It’s not a secret. If you’re holding the mic and penning the words in the music industry, you’re more likely to get the attention. To be perfectly honest, when it comes time to request interviews from publicists, writers will ask to talk to the songwriters. It seems closer to the action that way: a more central take.

With this feature, we’re looking to highlight the band members, happy to eschew the spotlight, and the consummate players. We’re talking about the person who can play eight instruments without blinking or the drummer who’s defined every band he’s been in with an uncommon style of playing. They don’t receive enough acclaim, so in the below interviews, we’ve asked six perennial Nebraska musicians about their many acts, roles and talents.

Of course, we imagine you’ll be able to think of a slew of other players and instrumentalists who deserve inclusion here. We can, too. Leave your suggestions in the comments or email them to editorial@hearnebraska.org. We’re planning on a second installment of this idea in the very near future.

* * *

Megan Siebe

Currently: Simon Joyner and the Ghosts (viola, keys, vocals, “anything else Simon needs”), Skeleton Man (keys and synth), Solo Project (guitar, vocals, strings), Anniversaire

Formerly: Cursive (Waiting Room Residency, Ugly Organ Live Recordings), The Subtropics, Noah Sterba and the Cocktails

photo by Bridget McQuillan | questions by Andrew Stellmon

Hear Nebraska: What are the challenges (other than scheduling) that come with playing such a wide variety of music? What do you enjoy about it?

Megan Siebe: There aren’t too many challenges if I’m on top of my game. Sometimes, when I play multiple instruments in one group, it’s difficult to keep track of what I play for each song and how I’ll make that switch during the show/practice. With Simon, what I play depends on who’s playing that show with us. I usually bounce between viola and keys/organ, but if we’re in need of a bass player, I’ll do that too. That’s why I carry around a notebook that has what I do for each song and anything else I’ll need to remember (chords, settings, etc.).

I love being able to play with so many great musicians and see their song writing process, the way they rehearse, and to be a part of so many various styles of music. I don’t get tired of one genre and I get to develop my skills on various instruments.

HN: How do you compartmentalize playing for each band? Do you find it difficult to wear that many different hats?

MS: I mentioned that notebook … without that lifesaver, I get a bit forgetful of what we rehearsed and what I changed. I try to write down any new ideas I have, new chords, and settings I use for each song/group. Usually, the songs become more engrained as we practice and I don’t really refer to it that often during an actual set (except for the settings), but I’d consider it my security blanket.

Although it may sound crazy to play with a lot of groups, I don’t feel that it’s difficult to wear all those hats. A long as I’m somewhat organized and we communicate well, I don’t run into too many scheduling conflicts.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Epm-WM6morI

HN: How long have you played with Simon? It sounds like he tries to squeeze every last drop out of you. What is he like to work with?

MS: It’s funny you asked how long I’ve played with Simon, because we both can’t really remember when I started playing with him. I believe it was back in late 2008 or early 2009 when he first asked me to play cello with him. Then, when he mentioned needing someone to play violin, I told him I was learning, so I started playing both instruments. For our first tour, I added autoharp to my collection and we hit the road. That was a bit stressful to play three instruments on tour, but as long as I knew the set list and could plan when I played each instrument, I grew more comfortable.

After that tour, I decided to quit lugging around the cello and violin and started playing just viola, which was a fantastic switch. On our most recent house show tour, our drummer, Kevin Donahue, and I were the only musicians Simon brought, so we multitasked and played several instruments, sometimes at the same time: Kevin would play drums and bass simultaneously and I’d play keys and drone on viola or sing. When we recorded Ghosts and the most recent album, I wrote and played all the string arrangements, sang, and played any other instruments if needed (percussion stuff, autoharp).

Some might think that sounds like he’s tried to squeeze every drop out of me, but I don’t see it that way. Simon’s very laid back to work with and loves to have each musician play in their style to his music. He’s great at telling us what he wants from a song but also listens to our thoughts and ideas. I feel grateful to be able to play with him.

