[Editor’s note: Liner Notes chronicles how Chelsea Schlievert Yates discovered music through the ’80s and ’90s while growing up in Norfolk, Neb. We hope to post a new installment every other week. Read more here.]

by Chelsea Schlievert Yates

I hated three things in school: tornado drills, school lunch and most of all, PE class. At my grade school in Norfolk, most kids considered it a second recess, but to me it was 50 minutes of hell I was forced to endure between reading and math.

I wasn’t coordinated, and I wasn’t fast. I couldn’t kick, catch, hit or throw. I hated Red Rover and the way it made kids slam their bodies through the opposing team’s chain of human fists. I hated square dancing (part of Norfolk grade school physical education curriculum) because it required girls and boys to link arms and hold hands. And I really hated running The Mile. One or two PE classes each year would be dedicated to it, and on these days I would beg my parents to let me stay home. They never did, and so I was forced to participate. I tired easily, usually walked most of it by myself, and was always one of the last kids to cross the finish line.

Like grade school, junior high gym class was co-ed, and this did nothing for my self-esteem. It was bad enough that my athletic abilities were non-existent, having to be confronted with this fact daily in front of members of the opposite sex — something that was really starting to matter — only embarrassed me more. I hated anything in which I had to be a goalie. Survival instincts would kick in and I’d usually move out of the way of the ball or puck, more concerned about protecting my face than the goal.

And I dreaded days when the weather was nice. They often meant that class would take place outside with a game of softball. I was always one of the last kids picked for teams and was known as the “easy out”: the kid whose hesitant step up to the plate motivated the entire outfield to move in at least fifteen feet. I made it a personal goal to be on whatever team was at bat and would loiter at the back of the line to avoid being called to bat, praying that the gym teacher didn’t notice.

Needless to say, when I learned that only one year of PE was required in high school, I was relieved. I decided to take it my sophomore year to get it out of the way. Enrolling in that class turned out to be one of the best decisions I made: 10th grade gym class was where I met my good friend Sara. She dyed her hair red with berry-flavored Kool-Aid, something my parents wouldn’t let me try. For PE clothes, she wore band T-shirts that she inherited from her older siblings, and during gym class, she introduced me to guys like Ian MacKaye, Perry Farrell and Layne Staley.

When it came to physical education, Ian, Perry, Layne, Sara and I were an unlikely bunch. We found ourselves in an even unlikelier gym class. It turned out to be an all-girl class that included of a handful of the best girl athletes in the 10th grade. And then there were the rest of us — the majority — who, for the most part, weren’t athletic. But the instructor decided to do something that caught everyone in the class off-guard: she tailored the class to us — the uncoordinated, the couldn’t-care-less, the out-of-shape, the last picked for teams. She wanted to instill in us all that we didn’t have to be varsity athletes, starters or cheerleaders to find meaning or enjoyment in exercise. We could do it; we just had to try.

So instead of practicing lay-ups, we did aerobic videos. Handball, that evil game which had left me with a nasty bloody nose the year before, was replaced with tennis. We covered a unit on bowling, which meant we got to leave school grounds for Norfolk’s bowling alley conveniently located across the street. When the weather was nice, we went on walks. Sara and I would talk the whole way about our favorite grunge and alternative bands: Alice in Chains, the Screaming Trees, Jane’s Addiction, Fugazi, Nirvana, Pearl Jam. Somehow the Counting Crows found their way into this mix.

Except Sara, a lot my friends couldn’t stand most of August and Everything After, the Counting Crows’ 1993 debut album that had come out our sophomore year. Its heartfelt ballads were too depressing for Friday night get-togethers and cruising Norfolk Avenue. But that’s why I liked them. Adam Duritz, the band’s lead singer and primary lyricist, wasn’t afraid to share his demons of sadness and depression. Fifteen-year-old me found his words melancholic, pure, plaintive and honest.

I adored my grunge rockers, but there was something refreshing about the Counting Crows: They were softer and funkier than grunge, and with their rock sensibility and moody, introspective lyrics, they spoke to my teenage confusion in a way different from Nirvana and the others. In my bedroom, I could close the door and scream along with Kurt Cobain, but I could lie in bed and journal with Adam Duritz.

