[Editor’s note: Liner Notes chronicles how Chelsea Schlievert Yates discovered music through the ’80s and ’90s while growing up in Norfolk, Neb. We hope to post a new installment every other week. Read more here.]

by Chelsea Schlievert Yates

“God only knows what I’d be without you.”

— The Beach Boys, “God Only Knows,” Pet Sounds

Only three of the original five Beach Boys took the stage the night I saw them at the Nebraska State Fair in 1990.

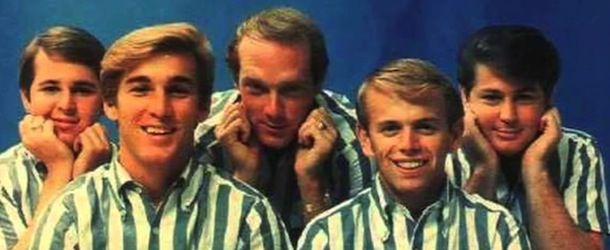

The original lineup — brothers Dennis, Brian and Carl Wilson, their cousin Mike Love, and their friend Al Jardine — never played together again after Dennis’s death in 1983. However, even since their formation as a band in 1961, their relationship — as family, as friends, as bandmates, as artistic collaborators, as business partners — had been in constant turmoil. Creative differences, drug use, legal battles, issues of mental and physical health, fights and firings had all been a part of their history, just as the songs and albums they created. And somehow through it all they were, would always be, the Beach Boys.

The Beach Boys were the first band I ever considered in terms of family. Sure, I was aware of other musical groups comprising family members: the Jacksons, the Bee Gees, the Carters, the Nevilles, the DeBarges, the Everly Brothers and the Pointer Sisters. But perhaps the reason the Beach Boys’ family dynamics made such an impact on me was because they were so much a part of my own family. No matter the conflict while growing up — who had used whose bike without permission, who had forgotten to take out the trash, who had slammed a bedroom door in protest of being grounded, who came home past curfew — the music of the Beach Boys was something on which everyone in my family could agree.

My dad had been a big Beach Boys fan and had introduced my younger sister, brother and me to their hits early in our childhood. If “I Get Around” or “Help Me, Rhonda” came on the radio while we were in the car together, he turned up the volume. Dad liked to sing along. He was particularly drawn to trying out the falsetto parts.

I remember bouncing around the playground of my elementary school with the “ba-ba-ba” of “Barbara Ann” stuck in my head and, upon seeing 1985’s film Teen Wolf, feeling so cool that I recognized “Surfin’ USA” — the song to which Michael J. Fox’s character van-surfed — as a Beach Boys song. And don’t even get me started on how much 10-year-old me loved “Kokomo.” I owned it on a cassette single, or “cassingle” as we called them. For a time, I carried it with me wherever I went, just in case there’d be an opportunity to play it. On the five-minute drive from our house to my piano teacher’s or on the highway to and from visiting my grandparents in Blair, I’d beg my dad to let me pop it in the tape deck of the family van.

Needless to say, when Dad announced at the dinner table that he’d made arrangements for us, as a family, to see the Beach Boys at the state fair, I was pretty excited. I was 12 and had decided that it was about time I started going to concerts. If that meant having to attend my first with my parents and my little sister and brother, I was prepared to do so.

A few months earlier, I’d watched a miniseries on television about the Beach Boys. Called Summer Dreams: The Story of the Beach Boys, it was a dramatization centered on the rocky relationship between the Wilson brothers and their dad, who managed the band in its early days. It shed light on the physical and emotional abuse the brothers suffered at home as well as their struggles with substances and mental illness, and, later, self-destruction. I found out that Dennis, Brian and Carl had shared a bedroom at the time they formed the Beach Boys (I had to share a room with my sister, so this was particularly notable to me) and that Brian had suffered multiple nervous breakdowns and severe anxiety from the stress of the band. I also learned that for a time in the 1970s, Dennis had been connected with Charles Manson and, impressed with his songwriting, had invited Manson to record in his brother’s home studio.