HN: You played for Cursive during their Waiting Room residency. Is there any added pressure to playing a show when you know parts of it are being recorded for a specific purpose?

MS: I was a little nervous about being recorded, but overall, it didn’t throw me off too much.

What made me more nervous was playing a specific part that has already been written and recorded. When they asked me to play those shows, I sat with the Ugly Organ recordings and listened to the recorded cello parts, learning them by ear. Then I’d write little notes to myself so I wouldn’t forget how they went. I wanted to do justice to the cello parts, and with that added pressure of it being recorded, I wanted to play each line as close to the recordings as I could. Hopefully, they turned out!

* * *

Jon Augustine

Currently: Kill County, Bus Gas (bass)

Formerly: Masses (bass)

photo by Andrew Dickinson | questions by Jacob Zlomke

Hear Nebraska: All three bands (I’m including Masses [RIP] here) are pretty vastly different in style. When you’re playing the same instrument in each band, how important is that? That you’re able to vary what you’re doing within the parameters set by the bass, I mean.

Jon Augustine: Medium important, I’d say. If I only knew how to make cheesy eggs, I wouldn’t be very good at making lunch, but if I knew how to make cheesy eggs and a nice ham-and-cheese sandwich then I could make breakfast and lunch. If, then, I learn the art of a perfect cheeseburger, I could satisfy your specific breeds of hunger for an entire day.

What I’m saying is that every meal I make has cheese, but how the cheese is used and what the cheese is getting all over can really influence the entire meal’s identity. Different meals call for different cheese techniques. Does that make sense? But of course, there are those of us who are less persnickety and we might have a cheeseburger for breakfast and cheesy eggs for supper, and that is why during, say, a Kill County song, you might hear me play something that sounds like it’d work nicely in a Bus Gas song. Some might suggest that this willingness to let a lunch item into the breakfast menu give me a leg up in the creative process. I’d be curious about what an actual real life kitchen chef would think.

While I’m metaphoring and sounding a bit prideful, I’ll also toss this out there — Masses (now long lost to the compost pile) was one of the greatest grilled ham-and-cheese sandwiches that was ever prepared in the state of Nebraska and, in my opinion, not enough people had the horse sense to give it a taste while it was steaming on a plate in front of them. Too bad!

HN: I know you can play guitar. Have you ever wanted to play something other than bass in a band? Why bass?

JA: I play bass mostly because my paws are too big to play guitar the way I really want to play guitar. In elementary school I dreamt of being a drummer, but Mom talked me into learning clarinet because we had one laying around the house that was just gathering dust. So, I shelved the drum dream about 20 years ago and it’s been up on that shelf ever since.

Learning a woodwind instrument was good though, and I credit much of my kissing repertoire to the mechanics I developed on that clarinet.

HN: How does your songwriting involvement vary from band to band? Do you have a preference?

JA: They’re all wildly different experiences, and I have no preference. I’m unfamiliar with the quirks of parenthood, but I imagine that being in multiple bands is like having multiple children in that I love them all equally. I will say that I like to have Mike Vandenberg and Eric Nyffeler write my bass parts, but unfortunately that only happened a handful of times in Masses. I really enjoy playing in Bus Gas because I can play the same note for however long it takes me to figure out the next note I should play — usually plus or minus 3 minutes.

