Stuck about an inch from the top of my computer screen is a tiny, dead insect. For a little more than a year now, the bug has been sealed behind glass, its final resting place no more than one or two pixels wide.

Over my browser tabs, its legs are often splayed. Other times, it’s frozen over a desktop of an eastern Nebraska sunset. Witness to the digital worlds I traverse, the bug has become somewhat of a companion, and, you know, a reminder of imminent doom.

It’s to this bug — and web lovers/addicts like me — that I compare the cartooned, ethernet-for-blood-vessels audience of St. Vincent‘s most recent, self-titled record, which she bunny-hopped around on Tuesday night at Sokol Auditorium. Puppeteer and puppet of the performance art show, songwriter and frontwoman Annie Clark played the part of a lifeless, computer-bound being as she spoke to us, the last generation to make fire with a magnifying glass and the sun, before notifications encased in red swallowed our attention.

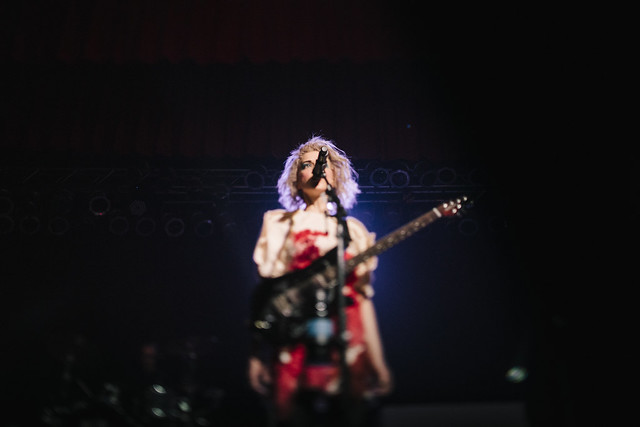

Though it’s not a leap from her earlier work, which spans three previous albums and seven years, Clark builds her criticism with the same tools that make the digital age: ostentatious lights and electronic instruments. If the cords would have been pulled, we’d have had to strain our ears to hear the picked, twhapped and keyed music onstage. Two keyboards, a laptop, a few percussion trigger pads and electric guitars comprised the majority of instrumentation. Even with amplification and a bit of acoustic drums, though, the volume never neared levels that would ring ears, even as the lights burned pinkish-purple orbs into our eyes.

At times angular and other times symmetrical, the band’s choreography complemented songs like “Digital Witness” and “Birth in Reverse.” Clark and Toko Yasuda — St. Vincent’s ambassador of “celestial voices,” keeper of the “face-ripping guitar,” as Clark put it — built metaphorical moving walkways, shuffling their feet on a stage that allowed for trips to its farthest reaches, open as ever without a single monitor pointed at the band.

Like a reimagined Madonna, Clark would writhe on the two-tiered, boxy-wedding-cake pedestal that anchored the stage’s middle during “I Prefer Your Love,” a song that folds Jesus into the losses of innocence and questions of who controls whom in St. Vincent’s discography. In other guitar-driven songs, she’d stand atop the cake and lock her knees, then type notes into her frets at speeds rivaled only by Mavis Beacon.

In the first of 20 songs, she accepted her first guitar (of three, I believe) from a tech as if it were an Olympic medal for robotic housekeeping, and she dutifully let it control her. Those notes could shred more than paper, let me tell you. And when cacophony wasn’t the intended result, Clark didn’t hide behind distortion, but rather pivoted upon precise effects that laid bare any small mistakes.

All for the service of the show, too, which yes, seemed to inherit some of its staging from Clark’s time with David Byrne, with whom she shared Des Moines’ 80/35 Festival stage last summer. A short trip around the internet affords a look at what just might be one of the most well-orchestrated and hardly shape-shifting sets on the road now. The setlist for Omaha’s concert remained almost identical to shows stemming back at least to February in New York. Clark pulled a handful of tracks from 2011’s Strange Mercy, a pair from 2009’s Actor and the set-ending, extended “Your Lips Are Red” from her debut 2007 record, as well as the body-breaking, punk barrage of “Krokodil.”

Throughout, she stitched the years together with an in-between-songs narrative that asked concertgoers to consider what we had in common with Clark: We, too, had an imaginary friend named Mercedes whom we unceremoniously killed, right? We built shrines out of the debris of beer pong cups and Buckeyes shirts. And we, too, wonder what strangers looked like as babies, she said.

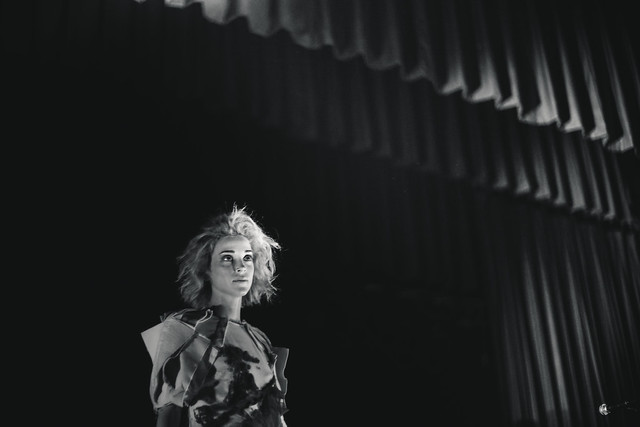

As for Clark’s look, well, of course she’s beautiful. For the first 18 songs, she wore a dress covered in what looks like a cup of blood swirling through a glass of milk, and painted her face with a ghostly pallor offsetting her blue mascara. For the final two songs, her wardrobe settled into black, squared and notched shoulders that matched the deathly quiet she willed the audience into allowing for her solo performance of “Strange Mercy.”

But although the script was poetic, Clark did break character a few times as she swiftly shoved her in-ear monitor back in her ear when it wobbled its way out. Testament to her musical aptitude, she hardly missed a note, even when jumping octaves here and there. If anything, the timbre of her voice once or twice revealed a bit of understandable weathering, now 28 shows into a globetrotting tour.

Come to think, the vocal and musical-staff-hopping gymnastics that Clark and company performed might have actually helped to fulfill the goal of the Czech Sokol movement, which helped build the auditorium St. Vincent played on Tuesday.

Is that a stretch? Perhaps. Are we the “physically strong and mentally alert citizens” the Sokol movement intended to shape? Not quite, but it’s art like St. Vincent’s that helps us hold our own feet to the fire.

And helps remind us that we can make the flames, too, so long as we aren’t afraid of them.

Michael Todd is a Hear Nebraska contributor. He became acquainted with a new friend named the Donut Stop on Tuesday. Reach Michael at michaeltodd@hearnebraska.org.