I was exhausted by the end of the biopic, as if I’d been on a roller coaster through the Beach Boys’ history that was in no way “Fun, Fun, Fun.” Overall, their story perplexed me: For all the heated arguments, walk-outs and riffs, there were as many reunifications, rehires and reunion tours. The miniseries ended sometime in the mid-1980s; yet they were still together, sometimes, still making music. Weren’t they sick of each other? Why not just throw in the towel, call it a good run, and part ways for good?

I guess because with families it’s different. It’s complicated.

***

My dad had purchased the concert tickets as part of a promotional package that one of Norfolk’s local radio stations was hosting. It included transportation to and from Lincoln via a charter bus, day passes to the state fair’s exhibits, and tickets to see the Beach Boys at the Bob Devaney Sports Center that evening.

As we waited with our fellow northeast Nebraskan concertgoers that morning for the bus to arrive, I double-checked to make sure I had packed extra AA batteries for my Walkman. I’d made a couple of tapes over the last few weeks especially for the trip. They included whatever I could record from the Rick Dees’ Weekly Top 40 radio program that broadcast in syndication via one of the local stations. Thanks to Rick, I was well-stocked with songs by Marky Mark & the Funky Bunch, Martika, Boys II Men, EMF, Jesus Jones, Color Me Badd, Tara Kemp and C+C Music Factory.

When we boarded, it occurred to me that I had never been on any bus other than a school bus before. I was struck by this one’s plushness. The seats were soft and cushiony, not springy like those found on the school bus. And they weren’t covered in vinyl, so the backs of my legs didn’t stick when I changed seating position. The aisles were wide and roomy, and conveniently enough there was even a bathroom on the bus. Was this what tour buses were like — the kind that transported rock stars to and from their gigs? I grabbed a seat by the window, put on my headphones, and let Marky Mark’s “Good Vibrations” carry me away. As they did, I wondered how the Beach Boys felt about his song having the same name as theirs.

Though I’d lived in the state all my life, this visit was my first to the Nebraska State Fair. In fact, other than the time in college when I went with a friend just to see how much fair food we could eat (one funnel cake, two cheese-on-a-sticks, and two deep-fried candy bars — terrible idea), it would be my only visit. That morning, we walked through the livestock show and ag equipment displays. I knew a few classmates involved in 4-H and FFA, but their worlds were foreign to me. I became distraught when I realized that many of the cows and pigs in the livestock exhibit would likely be sold to become food. And the combines and tractors were mechanical beasts up close; before that day, I’d only ever seen them from the backseat car window as we drove Nebraska’s back highways.

I wandered through the public school art exhibit, hoping to find something — preferably with a fancy blue ribbon on it — done by a classmate. I fell in love with state fair lemonade, a Styrofoam cup filled with ice, sugar, fresh-squeezed lemon juice, the fresh-squeezed lemons themselves and a bit of water. For lunch, we ate corndogs at a picnic table covered in red-and-white gingham cloth, and that afternoon we wandered on to a midway carnival. In late August in Nebraska those can be brutal, and my dad decided that we’d not ride any rides, citing some concern about heat stroke and stomachs full of fair food.

Tired, hot and ready for the Beach Boys, we loitered together for an hour on the grass outside the Devaney Center before the concert. As soon as the doors opened, the Schlievert family was one of the first groups inside. (I later made a mental note never to be early for a concert, as being there first was totally lame.) We wandered the halls, scoped the merchandise for sale and begged Dad to buy us drinks and snacks from the concession stand. We found our seats, and as we waited through the sound check, I analyzed the instruments that had been set up onstage. To this day, I find something so mysterious about a drum set quietly awaiting its drummer, microphone stands with no performers behind them, a rack of guitars patient on the sidelines. We watched as the center filled with Beach Boys fans, and after what seemed like eons in kid years, the lights dimmed. Anticipation grew. And a guy with a guitar walked onstage.

He was the opening act, a concept new to me. I hadn’t expected anyone but the Beach Boys to play, and at first, I was thrilled. Two live performances in one! But I became bored after his first song. I didn’t know him or his music; all I wanted was the Beach Boys. Along with the rest of the audience, I waited through his set and then through another break, until, finally, the Beach Boys walked onstage. They smiled and waved, and the audience cheered. They knew exactly what we wanted to hear: “California Girls,” “Surfer Girl,” I Get Around,” “God Only Knows,” “Kokomo” — they gave them all to us. Beach balls were tossed around. Dancing girls in bikinis and sarongs took their places on the stage. Before “Be True to Your School” they rushed to do a costume change and emerged in cheerleader uniforms. As they returned, lead singer Mike chatted with the audience — whoever would’ve thought that, back in the 1960s when they recorded this song, they’d still be singing it today accompanied by official Beach Boys cheerleaders?

