“William S. Burroughs is like a speck of dirt in your carpet: once you start looking, you see him everywhere.” – Chal Ravens

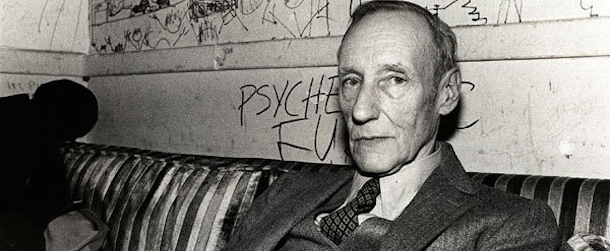

Like an intravenous drug, writer William S. Burroughs (1914-1997) pumps through the veins our collective artistic consciousness. His works — thought by some obscene, others innovative and yet others just plain weird — exposed readers to life on the fringes of American society during the second half of the 20th century: queer, doped, sexual, experimental, experiential. In his darkly comic and semi-autobiographical writing, he explored taboo subjects: junkies and pimps, prostitutes and hustlers, gay sex and sexual violence, government corruption and control. Some say he romanticized the life of drug addicts; others viewed his depictions as tragic, unhealthy obsessions. No matter how unusual or alien his work seemed, he wrote about personal indiscretions without apology and encouraged others to do the same.

If Burroughs were still alive, he would be celebrating his 100th birthday this year. Because of this, I want to reflect his impact on musicians, from international rock superstars and avant-garde sound artists to underground culture-makers and contemporary Nebraska songwriters. A fascinating, complicated and — let’s be honest — strange artist, Burroughs proved for many that was it OK to be an outsider. He also introduced new techniques for writing and sound recording that would be borrowed by musicians from the Rolling Stones to the Dead Kennedys to Sonic Youth.

I was introduced to Burroughs through David Bowie and Patti Smith (see below), two musicians I adored when I was in college (and still adore today). Who was that odd-looking old man in photos with Patti from her CBGBs days? Why didn’t the lyrics to David’s songs always make sense? The answer to both questions was Burroughs.

I first attempted to read Naked Lunch, his most famous book, the summer after college. Deemed too controversial shortly after its publication in 1959 because it depicted drug use and sodomy, the book was banned in some US cities. It was even put on trial, although ultimately the courts decided it hadn’t violated any obscenity statutes. Naked Lunch’s legacy as a forbidden, outlaw book — coupled with the fact that David and Patti cited its author as a major influence — convinced me I was totally going to dig it. But fifty pages in, I put the book down. Confused by its nonlinear structure, bewildered by the glimpses it offered into the lives of junkies and freaked out by the dark, uncomfortable images it planted in my brain, I returned it to the public library as soon as I could.

Yet, it left behind some pretty heavy residue. As Lou Reed said, “When I read Burroughs, it changed my vision of what you could write about, how you could write.” Naked Lunch forever altered my ideas about what books — and by extension music and art — could be. Why must books follow a linear structure? Who says sentences need to make sense? Why shouldn’t people write about dope fiends or read about cocks and dildos? Who’s right is it to control what and how information is received? Over the years, I revisited the book, each time delving a little deeper and learning a bit more about its author. I started thinking about the importance of transcendence across artistic boundaries. What did it mean, really, for musicians to borrow techniques from novelists, for poets to write alongside painters, for filmmakers to exchange ideas with songwriters? Until Burroughs, I thought art was supposed to be pretty and pleasurable, clearly defined and packaged in neat little boxes: music, visual, literary, performing. It never occurred to me how exciting art became when one simply disregarded or deliberately erased the boundaries between genres.

* * *

Like his art, Burroughs existed in the gray areas of society: between mainstream and counter culture, high society and the underground, the limelight and the gutter. Though he came from a well-off St. Louis family and studied at Harvard, he lived most of his life as a heroin addict, spending a good part of his adult years scraping by on the money he made from writing gigs and selling drugs. He tried to kick his habit several times and often relapsed. He spent years in the company of Beat writers like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg and struggled with coming to terms with his sexual identity. Though gay, he married twice and became a father. A lifelong gun fanatic, he shot and killed his second wife during a drunken game of William Tell. It was an act for which he was never prosecuted, though some say he served his own self-imposed life sentence. Her tragic and unfortunate death became the catalyst for him to write — he needed, he said, to address the “Ugly Spirit” within him.

Burroughs spent years on the run from the law for various drug charges, traveling from the US to Mexico, through South America, Tangiers and France. He wrote Naked Lunch while abroad, collaborating with Kerouac and Ginsberg on its arrangement and editing. Shortly after its publication, he began to gain a following. Over the next decades he became known as a cultural outlaw, someone who wasn’t afraid to question authority, who understood the rules but chose to defy them.

