You observed him as much as heard him.

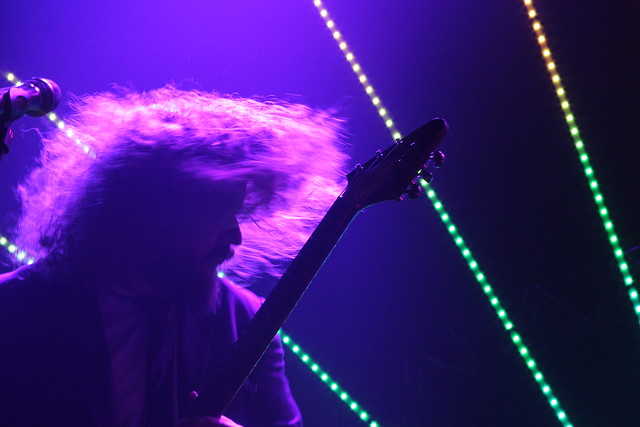

Yes, he was standing there in the burgundy suit and the pale flesh, but more as a vivid impression of a kindly, mad genius or an eccentric cult leader than a physical man. He was the anchor for the hundred specks of celestial light shooting from the centerpoint of the stage, but also the wild astronaut lost in space: unpredictable and entirely singular in the midst of a choreographed dance.

In the course of a concert for which you could’ve predicted the set list, the frenzy of hair and the spectacle of lights, he somehow sent the audience home with questions.

Namely, what in the universe was Jim James thinking about for the last two hours?

But before the service could convene, before the spaceship could lift off, Basia Bulat stood in the massive exoskeleton of James’ dormant, half-moon light fixture, using her voice to fill its vacant echo chamber.

Bulat has always been a student of gospel music (see her lively reinterpretation of the traditional hymn, “Touch The Hem of His Garment.”) But with the fresh songs from her forthcoming third album Tall Tall Shadow, the power and joy of her voice was ever-more apparent. The title track and the charango-picked performance of “It Can’t Be You” were stunning examples of tone-bending, jumping between a brash chest voice and a falsetto that was surprisingly almost as full.

In an interview with Hear Nebraska, the Toronto singer-songwriter explained the balance she tries to strike between the darkness of a song that describes a blackened, melancholy eclipse of the self and the happiness of performing “Tall Tall Shadow.” Without her live band on Tuesday, Bulat was all smiles and blushed when the audience hollered for her stripped-down new material. Running her autoharp through an effects pedal allowed for increased tremolo texture on otherwise band-driven songs, such as “Gold Rush” and “Heart of My Own.”

Monday was Bulat’s third Omaha stop in six years, though she doesn’t often tour outside of Canada and Europe. In the past half-decade, Bulat’s voice has become an increasingly independent force, soaring from concrete to rafter in the Slowdown bowl, being musical without exhibiting the artifice of forethought.

If the gospel influence of her folk songs wasn’t apparent enough, Bulat cemented the affiliation with the last selection of her brief eight-song set.

“I thought maybe since we’re all good friends now, I could do one song the old-fashioned way,” she said to the audience, setting down her autoharp.

This meant clapping, the polite stomping of ankle-high, leather boots and the naked voice on the gospel standard “Hush.”

Unfortunately, it was all over too soon. Bulat stepped on stage before the clock struck 9 p.m. and was finished by 9:25 p.m. Maybe the sheer exposure of the solo performance wouldn’t have worn well over another five songs. Maybe James’ spaceship engines just needed more time to charge. But there were at least 60 people who arrived on time to see Bulat who were left standing and waiting in the dull hum of the house music when she exited the stage early.

If Bulat was solitary and revealed, Jim James was an absolute curiosity on stage: a shapeshifter cast in the same mold as his hyper-eclectic music.

For his nine-song set (before a six-song encore), the My Morning Jacket frontman stuck closely to material from his first and only solo album, Regions of Light and Sound of God, released earlier this year. James began almost a capella with the album’s first track “State of the Art (A.E.I.O.U)” — a song that appears to be half about space age technology and half about the vowels. The song set the tone for the enrapturing patience of James’ music. One funky organ riff shouldered its first three minutes as James’ inquisitive tenor voice teased questions of humanity’s very existence.

At times, James was intimate with the crowd, sliding to the edges of the stage as if on invisible roller skates (en vogue for the prog R&B he was dishing out). He touched ET fingertips with audience members in much the same way as he sang, staying in contact as he sustained a long phrase, but then letting go as he bent and abandoned the note. He sang lines such as, “We’ve got a wise old cross/The tubes are all tied/And I’m straining to remember/What it means to be alive,” right into the faces of the crowd, not as a song he wrote for himself but as some kind of sermon for mankind.

At other times, James looked a million miles away, playing the saxophone with his back to the crowd, saying literally nothing to the audience until the encore and sometimes disappearing from the stage entirely during band jams. During “Know Til Now,” James lofted a golden bear figurine over his head and then caressed the animal in his wild beard. Think Wayne Coyne and his baby at Maha last month. Only with a bear.

Perhaps because he played Regions of Light and Sound of God front-to-back, James’ music all seemed to rise up from the same sonic soil, even if the fruits resembled strains as different as traditional Middle Eastern desert chants (“All Is Forgiven”), instrumental folk (“Exploding”) and galactic funk (“Know Til Now”).

To say that James’ solo work is retro, though, seems like a mischaracterization. The album doesn’t so much look to recreate ‘70s soul and jazz as it looks back it, digging through the haze, the influences and the emotions of what came between, collecting all the dirt and obscurity of its exploration. The result is something uniquely of James’ own imagination: psychotropic jazz played with a dishtowel on his head or madly conducting his own band in the throes of funk hysteria.

Alana Rocklin’s bass guitar was chiefly responsible for guiding melodies amid the pleasant disarray of the music. She soloed on the 14th and 15th fret of her highest string as the rest of the four-piece backing band created the fuzz and buzz and thumping.

James’ famous flying V guitar was a curious silent partner throughout the set, mounted on a chest-high stand to which James would occasionally slide over, dazzle the crowd and then prance away. Still, having the guitar on the stand established a beautiful separation between man and contraption, highlighting the multi-instrumentalist’s many talents as he casually picked up his different tools mid-song, as if on a whim.

After stretching “All Is Forgiven” into a 20-minute jam, James finished off the solo record recap with “God’s Love To Deliver” and left the stage. He returned for the encore slightly more earthly, speaking to the audience for the first time, calling Omaha a “special place” and performing the only My Morning Jacket song of the night, a solo rendition of “Bermuda Highway.”

As an Omaha-oriented treat, Mike Mogis joined James on stage for a half-reunion of the supergroup Monsters of Folk, a band that James playfully referred to him and Mogis as being in “with a couple other assholes” (Conor Oberst and M. Ward).

Mogis added pedal steel and played a snub-necked 12-string guitar to James’ songs from the 2009 album, including “Dear God,” “His Master’s Voice,” “The Right Place” and “Losin Yo Head.”

When all his band had cleared the stage, James remained behind for his final perplexing act of the night: The charismatic singer offered to let the audience touch his golden bear statue.

Like the larger experience, it may have been some untethered commentary on the nature of worship and idolatry; as in “I can make you fawn over this bear I bought at a thrift shop in Louisville and then spray painted.”

Or it may have been like touching the face of enlightenment. Only Jim James knows.

Chance Solem-Pfeifer is Hear Nebraska’s staff writer. More like Jim Jones, am I right? I am not right. Reach Chance at chancesp@hearnebraska.org.