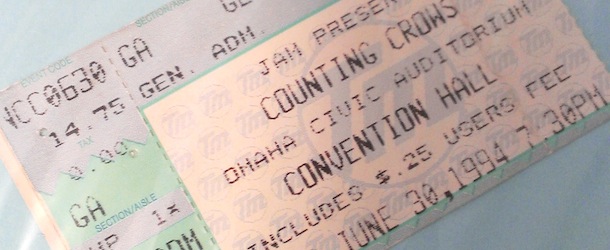

One day near the end of the school year, Sara mentioned that the Counting Crows would be playing a concert in Omaha. Would I like to go? She and her sister were heading to Omaha that weekend — if so, she’d pick me up a ticket from the Ticketmaster counter inside Homer’s Music. I said yes. It would be my first concert officially without parents, and I couldn’t wait. I’d figure out how to get permission later.

I had lost such battles before. For Norfolk-area kids, seeing live music could be difficult. My hometown was about two hours north of Omaha and Lincoln, cities where bands — if they even came to Nebraska — would play. For me, going to a show meant convincing my parents to let me drive two hours with friends on the highway each way. It also meant we’d be navigating streets like Dodge in Omaha and O Street in Lincoln, which were much busier than any street in Norfolk. And, of course, there would be the concert itself.

All of these factors put my mom on edge. She had denied my request to see Alice in Chains earlier that year because a) it was in Omaha, b) on a school night, and c) she didn’t like their name. She said it sounded too much like that “Guns in Roses band” whose show at the Omaha Civic Auditorium a few months prior had nearly resulted in a riot, according to the news stations.

I spent days arguing my case. I explained to her that Adam Duritz was a far different kind of musician than Axl Rose, and that I was sure Counting Crows fans had little in common with Guns N’ Roses fans. I pointed out the facts — that the concert was taking place on a Thursday evening in June, so it wouldn’t interfere with school, and that Sara’s older sister was going and would be doing the driving. I also called witnesses: I asked my friend Bryan, who worked for my parents, if he could mention to my mom that he was going to the show, which he was. My mom liked him, and shortly after their conversation, the verdict was handed down. Permission granted.

***

I have to admit, I don’t remember much about the concert itself. I know that it took place in the Omaha Civic Auditorium’s Convention Hall and that it was opened by Sam Phillips (the singer-songwriter, not the Sun Records founder) and the Australian band Frente. I saw someone crowd-surf for the first time, and I bought a concert T-shirt from the merch booth. I remember the feeling of the hall erupting when Charlie Gillingham strapped on his accordion and played the first few notes of the song “Omaha.” I was very confused by this. To me, the song was bleak: a comment on the futility of life, a cycle always moving, pushing down who or whatever stood in its way. Yet, we Nebraska kids cheered it on. Why?

What I remember most actually happened that afternoon before the concert had even started. We arrived in Omaha, parked the car in the Old Market, and Sara’s sister said we could go explore on our own provided we met back at the car before the show. We had an awesome day, which included lunch at Zio’s Pizza, CD-shopping at Drastic Plastic, and a spin through The Retro. We were free of parents and older siblings. We were on our own in a city bigger than Norfolk, and we were going to a rock show. By teenage standards, we were cool.

As we walked back toward the car, we encountered a guy coming toward us. Aside from his dreadlocks, he looked like someone I knew. He wore shorts, a T-shirt, and had Dr. Martens boots laced up his pale legs.

Sara immediately recognized him as Adam Duritz. Once she did, I panicked. What would we do? We couldn’t dare talk to him, could we? After all, he was a rock star! Was it cool to say something, to ask for an autograph? Would we seem totally lame? I was sure that my friend, who had been to more concerts than me, knew the protocol. “What do we do?” I whispered.

I was surprised to find her just as awestruck as I was. “I don’t know — you say something.” “No, you!” “No, you!” “You say something!” “Eek! Like what?” “I don’t know!”

As we freaked out on the sidewalk, Adam Duritz passed us. “Hey,” he said nonchalantly, “How’s it going?”

He had spoken to us. And we were paralyzed. After blankly staring at him for a few seconds, we managed to squeak a “Hi” and “Fine” in return. He nodded in return and walked on.