Unapologetic for his work and lifestyle and unwilling to conform to society’s expectations of what art should be, Burroughs embodied pure creative integrity to many: he made the art that he wanted to make. Patti Smith, a devoted follower of Burroughs, received this advice from him early in her career: “Build a good name. Keep your name clean. Don’t make compromises, don’t worry about making a bunch of money or being successful—be concerned with doing good work and make the right choices and protect your work. And if you build a good name, eventually, that name will be its own currency.”

In the 1970s, Burroughs began writing a column for the music magazine Crawdaddy. If they hadn’t heard of him already, Crawdaddy’s readers—music fans, musicians, critics and others in the industry—got to know him through his writing. Around this time, he was living a few blocks away from CBGBs in New York City and, though decades older than most of the crowd, regularly attended shows. Punks and new wave artists identified with his anti-authoritarian and anarchist views. Some say that he even prophesized the punk movement in works such as his 1971 book The Wild Boys. Joe Strummer, Ian Curtis, Richard Hell and David Byrne, as well as music critic Lester Bangs, were among those who celebrated his willingness to push cultural normative buttons and plow through barriers of—take your pick—art, social expectations, language, technique, psyche. Though he never used the term himself, he acquired the nickname “the Godfather of Punk.”

Musicians drew from Burroughs in process and technique, too. In the 1960s and 70s he began experimenting with the “cut-up method” in his writing—in which one writes text on a page, cuts up the page, and then rearranges the words to form new phrases that may or may not make sense. Soon songwriters began using the technique to write lyrics. The Rolling Stones’ “Casino Boogie” from 1972’s Exile on Main St. is a cut-up, as are many of the tracks on David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs from two years later. Jello Biafra and Thurston Moore both applied the cut-up method to music they wrote for their bands the Dead Kennedys and Sonic Youth, and Thom Yorke used a variation of it on Radiohead’s 2000 album Kid A; it is said that he wrote single lines of text, placed them in a hat, then pulled them out to form lyrics.

Burroughs was also intrigued by sound recording techniques. He created his own recordings by taping his voice then cutting and reconfiguring the tape to create a collage of word fragments: repeated and looped, stripped of their context and meaning, boiled down to their sound. Many critics regard such experimentation as a precursor to digital cutting and sampling trends that would soon transform popular music. And many musicians, to whom this technique was fresh and innovative, sought out his company, hoping to learn from him and collaborate on projects.

Through spoken word albums and audio recordings as well as cameo appearances in music videos, Burroughs moved through generations of musicians. The list of artists with whom he collaborated is impressive: Frank Zappa, John Cage, Phillip Glass, Laurie Anderson, John Cale, Donald Fagen, Kurt Cobain, Tom Waits, Nick Cave, Sonic Youth, Throbbing Gristle, R.E.M., U2 and Ministry, to name a few. I don’t know if he had much interest in the art they were making (I, for one, cannot imagine a 79-year-old Burroughs listening to Nirvana or Ministry), but he must have understood its significance and the importance of new generations of culture-makers and shakers.

Through his life, Burroughs developed quite a body of work: eighteen novels, six short story collections, four essay collections, interviews and letters, not to mention audio recordings and appearances in films and music videos. (Did I say painting? He picked that up in the 1980s, his preferred process being to shoot spray paint cans with a shotgun.)

Still, his primary life partner was heroin, and though the years brought artistic collaborations, they also brought death. He lost his only son to alcoholism, outlived most of his contemporaries as well as many artists of younger generations poised to carry the creative torch he’d lit. Just as heroin seeped through his veins, it also brought the deaths of others whose blood was polluted by it: Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Sid Vicious, Dee Dee Ramone, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kurt Cobain. It’s got to be weird to outlive your own legacy.

* * *

Next time you’re sifting through bins in a record store, try to avoid Burroughs-influenced music. It’s difficult to do. He’s the guy the Beatles placed in the dead center of the Sgt. Peppers Lonely Heart’s Club Band album cover; that’s him, standing next to Marilyn Monroe. Steely Dan, Soft Machine, the Mugwumps, Dead Fingers Talk and Clem Snide all lifted their band names from the pages of his books. Many musicians, including the Rolling Stones, Iggy Pop and Joy Division, wrote songs inspired by or in direct reference to his work (“Undercover of the Night,” “Lust for Life” and “Interzone,” respectively). Were it not for his writing, Steppenwolf would have had to call their song “Born to be Wild” something else, as would the critics who dubbed the genre “heavy metal.” Both are phrases Burroughs introduced in his 1962 novel The Soft Machine.

