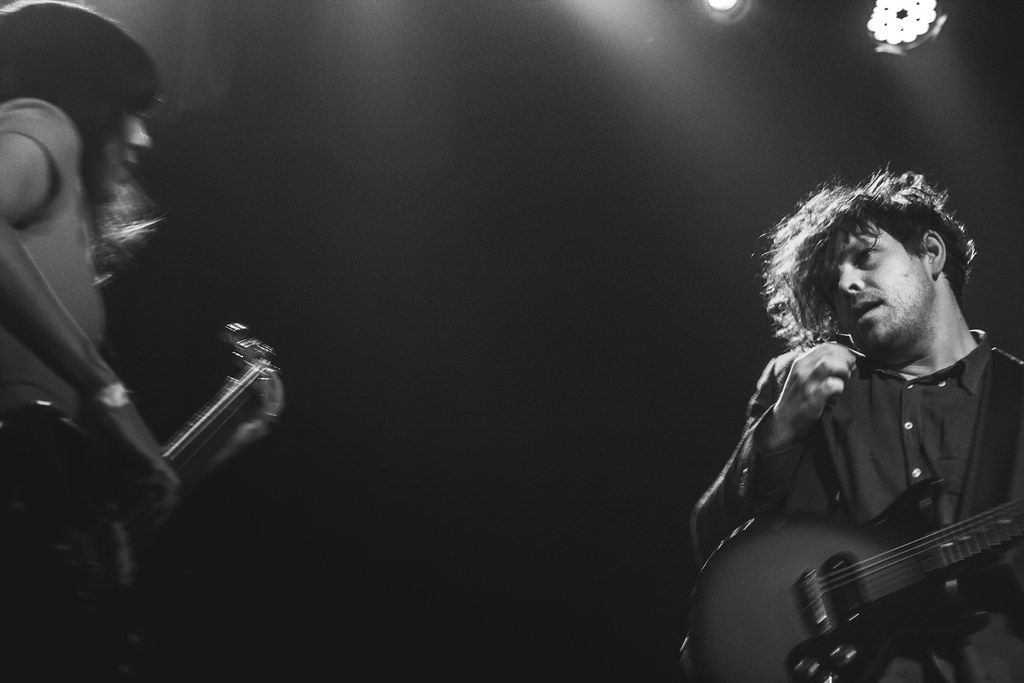

Foreshadowed in this preview from last week, Big Harp essentially rolled out their forthcoming third record for the audience. As with the widening distance between White Hat‘s tasteful traditionalism and Chain Letters’ scuzzy sharpness, the new album sounds all over the place: exactly where the now-trio (with drummer Daniel Ocanto) wants to be. Repeatedly, Big Harp’s new style came off as a hooky strain of tropical punk rock: a product both of Stefanie Drootin-Senseney’s high-string bass playing and the rapid bar-chord strumming of her husband, Chris Senseney. Though it seems very possible that the record they just wrapped with producer John Congleton could be much busier than what we heard on Saturday, the presence of Ocanto opens up possibilities for the husband-wife duo to do even more musically, with movement as an absolute constant. While Stefanie appeared poised and dapper in a petal-lapeled orange dress, Chris did his part to physicalize the recklessness of the new work. What started with just unbuttoned shirt sleeves billowing around his wrists and disheveled clumps of hair mashed over his eyes ended with a Chris Farley-esque flourish, athletically stumbling into a guitar-slinging pratfall as the set ended.

After satisfying the crowd with smattering of old songs like “Needy” from Album of the Year and “Some Tragedy” and “Keely Aimee” from Help Wanted Nights, The Good Life tried out some new material. And while we might think of Kasher’s myriad projects as helpful outlets for his songwriting, it’s inappropriate to simply imagine ideas popping through some kind of mechanical sorter. Cursive in one pile. Solo work in another. The Good Life in another.

He clearly has an idea of what The Good Life sounds like. For good reason. Drootin-Senseney, Lewis and Fox together relish in a kind of off-center fun. And the new songs come off like they’re leaning into the pop-rock sensibility and the overt emotionalism of their predecessors. For example, there were two new songs where Kasher plays weepy dual guitars with Fox and another pop punk sprinter, the bath of cold water with which The Good Life seems so fond of punctuating album soft spots.

The only rust to be seen you wouldn’t actually call rust. Since Lewis and Drootin-Senseney had played earlier that night with more recently active bands, we’d already seen them heads-back, big smiles and uninhibited. There was a lot more tangible concentration in play with The Good Life, eyes ahead and thinking back on old songs, that are admittedly (even on the record) stylistically uneven. Drum fills and chords don’t hit clean or right where you’d think they’d hit. They’re as playfully crooked as Kasher’s overtly fallible — or even unreliable, if you like — stories about relationships. Ultimately, everyone hit their marks with little more than a furrowed brow.

The songwriter and singer, though, was in very relaxed musical form, perhaps most notably on “O’Rourkes 1:20 a.m.” where he expertly navigated the space between naked murmur and chin-up howl. He sent the cacophonous end of “Album of the Year” tumbling with deservedly wretched gusto and looked on with a grin when Drootin-Senseney took her brilliantly sardonic and vulnerable lead on the perspective-shifting “Inmates.”

“We’re the ones who are psyched,” Kasher repeatedly insisted when the crowd whooped for both new and old songs. Pretty encouraging argument for a rekindled band to have with its fans.

* * *