* * *

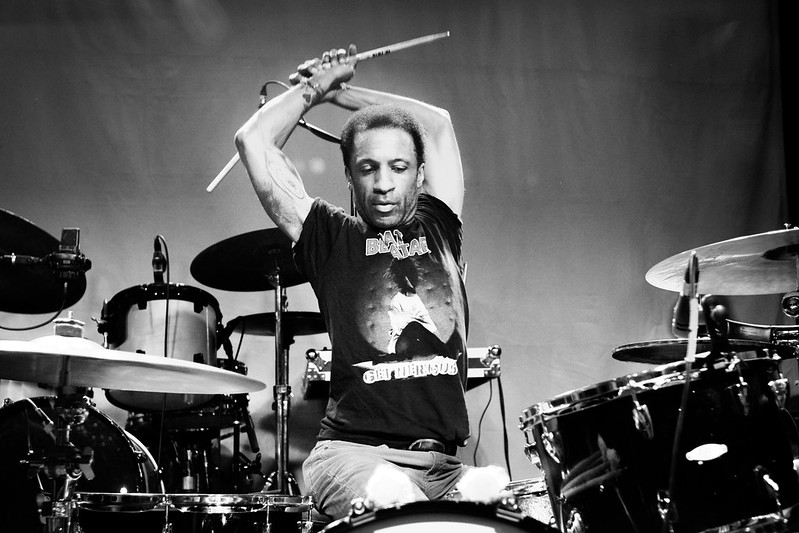

Roger Lewis

Currently: The Good Life, Oquoa (drums)

Formerly: Conduits, Neva Dinova, Grander, Daily Press, Glance To The Sequel (Blue), Bright Eyes tour (drums)

photo by JP Davis | questions by Chance Solem-Pfeifer

HN: Both Oquoa and Conduits are bands (that for me, anyway) are long on ambiance and wide/broad sounds. It always strikes me, then, that your drumming gets to have a puncturing effect at some of the more exciting moments. (“Top of the Hill” is maybe my favorite example.) What’s it like on your end to drum in a bands that you know are going to spread way out across a soundstage?

Roger Lewis: That’s true! I have always liked that about those bands in particular! I have always felt that a perfectly placed crash can punctuate some of the more exciting moments and can give the song this emotion. I love setting into an awesome groove and then building up to this climax with bombastic, majestic playing.

HN: The Oquoa album is one we’re always trying to get more ears on because of how little fanfare it was released with. Personally, what’s your favorite track on the record and why?

RL: I really like “Yellow Flags.” That song really gets the essence of my playing. I like the simplicity of it. I like the rock aspects. I like the groove. It’s a long one, and it can be hypnotic at times. It’s the kind of song, to me that when listening to it, it feels like you are on this magical drugged journey without the drugs!

HN: What part of The Good Life touring and recording this winter has you most excited?

RL: What can i say about that band? Some of my best friends are in that band. Timmy, Stephanie and Fox are the best people to be around and make with music with … Anyhow, we are making a new record this winter. We actually start recording on Jan. 7. We just finished writing for it, which has been a lot of work and fun, but, holy shit, I love what we coming up with. I truly believe that this record has a bit of everybody’s personalities. It’s been a minute since we last put out a record, and we have all done a lot of growing, and getting better, and you can hear and see it with this new batch of songs.

HN: Went back to the Top 12 albums list you put together for HN a few years back and saw Tusk, one of my favorite all-time records just to talk about, for how weird and wonderful it is. Especially in the percussion section. You have a favorite moment of drumming on that album (or maybe how the drumming sounds recorded?)

RL: Fleetwood Mac! Tusk is such an incredible record! It has so many things going on that make a great record. The tones that they created. The way they use space. The simplicity of it. The songs themselves. Mick Fleetwood is such a special player to me. Anyone that knows me well has had to listen to my spiel about how awesome he is. His crash hits are always tasteful. He places his fills in all the right places … I try to emulate Mick Fleetwood to a point, but after so many years and loving so many bands and listening to so many players, I still find myself blown away by what he does.

* * *

Jordan Elfers

Currently: Powers, Thirst Things First, Universe Contest (drums)

photo by Andrew Dickinson | questions by Jacob Zlomke

Hear Nebraska: Why do you play drums over anything else?

Jordan Elfers: I’ve always been a tapper. They wouldn’t let me play drums in grade school because I didn’t know piano. I picked them up a few years back, and now I’m just in love with drums.

