[This story runs as part of the 2016 Good Living Tour storytelling project, thanks to Humanities Nebraska, Nebraska Department of Economic Development, Peter Kiewit Foundation, Center for Rural Affairs, Pinnacle Bank, Nebraska Loves Public Schools, Union Pacific Railroad, Viaero Mobile, Huber Chevrolet and Sandhills Energy.]

* * *

When all 17 of Sidney High School’s choirs, ensembles and solo artists earned the highest marks possible at this year’s district competition, David Mead shaved his head.

The annual tradition originated in 2001 when, in an effort to jumpstart a stagnant program, the school’s vocal music teacher promised that year’s group he would get a buzz job if the Concert Choir and Sidney Singers achieved top honors in the district contest. In the consecutive 16 years since, Mead has sported a mohawk, dyed his hair blonde and shaved numerous times, all due to, and in the name of, his students’ success.

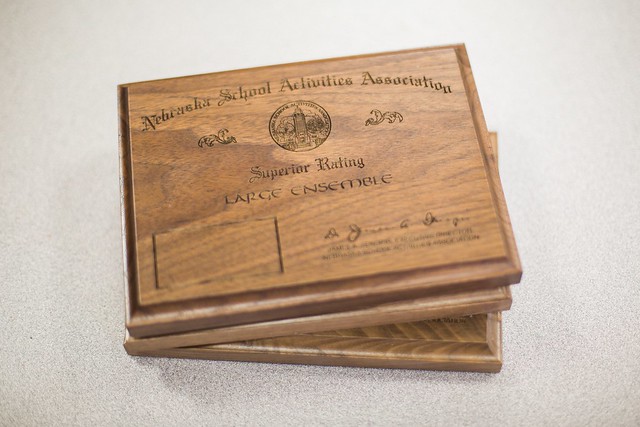

The Meads bustle about in the Sidney High School choir room one summer afternoon, sifting through the veritable inbox their office has become during a busy spring. Decades of awards line its front wall, a testament to their high-level consistency.

Even without students, their contrasting styles are immediately obvious. With David, there’s a clear, big-picture agenda. He talks about the program’s symbiotic relationship with sports and with the town and where his place is in all of it. Jennifer is his yang, honing in on the finer details: helping the soprano section nail one part of a song, guiding an individual vocalist — all of the little things that add up to a strong performance.

photo by Bridget McQuillan

David and Jennifer moved from Hyannis, Neb., to Sidney in 1996 to take on its vocal music program, carrying with them a list of implements and bountiful positivity. Upon arrival, they quickly discovered the challenges of cultivating and maintaining the accomplished choir they lead today: competition with sports, isolation from vocal music communities and budget concerns. In the constant process of overcoming them, the pair has found the right mix of discipline, detail and fun that has lead the program to 16 straight years of top honors and perennially strong program.

Together and at once, they lead a classroom guided by discipline and structure. Both grew up in military families, moving all over as children before settling separately in Nebraska. They met as vocal music majors at Chadron State College before marrying and moving on to teaching.

Thus, the hard structure is important, especially when there are eight-part arrangements or a piece in Latin or Swahili. In the same breath as acknowledging the free time creative people need to work, Jennifer points out that children crave structure.

“For many kids, not knowing what’s going to happen when they walk into a classroom is unsettling,” Jennifer says. “[Class works best] if there are routines, if there are things they can count on, if they know what we’re going to do and exactly how we’re going to do it.”

photo by Jennifer Mead by Bridget McQuillan

They have only just unpacked the district award, not yet hung because of classroom renovations (which drive our conversation down the hall to the the high school’s beautifully modern auditorium). Though this year’s district “1” extended Sidney’s streak to 17, Sidney was among roughly 13 regional high schools in contention in Alliance. Currently, there is no statewide choir competition, which ignites the competitor in David. He believes a system similar to football’s state tournament would further drive his kids — already pushed to avoid breaking the streak — to reach a higher level.

“Every other sport/activity has a statewide competition,” David says. “It makes them work a little harder when they know that, for the past three years, they’ve been beaten by this kid in speech or in wrestling … and they’re gonna work really hard to come out on top at districts.”