It’s hard for me to imagine Pink Floyd’s The Wall ever coming into existence without Burroughs, and it’s harder yet to listen to Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground’s songs like “Walk on the Wild Side” and “Heroin” without hearing him. Today he’s present in the music of the Klaxons and the Horrors. There’s even an international music collective that goes by the name William S. Burroughs Hurts. And just last year Thurston Moore’s latest band Chelsea Light Moving released their self-titled debut album, which they described as “Burroughs rock.”

Some say that there is more artistic freedom in the world today because of Burroughs Through the transgressive nature of his art, he enabled and encouraged others to more freely express themselves. Echoes of his work can be heard in those who experiment with rule-bending musical forms and unorthodox methods of lyric formation. Contemporary songwriters who look to Thom Yorke, Syd Barrett and Tom Waits for inspiration inherit some of Burroughs with every listen. I like to think about the staggering number of artists making music today who’ve absorbed his methods and ideas without even knowing it. No matter how he is regarded—as a creative genius, a junkie murderer, a rock star’s rock star—he refocused cultural and artistic queries. Under his influence, art and music became about unapologetically expressing what you wanted to express—no matter how subversive, radical, fucked up or alien.

Nebraska Musicians on Burroughs

Jeremy Holan of The Travelling Mercies:

"I first heard of Burroughs in my early 20s when I got into Jack Kerouac. I wasn't interested. At the time I identified more strongly with Kerouac: he was from a working-class family. Burroughs was a grown man living off an allowance from his rich parents. Who wouldn't be an artist if they didn't have to worry about paying their bills, I thought. Kerouac had a strong connection to his church upbringing and talked about girls. Burroughs was a godless queer. Kerouac was a drinker. Burroughs got off on dope. Kerouac dressed like a regular dude; all the pictures of Burroughs I'd seen featured him in a suit.

However, It wasn't until the last few years that I gained an appreciation for Burroughs: his perennial role as an outsider, his dark humor, his life lived with little regard to convention. He really was rock and roll as I define it. I have no doubt that much of the music I love wouldn't exist were it not for his influence.

One concrete connection he's had to my songwriting has been through the use of the cut-up technique he helped make popular. I discovered it a few years ago and started using it, not to come up with lyrics to an entire song, but to help break through writer's block. Rather than sit staring at a blank page, sometimes I'll use variations of the technique to play with words and, for lack of a less pretentious phrase, drive my consciousness off the map a ways. Mostly I find nothing usable. But once in a while, phrases will jump out that spur new ideas and songwriting directions."

photo by Chloe Ekberg

Tery Daly of The Static Octopus, Floating Opera and Magma Melodier:

"I found my way to Burroughs through other Beat writers: Kerouac, Ginsberg, etc. After getting to know their life stories, I always found Burroughs to be one of the most interesting of them, that’s for sure. He reinforced things in songwriting style that I already liked from other people, and his writing style was very attractive in the same way. By the time I started reading Burroughs, I was a big fan of a style of lyric writing now referred to as “lyrical impressionism,” in which the lyricist’s words are meant to convey an image, rather than telling a linear, clearly understood story, or even just to string together words more for their sound than any specific meaning That type of lyric writing has always attracted my attention, perhaps because it was more challenging in that you either have to deduce a meaning or provide your own, which may have nothing whatsoever to do with what the writer’s intent may have been. But it doesn’t really matter; that’s kind of the point.

Burroughs’ cut-up technique has probably made the biggest impression on me out of all his work. I like the randomness, and how the phrases created through cut-ups can mean nothing or something, or just sound nice without necessarily having any specific meaning.

A lot of my songs are written in this way. One example is “Braindolls” (from the Static Octopus’s 2005 album Here Comes Nothing), a song that literally means nothing whatsoever. It’s just a collection of weird word combinations that I liked the way they sounded."

"Don’t jump four eyes

The sunrise unseen

By emerald roof-dwellers

In mohair machines

The dying daredevil’s

Flying forever

Braindolls together

It’s an empty routine

You wear a hat like Uncle Sam

You wear a cape like superman

You swim around in a sunken sky

And disappear in the blink of an eye

Look out, cretins

Don’t fall apart

Cause insects are crawling inside of your heart

Your dustbowl desires

Are fairly obscene

Braindolls forever

It’s an empty routine."

photo by Michael Todd

Chelsea Schlievert Yates is a Hear Nebraska contributor. She grew up in northeast Nebraska and now lives in Seattle, Washington. Reach her at cdschlievert@gmail.com.