HN: Each band you’re in is, for lack of a better term, a high-energy rock band. Are there differences in playing with each? Like what?

JE: There are definitely differences between the bands. TTF is very straightforward, the way those songs are written make it very difficult to add anything crazy. It keeps me in the pocket a lot more than the other bands. Joining UC is teaching me better use of dynamics and simplification. Powers is my workout these days, but four practices a week between three bands is definitely helping me condition and grow chops … and spend less money at the bars.

HN: How does your role in each band, other than “drummer,” vary?

JE: In TTF, I play what I’m told and act as a robot. I haven’t experienced much writing in Universe Contest yet, so I’m not sure what to expect. We all write together in Powers. I get to try new things, and if they’re terrible, someone will let me know. It’s interesting that each role and each band is so different to me, but at the end of the day, I’m just the dude hiding in the back hitting things. I’m very comfortable with that.

* * *

Vern Fergesen

Currently: Travelling Mercies, John Klemmensen and the Party, Matt Cox band, The Willards, Brad Hoshaw and the Seven Deadlies, The Fergesens, Heather Berney, and Reggie Shaw and the Whiskey Rebels.

Formerly: Underwater Dream Machine/Bret Vovk, Nick Carl and the meadowlarks, Cass (Brostad) Fifty and the family gram, the Prairie Gators, Steve Byam, Beef of the Sea, Capgun Coup, Yo Dirty Mama’s Basement Boogie Band, and others.

photo by JP Davis | questions by Chance Solem-Pfeifer

Hear Nebraska: On John Klemmensen’s recommendation from the studio the other day, I’ve been listening to “Elkhorn.” Really nice song, and seems to run the gamut of love, relaxation, crisis and death in a 2:40-second song with no chorus. Strikes me as the sort of song that sounds like it was a release to write. What was its genesis?

Vern Fergesen: It was definitely a release for me, especially as I had not written a song for nearly two years before that one. I think that writing songs became much more difficult for me after working so closely with the great Jeremy Holan. We worked together intensively for many months putting together the Motel album. His lyrics were of such quality that suddenly everything I had written up to that point seemed stupid. I now had to contend with a much higher standard for myself, and my output as a writer nearly ground to a halt.

However simple and meager it may be, I consider “Elkhorn” to be my first truly mature work; written honestly in my own voice and not in youthful imitation. Its genesis consisted of 3 or 4 months of trying desperately to force a song out of myself. I had written plenty of songs before, but suddenly I just couldn’t do it anymore. It terrified me to the core. I tried to write something every day. I kept a dream journal. Sometimes I would have an idea, get excited, then wake up the next day and realize it was garbage. It was creative constipation, i needed release big time.

As the weather started getting nicer, I began to drive out by my parent’s house on the Elkhorn river very late at night. There was a secluded spot right on the water, just about the size of my kitchen. I would bring my guitar and build a fire, smoke some weed and eat cashews and just listen to the river and the birds. All of the noise in my mind began to dissipate, and I felt content to just sit there, to simply exist. After a few weeks, this song started to appear. After I had finished it, it felt like I had said everything about myself without really saying anything at all. I’m always a bit surprised when someone says they like that song, because it feels more like I wrote it for myself.

HN: I know you primarily for your bass work, but you played that Korg mini-synth really well on the radio last month. Can we have a full list of what you can play? What was your first and your latest instrument?

VF: I like to think that a musician can make music with any object, as long as they have something to say. Music is a means of expression and enlightenment; once you learn to express yourself in one language, each subsequent one becomes easier. Each instrument has a specific purpose and gives the player a unique perspective on creating music.

In bands, I’ve recently found myself drawn to the role of bass player for some reason. Maybe it’s the distance from the spotlight, maybe it’s the subtleties of rhythm and touch that can add so much more to the impact of a song than most people would realize, or maybe it’s just so easy any idiot could do it. Who knows? For whatever reason, I am becoming a bass player, and I’m OK with that.

