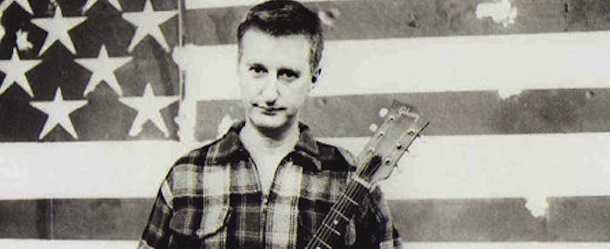

courtesy photos

[Editor’s note: Liner Notes chronicles how Chelsea Schlievert Yates discovered music through the ’80s and ’90s while growing up in Norfolk, Neb. We hope to post a new installment every other week. Read more here.]

by Chelsea Schlievert Yates

My mom and dad owned Rags to Riches, a T-shirt store at the mall in Norfolk. It was one of those shops where you could pick out a shirt and an iron-on transfer and watch as the employee pressed the transfer onto your garment using one of those big heat press machines. Once that fad started to fade, the store began to morph into a Nebraska Huskers fan shop, which is what it is today. I worked there every weekend during junior high and high school from 1992 to 1996, when it was transitioning between identities.

My dad hired Bryan, a kid from our neighborhood, to work on the weekends as well. Bryan was two years older than me. Quite frankly, I’d always found him a bit annoying when we were little. If I was playing school with his sister, he would disrupt and pester us. If I’d be outside shooting off fireworks around the Fourth of July, he’d feel a need to critique my grade school pyrotechnic abilities. And he often beat me at backyard badminton, something that particularly irked me.

But I hadn’t seen much of Bryan since he started high school, and I wondered what working with him was going to be like. Was he going to be obnoxious? A know-it-all? Was he going to try and show me up in my parents’ store by selling more Husker knick-knacks than me? Fortunately, none of that happened, and it turned out that he and I got along great.

In many ways, he became the older brother I never had. When I got ready to transition from junior high to high school, Bryan coached me on everything I’d need to know to appear like I knew what was going on: where the best lockers were located, what time to get to school in the morning (early enough to check in with friends but not so early that I’d appear too eager or nerdy), which teachers to take classes from and which to avoid. When I started going on dates, Bryan would provide his two cents on the guys (which, 99 percent of the time, went along the lines of, “You can do better, Chelsea.”) But most importantly for me at the time, after discovering that I really liked listening to U2’s album Achtung Baby, Bryan started talking to me about music.

At first, I had no idea what to make of this music. It existed somewhere beyond mainstream Top 40 radio. Some of it was twangy but in ways completely different than Garth Brooks and the other artists who filled the country station airwaves. And there were women involved in a lot of it, not just on the sidelines, but fronting the bands, playing guitars and writing songs.I could say that Bryan was a big U2 fan but that really doesn’t do him justice. He was also a big Uncle Tupelo fan. A big R.E.M. fan. A big Lemonheads fan. A big Counting Crows fan. He and his friends were all about independent music (the name “alternative” was only just getting to Norfolk around 1992), and he started to introduce me to these bands and more. Every Saturday, Bryan would bring in his book of CDs from his car and create soundtracks for our morning and early afternoon shifts together: Billy Bragg, Juliana Hatfield, the Sundays, Mazzy Star, Matthew Sweet, the Cranberries, Toad the Wet Sprocket, the Refreshments, They Might be Giants, Wilco, Son Volt, the Jayhawks and this strange new band called Radiohead.

Thanks to Bryan, I dove into alternative music, and by 1995, I thought that music couldn’t get any better. I dreamt of joining a cool band like the Breeders, Veruca Salt or Sonic Youth or embarking on a solo career like Juliana Hatfield. I memorized the lyrics to every song on the Reality Bites soundtrack, just as I had done with the Singles soundtrack a few years earlier. (I should admit that, upon moving to Houston in 2008, one of my top priorities was finding the house in which Winona Ryder’s and Janeane Garofalo’s Reality Bites characters rented an apartment. I did the same thing when I moved to Seattle in 2010, immediately locating the Coryell Court Apartments — where the Singles gang supposedly lived — and canvassing the surrounding neighborhood.)

I didn’t like everything in Bryan’s CD book, but that actually made our workdays interesting. Take, for example, Billy Bragg. Fifteen-year-old me couldn’t stand Talking to the Tax Man About Poetry, and whenever Bryan would put it on, I’d beg him to turn it off. Eventually, he would do so, but he would always ask me to explain what it was I didn’t like about the music first. This was a challenge for me — I had never had to justify my musical preferences before (up until that point, who had cared?); I either liked or didn’t like a song. That was enough.

