[Editor’s note: Liner Notes chronicles how Chelsea Schlievert Yates discovered music through the ’80s and ’90s while growing up in Norfolk, Neb. We hope to post a new installment every other week. Read more here.]

I received my first mixtape in 1985 at the age of 7. It was from my babysitter Amy, who lived across the street from us. Koenigstein Avenue, the street on which I grew up in Norfolk, was actually pretty quiet, given the amount of kids who lived in the neighborhood. Our house was on the north side of Koenigstein; our yard bordered that of our neighbors, the Thomases, on the left; a convent of Missionary Benedictine Sisters in the back; and a priest’s house on the right.

Two of the Thomas girls were close in age to my sister and me, and we spent many Saturday afternoons playing school in their garage, provided that I got to be the teacher. After all, I was the oldest. In the fall, we’d build leaf houses in their backyard. During the winter, I’d take my little brother and sister sledding with the Thomas kids at the convent. Bundled in attire that Nebraska winters demanded — snow pants, coats, boots, scarves, mittens and stocking hats — we’d trudge through the drifted snow in the backyard, crawl through the bushes and enter the grounds of the convent. Occasionally, a few of the sisters would come out and sled with us, if it wasn’t too cold. I marveled at how they never seemed to get their habits caught on the sled ride down the hill.

Only once did I not stay out of the priest’s yard. One spring, a few of the boys in the neighborhood had split the front wheels on their Big Wheels, and I wanted to show them I was just as strong as they were, not realizing that doing so would render my beloved Powder Puff Big Wheel totally useless. I had an idea: Thinking our clerical neighbor had left for the day, I pedaled into his driveway and deliberately rammed my Big Wheel into his garage door as hard as I could. (I knew better than to mess with with the garage door at our house; my dad wouldn’t even allow black snake fireworks in his driveway on the Fourth of July because of the marks they left. He certainly would not approve of scrapes or dents on the garage door from by my Big Wheel. But surely a priest wouldn’t care, would he?) The front wheel didn’t split, so I backed up and tried again. And then a few more times. As I approached for my fifth or sixth attempt, the priest surprised me by emerging from the house. He politely asked me to stop. Feeling scared, embarrassed, guilty and a little upset that I wasn’t able to prove myself as tough as the neighbor boys, I turned the Big Wheel around and pedaled home. I avoided the priest and his yard all together after that.

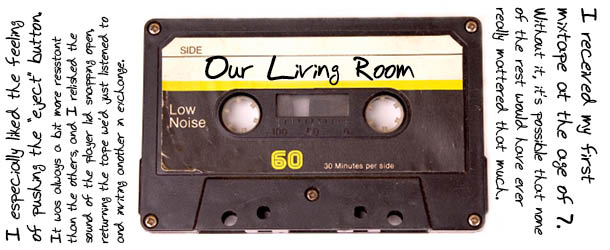

During the summer, though, the days were all Amy’s. She would cross Koenigstein Avenue and come over as my parents left for work, bringing along tapes of music she was listening to, as well as a portable tape player since we didn’t yet own a cassette player. Nebraska summers were usually too hot for outside play, and so she would set up her tape player in the living room, open the cover, slide in a cassette, shut the lid, click the “play” button, and introduce my sister and me to the cool sounds of Bananarama, Adam Ant, the Go-Gos and Duran Duran. Mesmerized, I’d watch the two spools wind the magic magnetic tape, transferring it from one side of the cassette to the other and somehow creating music in the process. I loved the hum of Amy’s tape player, and I especially liked the feeling of pushing the “eject” button. It was always a bit more resistant than the others, and I relished the sound of the player lid snapping open, returning the tape we’d just listened to and inviting another in exchange.

Our living room wasn’t terribly comfortable. It often functioned more as a large entry foyer than a room, but as it was the most centralized space in our house, it was the best place for music. Anything played there could be heard in the kitchen, dining room and bedrooms. Hidden away in the bookshelf cabinets, my dad’s record player, stereo and all necessary cords were still easily accessible — something I knew my mom appreciated on Sunday afternoons when she’d put on an old Supremes or Liza Minnelli album while she picked up the house.

Our living room was also the one room in which we kids weren’t allowed to play. The carved, wooden coffee table was from the 1860s and, though pretty to look at, was too precious to actually use. My mom’s collection of rocking horses graced the bookshelves, and some of the larger ones sidled up next to the furniture on the floor. These were especially tantalizing: They were the perfect size and shape for a little kid to ride, but because they were collectibles, they were off-limits.

I was the main reason for our banishment from the living room. Shortly after we moved into the house and my parents bought new furniture — two uncomfortable camel-covered loveseats with matching wingback chairs — 3-year-old me thought the small couches were need of some panache. I went to work coloring each of their tufted buttons with a different crayon from my Crayola box. I was halfway through the second loveseat when my mom discovered my colorful enhancements and sent me to my room.

But by the time I was 6, my parents had started to lighten up on our sentencing. This was good timing. Amy had started to sit for us by then, and we realized that the living room had the most open floor space of all the rooms in our house. After putting my brother down for a nap, Amy would gather my sister and me in the living room, despite its awkward furniture and breakables, and we’d spread out cassette tapes, carefully assessing cover art as we decided which tape to play next.

I’m not sure what music I listened to before Amy. There were songs learned in kindergarten and from Sesame Street, songs I heard on the radio at my parents’ store at the mall in Norfolk (to this day, I associate Fleetwood Mac with the Sunset Plaza shopping center), and snippets of songs my dad sang to me — among them, the Chordettes’ “Lollipop” to make me laugh and Jack Scott’s “Goodbye Baby” before he left for work.

During days spent with Amy, I decided that Duran Duran was my favorite band. It didn’t matter that the members were about 20 years older than me and that I didn’t understand what most of their songs were about. For my 7th birthday, Amy gave me a Duran Duran shirt and a mixtape, a present I unwrapped while sitting on the floor in the middle of the living room. I would wear the shirt all the time, certain that, next to Amy, I was the coolest person on our block.

But that tape. It meant everything to me. It was the only one she ever made me, but it was stellar. It included some of the best pop music that the early 1980s had to offer: Prince, Culture Club, Billy Idol, Michael Jackson, Madonna, Wham, Cyndi Lauper, the Eurythmics. My dad bought my sister and me an inexpensive tape player to keep in the bedroom we shared; I listened to my tape every night before I fell asleep. I memorized the order of the songs, and all of the lyrics I could make out. I made up baton-twirling routines to it, based on what I’d practiced in the baton lessons I’d taken over the summer. I studied MTV for news and new music of the musicians on my tape (around this same time, Amy had introduced us to MTV, and I had decided that I wanted to be a “VJ,” or video jockey, just like Martha Quinn when I grew up). I sung along with Boy George, I danced with Madonna, and I played that tape until it literally wore out.

Over the years, I made my share of mixtapes — and later, mixes burned to compact discs, and now MP3 playlists, though I’ve always referred to them simply as “mixtapes.” Some mixes lived for a while in the tape deck of the ‘87 Nissan Maxima I drove around Norfolk while in high school, others were gifted to my friends and potential boyfriends (in the case of the latter, as a means to impress and also as a litmus test: If my music wasn’t well-received, then what sort of future could we possibly have together?). I also received some good ones, too.

But the mixtape given to me by Amy, the babysitter in our living room on Koenigstein Avenue, will forever reign over all of the others. Because without it, it’s possible that none of the rest would have ever really mattered that much.

Chelsea Schlievert Yates is a Hear Nebraska contributor. She grew up in northeast Nebraska and now lives in Seattle, Washington. Reach her at cdschlievert@gmail.com.