I just bought that microkorg a month or two ago, and it’s really opened a door to a new world of sound for me. I’ve been playing piano for years, but I’ve never been able to play lines as articulately or create as broad of textures as I can with the synthesizer. I love crafting patches. Understanding the frequency and harmonic spectrums. Learning about oscillation, sequencing, phasing and filtering; it’s all about waves. Waves upon waves within waves. I find it fascinating and inspiring, it’s kept me very busy lately, and I hope that I can put it to good use in the future. John Klemmensen has been very gracious in allowing me to explore these ideas over his songs.

HN: I don’t want to start competitions, but as a member of so many Omaha rhythm sections, what drummer in all the bands you’ve played in do you connect with on the most instinctual level?

VF: Short answer, Walker Gerard (Matt Cox Band). He has been a part of my family ever since he was my older brother’s best friend in high school.

My first band, Stone Gruv, was Walker and I jamming in his mom’s basement. We mostly wrote crappy songs and covered a lot of Black Crowes, we might have played one public show. We evolved slowly together, through shifting players and shifting styles (including the legendary death metal band, “ALLOY”). Eventually, we formed The Fergesens together with Andrew Stickman and Wil Goldfein. The Fergesens don’t play much anymore, but I like to think I can still call them up at any time and they would be down to jam. After 15 years, it sometimes feels like Walker and I think with the same mind when we play.

Also: Scott Gaeta, Nick Sortino, Ryan Haas, Jerron Storm, Wayne Brekke, Daniel Leonard, Henry Phelps, Steve Monson, Paul Valdivez, Doug Montera. Each one of them is a stone cold killer. I love drums and drummers, which probably has a lot to do with my transition to bass. Percussion has the longest tradition in music, which I believe gives drummers a certain ancient primal wisdom.

HN: I imagine you have to be a bit of a human jukebox to remember your own songs and all those bands. Is your recall of songs a really intuitive thing, as in “what’s the key, and let’s do it!” Or are you more structurally-minded when it comes to memorizing songs?

VF: Good question, I’d say it’s a bit of both.

On the intuitive side, there’s sort of a trade secret; ear training. With plenty of discipline and repetition, it’s not hard to recognize intervals, patterns, harmonies, and progressions by ear automatically. If you mix that with an understanding of the common tendencies of whichever idiom you are trying to be fluent in, you can develop the seemingly magical ability to guess what someone will do next when playing a song you’ve never heard before.

Structurally, most of these songs are not very complicated. To put things in perspective, I once memorized a single movement of an Edvard Grieg piano concerto-about 15 minutes worth of music. It took me 3 months of focused practice for hours everyday. Recently, I memorized 50 country covers (about a quarter of which I had heard before). It took me four days. Of all the songs that I perform regularly with my bands, I’d imagine it’s no more memorization than an actor would undergo for a large role.

Most importantly, what really helps the memorization process is the quality of the songs. If it’s a song you love and relate to, you internalize it and it becomes a part of you. At that point, you aren’t thinking in terms of notes anymore, you are performing an act of devotion. I’m sure that even most people who consider themselves “non musical” can remember every word and note to a song that they once loved but have not heard in years.

* * *

Benji Kushner

Currently: Josh Hoyer and the Shadowboxers, Mezcal Brothers, The Wondermonds (guitar)

photo by Cameron Bruegger | questions by Andrew Stellmon

Hear Nebraska: For those three bands, which are fairly different, what do each of them demand of you on guitar?

Benji Kushner: Let me give you a little bit of context. A lot of people tease,“You’re in all these bands. You’re in every band!” Some friends did a meme about how I was in every band ever. And they placed me in all these great rock n roll bands and reggae bands, just stuck my profile picture in it.