But it was never enough for Bryan, and soon we started dissecting the music we listened to together. Was it the lyrics? The singer’s voice? The sound of the guitar? Was it too fast, too slow? Too “out there”? Too mopey? Too raw? Too simple? Too political? Was it because I didn’t think I could relate? Did the music remind me of something, and if so, what? Did that have anything to do with why I didn’t like it? What happened when I compared Talking to the Taxman About Poetry to R.E.M.’s Green or U2’s Rattle & Hum? Suddenly things became much more complicated. And exciting.

“Waiting for the Great Leap Forwards,” the last song on Billy’s 1988 album Workers Playtime (a title I always found a bit tongue-in-cheek when listening to it with Bryan at work) baffled me: How could a song be so political and serious yet so catchy and fun? Two lyrics in particular always struck me: 1) when Billy recounts being asked by a writer what’s the use of mixing pop and politics, and proceeds to, succinctly and brilliantly, collapse the distinction between the two, and 2) the line at the song’s end in which he cheekily calls on folks to “join the struggle while you may” because “the revolution is just a T-shirt away.” Listening to this final verse while being at work, surrounded by hundreds of T-shirts for sale with emblems promoting anything from Husker football and Beavis & Butthead to Harley Davidson motorcycles and “World’s Best Grandpa” completely blew my mind. Billy provided me with my first critique of capitalism, ironically, while working a part-time job in which I sold novelty T-shirts, souvenirs, imprinted sportswear and tchotchkes.

And one Saturday — once I figured out how to engage his music on my own terms — I finally started to “get” Billy Bragg. It would be awhile before I would say I liked Billy Bragg (which eventually I did), but I had figured out an in-road, and I was so proud of myself. It was as if someone had had turned the plastic wand and opened the mini-blinds, allowing new kinds of light to flood into my teenage years. I celebrated by treating myself to an Orange Julius and a box of Karmelkorn from the mall’s food court.

I’m sure that Billy wouldn’t have approved of me supporting such corporate snack food entities, but I couldn’t help indulging. I was having a difficult enough time wrapping my teenage mind around the issues associated with whether or not I would pass my driver’s test, would anyone ask me the homecoming dance and how I could convince my parents to extend my curfew; I wasn’t ready yet to start thinking seriously about the health effects of junk food consumption, or the politics of consumerism and the fast food industry’s exploitation of the public, for that matter. (Billy, if you ever read this, please know that I got there eventually.)

Of course, all of this was against the backdrop of our weekend part-time jobs at the mall. Bryan and I opened the store together on Saturdays and pretty much just played music until other employees arrived for the afternoon shift. My parents could never understand why Saturday business was so slow before 2 p.m., though I knew the reason. Perhaps I should have been more concerned with T-shirt sales on my parents’ behalf, but how could I? Somehow they didn’t seem near as important to me as the world of music that was being illuminated before my eyes.

A few years ago, I saw Billy Bragg at a free afternoon show during South by Southwest in Austin, Texas. Temporary chain-link fences had sprouted all over Austin, creating impromptu music venues out parking lots, city parks, backyards and vacant lots. Billy Bragg played at what I think was a park a few blocks off of Sixth Street. By the time we arrived, there were too many people inside the fence so we watched from the loading dock of a warehouse across the street.

As the audience sang along with the chorus of “A New England,” I thought about the Saturday mornings I’d spent with Billy and Bryan back in Norfolk. Because of them, I started listening to music differently. I began to pay attention to song lyrics — in particular, about the “why” behind them and not just the “what” that they were about. I thought about the various ways that music was made — how instruments complemented voices, and each other, how sounds were layered to create messages and moods. Because of our Saturday morning music sessions, I began to understand that music could be anything: It could be personal, emotional; it could be political, reactionary. It could be created to push boundaries of sounds and genres, to generate new ways of playing. It could be part of a larger dialogue — responding to or carrying the torch of another musician. It could be so many things beyond simply “good” or “bad.” I just had to give it a chance to see where it might lead me.

Chelsea Schlievert Yates is a Hear Nebraska contributor. She grew up in northeast Nebraska and now lives in Seattle, Washington. Reach her at cdschlievert@gmail.com.