As the Beach Boys played, I thought about how happy they seemed. Whatever ugliness was in their past or darkness waited for them offstage had no presence in their performance. I looked around the audience. Folks smiled, bobbed their heads, stood and danced (even my mom, who rarely did stuff like that). Life was good. And for the duration of the concert, everything seemed perfect.

It wouldn’t last, for the Beach Boys or for us. There would be falling-outs and clashes, battles would be waged on all fronts. I would go through phases in which I would use the word “hate” to describe how I felt about my parents and siblings. I would break up a near fist fight between my teenage brother and my dad in the kitchen of our home. As adults, my sister and I would go almost a year without speaking to each other for some reason that neither of us can recall today.

But none of that mattered that night. On the bus ride home, I sat next to my mom. I rolled my eyes a few less times at the dumb jokes my dad made. I didn’t get too upset when my brother accidentally stepped on my headphones, and I even let my sister borrow one of my Rick Dees tapes.

***

This past Memorial Day, the Beach Boys, performing with only one of the original members, played a show in Norfolk. My mom and sister — the only remaining members of the original Schlievert line-up still in Nebraska — decided to go. Though it was late, my mom called me when she got home from the concert. Her voice was full of an energy I hadn’t heard in a long time. She recounted details: what she wore, what the Beach Boys wore, who all she saw that she recognized, what the seating was like, which songs were performed and in what order, how many beach balls were bounced around the audience, how long the encore went, some of the back and forth conversation between the band.

Then she told me about the two women sitting behind her. “They just wanted to sit down the whole time,” she sighed. “But I needed to stand. That’s just what you’re supposed to do! I mean, how else are you supposed dance and move around to the music?! So,” she told me emphatically, “I just stood up anyway. I’m sorry if I blocked their view, but [pause, another sigh] come on! It’s a concert!”

Every once and awhile, my mother drops gems like these on me. Like the time she asked me to make her a Beatles playlist (“Not the cute stuff, I want the good, druggie stuff from their later years”) or the day not too long ago that she mentioned she’d bought herself a copy of the original 1971 Shaft soundtrack so she could listen to it on Sunday mornings while she drinks coffee and reads the Omaha World-Herald.

I know that music has always spoken to my mom. I have too many of her old LPs to deny it. The “Kicks” track on her old Paul Revere and the Raiders album is completely worn away, and it’s possible that her Rolling Stones records have seen more action than Mick Jagger.

When my dad was alive, the two of them would listen to music together. The selection was always his, and my mom seemed to just buckle in for the ride. When he died in 2008, he took part of her with him — the part that often allows her to smile, laugh, and enjoy life. But something about the concert unearthed a bit of that in her. Maybe old Southern Californian surf and hot rod tunes are good for landlocked Nebraskans. Maybe there’s something about Beach Boys music that has that sort of power.

But knowing my mom, I bet it was something more. Maybe she was reminded of the trip we’d taken by bus as a family 22 years prior to see a similar show. Maybe she remembered watching us kids bop around in the overpriced concert T-shirts we had purchased in commemoration. Maybe she thought back to all of the car rides fueled by Beach Boys songs. Maybe she heard my dad, singing along in his not-so-good falsetto.

Like the Beach Boys, my family has a collective history that includes successes, downfalls, and drama. There have been layers of harmonies that have sometimes worked for us and sometimes haven’t. Our arrangements have been complex, our instrumentation unconventional, our methods of laying it all down experimental.

And because of this, I imagine that, for my mom, it’s impossible to separate “family” from “music” when it comes to certain memories we hold close. At least that’s how it is for me.

Chelsea Schlievert Yates is a Hear Nebraska contributor. She grew up in northeast Nebraska and now lives in Seattle, Washington. Reach her at cdschlievert@gmail.com.