I really didn’t set out to be in three bands or anything. In the summer of 2012 I realized I wanted to have a little easier time financially, you know? I was doing alright but things were tight. I moved in to a house that was nicer for me and my daughters, compared to a one room apartment that I converted into a two bedroom, and I just wanted to have a little more money to make things better. I decided in my head that I was gonna play more music, that I didn’t wanna take another job. Friends had been kind enough to invite me up onstage in their bands. The Bottletops, Kris Lager, Tijuana Gigolos. I’ve been playing with the Mezcal Brothers for almost nine years.

Josh Hoyer approached me and said “I’m getting this thing together.” We didn’t even know it was going to blossom the way it has. We thought it would be cool, we thought people would enjoy partying and dancing, and there wasn’t a lot of funky soul like that. I liked the way he wrote and I knew the other players were very good, so I said yes. Literally, I think within probably 2 weeks’ time of thinking this in my head and not really worrying about how it was gonna happen.

And I’m not kidding, within the week, these buddies of mine from way back … we said someday when there’s time we should just form a band that plays [late ‘60s funk] exclusively. We made that pact a long time ago because we had so much fun playing it. So here it was like literally a couple of weeks … these two groups of guys invite me to do really cool things. It’s literally what happened. It became a really intense period of music for me.

As far as what’s different, or how I approach the groups differently, well of course you’ve got Rockabilly [with Mezcal Brothers], which is just incredible music. Gerardo and Charlie Johnson taught me so much about playing rockabilly. I hadn’t played except for a very brief time. I grew up listening to some of it for sure. I was really intrigued with Jerry Lee Lewis since I was a tiny kid.

The thing about rockabilly is that it’s really quite complicated. You can have a song that’s more swing. It’s more of like a jump tune that leans more into the jazz harmonies. Or you can have a song that’s really straightforward, gut-busting, and one chord and … here’s this electric guitar and I’m just gonna wail on it. Just weird hammer ons and bends. Not a jazz tradition, but as delta is to other types of blues. Some of that hillbilly swinging rockabilly is really primitive and just like one-chord stuff.

I like being able to bounce around between more primitive style of playing where I’d just wail on the guitar and not even know what’s gonna come out, because they were just figuring out how to use electric at that time, some of these guys. And then bouncing over into a jazz solo, based on what a horn might do. That freedom within rockabilly is frickin’ cool. The music goes all over the place. I love that. We’re a four piece. Gerardo is playing acoustic guitar and singing. Charlie takes a few solos here and there. Primarily, if there’s a spot where somebody stretches out, its gonna be a guitar. Its gonna be me. Its a very intense experience to have songs that consistently have electric guitar breaks, and that’s a little different than Josh Hoyer and the Shadowboxers.

What a wonderful set of challenges in the Josh Hoyer and Shadowboxers situation because here, now you’ve got multiple soloists. You got a big band. Nine piece, or when we’re playing a little stripped down without some of the singers it’s a six piece. But still you’ve got a trombone, you’ve got a saxophone, obviously Josh on piano or organ, Justin Jones on the drums. He has features on the drums. The challenge and the excitement there is to make a group sound where everyone contributes. Its a balance that occurs between a lot of good players and so arrangements really come in to play. It’s not just playing the head of a tune and then there’s a guitar solo. I might not even play for 16 measures. Some people might say, “It’s not as much work.” No, it’s just a different kind of work. It’s like learning to play less and really listen to the other players. It’s a really cool challenge to find just that right riff or chord progression that just seems right in there with everyone else.

One of the challenges was [that] I never really used a wah-wah pedal in my life … until oddly both the Wondermonds music and then Josh’s cover songs and originals. You’ve got the really cool wah effect going and that was like “wow, I’m gonna set my foot up on this thing.” I mean, don’t get me wrong, it’s not like I’d never played around with one, but I never played one with a band. I’d never soloed with one.