Sidney’s panhandle location isolates the town of 6,700 from any semblance of choir culture present in the state’s larger cities. They encounter that in the classroom on a daily basis; Jennifer estimates roughly 65-percent of their group maintains other extracurriculars.

“I think any school our size would be [in this situation], just because we compete with every other activity,” Jennifer says. “If we were in a larger school, we could have more of a choir culture because we’d have more kids that just do that.”

Instead, the Meads have created their own choir culture, testing their success more recently at a 2016 national competition at Disneyland. Not only did the choir receive a superior rating, it beat out each of the other nine participants for best choir of the weekend.

“When you do live out here in western Nebraska, there’s not a lot of recognition for your program,” David says. “To have such a grand venue like Disneyland, to have the spotlight put on them, I think everybody relished in having somebody recognize their efforts.”

photo of David Mead by Bridget McQuillan

What made that award special was the kind of choirs with which Sidney went toe-to-toe. Jennifer says many were formed through auditions, whereas Sidney High School’s roughly 400-student enrollment makes that kind of exclusivity not only impossible but harmful.

On the other hand, the positives are many. The Meads say that a good portion of their students lack the familial resources to be able to afford travel. They fundraise through candy bar and magazine sales to pay for the trip. But because any who sign up for mixed choir are admitted, it’s still possible.

And in fact, the Meads prefer their open choir policy. David believes anybody can be taught to sing, given the proper instruction on breathing and vowel production and posture. He admits very frankly that not all of his kids have “God-given talent,” but that isn’t as important as drive.

“I don’t just rely on talent,” David says. “I want the kids that can work hard.”

The Meads have instilled such a passion for the choir that those kids appear with unlikely consistency. Leaders like 2015-16 choir president Austin Jacobsen take ownership of the choir and its goals. They recall one organized rehearsal in the nearby Catholic Church.

“Dave just needed to hand in the insurance papers,” Jennifer says. “Austin did everything else. He’s always forward-thinking.”

I reach Jacobsen via telephone the same day, as he’s in Boston being carted from one Future Business Leaders of America event to another. He isn’t shy in boasting about the choir, calling it one of the best in the nation (understandably riding high from the recent big-stage success). Following the successful district showing, Jacobsen had first crack at the electric razor.

“At one point, my initials were in the back of [David’s] head,” Jacobsen says, laughing.

He attributes the cause of that success to the Meads’ toughness and persistence. The pair would push them hard, assigning a dynamic eight-part piece and drilling until it stuck.

“For an all-volunteer choir, we worked so hard,” Jacobsen says. “You have to come in each day knowing you’re going to work hard, but there’s a lot of positivity.”

David Mead sports a freshly-buzzed hair-do following his choir receiving a “1” at the 2016 district competition | photo courtesy of Jennifer Mead

With success comes hard decisions, and inevitably bigger institutions come calling. David has been courted by schools in Lincoln and Omaha with more resources and a larger student population more apt to specialize in extracurricular activities. But how strongly would their impact be felt in a larger suburban school district? The Meads don’t hesitate in answering.

“I think that the largest feather that could possibly go in my cap is to say that we have a choir [in Sidney] that can compete at just about any level anywhere,” David says.

Jennifer adds: “When you have a kid that comes to school and maybe hasn’t eaten breakfast or wears unwashed clothing, but can participate equally in a program and work to accomplish a goal, that’s rewarding.”

Jennifer’s point raises another with her husband, who recalls his family’s military history. David’s father was an army pilot who flew helicopters in the Vietnam War. He used to keep his chest of medals hidden away, not ashamed of his accomplishments but humbly, privately honoring them.

David and Jennifer’s demeanor is much the same. Back in the choir room, David has retrieved the L.A. competition trophies from his pickup and unwraps them without a word. Along with the choir’s district honors, it will soon hang with nearly two decades of hardware that proves the Meads’ success. While proud, the achievement is an annual occurrence. To repeat it requires the same humility.

“I never landed a helicopter and rescued a group of military men,” he says with admiration. “But we sing pretty good.”