Once he was well out of hearing distance, we flipped out. “Oh my God, we are the lamest.” “All I said was ‘hi’? What’s wrong with me?” “So stupid!”

In all truth, it was probably how a lot of teenagers would have reacted. For me, it had been the closest brush with a celebrity that I had ever encountered. Way more impressive than the time I got to shake hands with Donny Most, Ralph Malph from TV’s Happy Days (something my dad was really excited about, though the experience was lost on me as I knew little about the show beyond The Fonz) or the time that my sister and I received autographed headshots of Christina Applegate and David Faustino upon joining the Married…With Children fan club. But as embarrassed as I was with my awkwardness, inside I was beaming: Not only could I tell people that Adam Duritz totally came up and talked to me on the street in Omaha, but I had discovered that my friend — one of the coolest alternative girls in the 10th grade — was an excitable kid, just like me.

***

A few years later, during a pretty intense bout of depression while I was in college, I made myself get rid of all my “sad” cds. I thought that doing so would help alleviate the feelings of darkness that were growing inside me. August and Everything After was one that had to go. With a permanent marker, I blacked out “Chelsea” as I had written it on the disc (in those days I wrote my name on all my cds, just in case they were mixed up with those of my dorm mates). The moodiness in which I had found solace as a teenager had begun to give me anxiety in college, not unlike that which I experienced in my early PE classes. I felt as uncoordinated in life as I had in the gymnasium. It was like I was back on the ball field, the “easy out,” the last picked. Good days I’d get up and go to class; bad days were spent alone in my room.

I sought refuge that summer with Sara, though I don’t know if she knew that’s what I was doing. She had moved with her boyfriend to southern California, just outside of Ventura. We were about five years and 1,700 miles from Norfolk High School, and, as friends tend to do, we reflected on our time there. Sara remembered the day in PE that I won the class free throw competition. Somehow I had found the “sweet spot” on the gymnasium floor and from it landed 23 of 25 free throws in a row. We laughed, recalling one of our classmates — a varsity basketball player — glaring as my perfectly arched shots whizzed by, breaking her record with each swish through the net.

We revisited the Counting Crows concert we’d attended together, laughing at how silly we’d been when Adam Duritz said hello to us, and remembering how intense it was witnessing the concert hall explode with “Omaha.”

Had we Nebraska kids been so starved for recognition on the national music scene in 1994 that we’d take whatever we could get? There had been Bruce Springsteen’s 1982 album Nebraska, but it wasn’t of our generation, and — having been created in Bruce’s New Jersey bedroom — it wasn’t really a product of the plains, anyway. There was Mannheim Steamroller, on a different end of the musical spectrum, and bands with potential to make it big like The Millions and Mercy Rule. Lincoln native Matthew Sweet had made some ripples by 1994, and 311 was starting to play in the deep end of the national alternative music pool — but it would still be a few years before Saddle Creek Records and bands like Cursive and Bright Eyes splashed the Omaha sound across the country.

Yet maybe there was something more. Perhaps, “somewhere in middle America,” as the lyrics go, with roots deep in Midwestern soil — ground that had been rolled, tilled, sowed, planted, pricked, pulled and eventually paved — we knew more about life than any of us led on. Maybe we couldn’t articulate it, but perhaps we knew it deep in our bones.

Life is cyclical. It turns people over as ploughs turn the earth over. Change is inevitable. We will all die one day. But until that day, we live. How we live, and how we choose to view the world around us, that’s up to us. My friendship with Sara came into being in a high school gym because of a class I thought I despised. I grew up struggling with exercise but as an adult have fallen deeply in love with yoga and the obstacles it’s allowed me to overcome. There will always be songs I cling to and then part from: beautiful and tragic, shallow and deep, ugly and loud, haunting and magical. I will meet rock stars and other celebrities, but I will find more artistry in and will come to admire more of the everyday folks I get to know. I’m still visited by my own demons of depression, but I’m fortunate to know that, like clouds, they will pass.

As Duritz tell us in the lines of “Omaha,” when we “get right to the heart of matters / it’s the heart that matters more.” Maybe not exactly in his words, but I try and remind myself of this every day.

Chelsea Schlievert Yates is a Hear Nebraska contributor. She grew up in northeast Nebraska and now lives in Seattle, Washington. Reach her at cdschlievert@gmail.com.