With the Wondermonds, it’s a totally new experience. Trying to play these Meters tunes that are so idiosyncratic, so New Orleans funk, late 60s, no vocals. And of course the other guys were coming to terms with playing a new style too but we loved it. That was really challenging. All of us are in multiple bands, so we have a hard time getting together regularly enough, but I think given the rehearsal starved nature of the band, we’ve come along real quick. Those songs are hard. First we just started to get where we could just play the songs and sound pretty good doing them exactly like those bands. Then … we started to loosen up and put our own signature on tunes. We started to manipulate some of the riffs and stuff. I didn’t just completely copy [Steve] Cropper [of Booker T and the MGs]. It sounds simple, but if you actually want to play it where it sounds right, it actually takes some real dedication. To learn it was really exciting. And it made you realize how great those guys were.

I guess it’s just whatever format you’re in, you’re just listening to the other players and just making sure that everyone takes a role that is needed but not stepping all over other people. That’s universal. I don’t care if it’s a two-piece, I don’t care if it’s just me and my guitar, I don’t want the guitar to step on the vocals. I want them to complement each other. But certainly in a four piece versus a nine piece band, these things change a lot. It’s a total commitment to the song. That’s what all players have in common.

HN: You always look so damn happy when you’re playing. And I can tell why: You just got excited [and talked] for 20 minutes. What’s with that?

BK: Yeah, I’ll tell you exactly what’s with that. It’s a culmination of a few things. I was raised by my really wonderful parents and had really wonderful siblings and extended family with an appreciation for making song, making music. Folk songs. Pop songs. We just enjoyed that kind of thing together, and sang together. Once I started playing an accompanying instrument like the guitar, the whole family was totally excited about it. They were filled with joy and I was as well. The way I’ve grown up has certainly anchors that feeling. I was just actually born with this driving passion and this love of music.

My best friend moved away when I was a kid, we did everything together and I was really bummed. And then a short time later, maybe within a year … the guitar became my best friend. I really enjoyed figuring out how to play it. I wrote a lot of songs in my teens just sitting there in my room. Four walls, by myself. I learned a lot of songs the same way. In high school, we played Black Magic Woman when I was 15 for the high school, for talent night at [Lincoln] Southeast [High School]. I was kind of nervous, you know? I was nervous for a long time playing. I still get a little nervous but I’ve learned that that’s a good thing. To look out when you first start playing, you don’t know what people are gonna do. I’m used to four walls! And they’re just groovin. That was a really exciting thing. To play something and to have people join in and feel with you … to share it like that and have people dance and groove and forget about whatever happened during that day or week that was bummin’ them out, it’s a huge blessing and a gift and it fills me with joy. I think I just shoot for that.

HN: If Josh and Gerardo had a battle of stage presence, who would win?

BK: [Laughs.] Wait a second … If they had a battle of stage presence? Is that what you said?

HN: Yes. I’d like to think that we’d all win.

BK: Yes. I think the world would win. I think Gerardo would strike a stance, you know? Start getting the groove down on the acoustic guitar. And he would strike a classic Gerardo pose. Josh, at the same time, would be right there at the piano at the other end of the stage and lock into his groove. But I tell you, when the sparks would really fly is when Gerardo starts to either get up to the edge of the stage and lean out at people and starting moving his feet around and legs around, waving the guitar up in the air, catching people’s eye, and of course at that point … Josh would, of course, get up out of his position at the organ and just grab the mic — this is assuming they had a band that would help them battle — and he’d get up off his stool and come to the front stage and really start rapping and getting right in people’s faces.

The roof would be blown off the Zoo if they were truly doing battle in such a way. But I think the surprise element would be that all of a sudden Charlie Johnson, who’s been backing Gerardo, climbs on top of his fricken bass with his ankle hanging over the headstock and steals the show. And then of course … I think Tommy would probably raises his bell super high and come up with the most powerful trombone riff. I think there are players that back these guys that help motivate them to be the great front man that they are, and if some imaginary battle on Olympus occurred, God, the whole club would win.