A map hangs on the pale gray wall that separates the console room of The Grid Studio from its sound booth. Markings dot the United States, each a reminder of where producer Philip Zach has traveled in his past life as a touring musician.

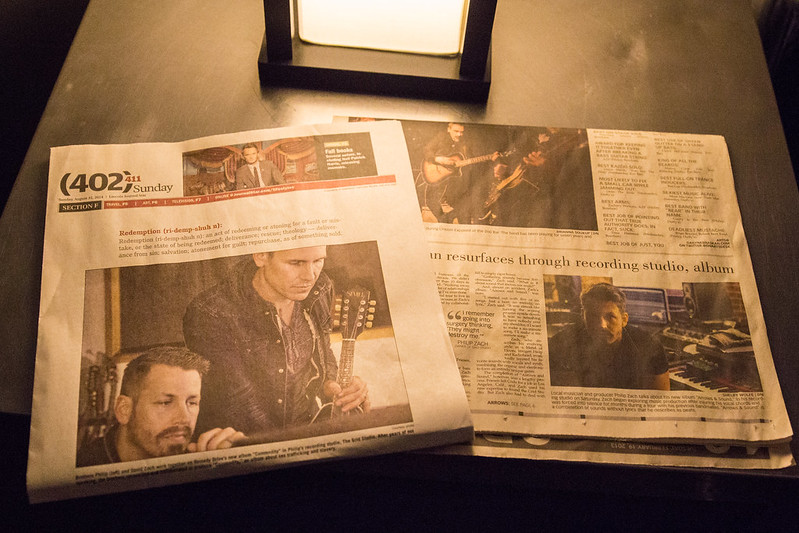

Sitting at his desk, tinkering with Pro-Tools, he looks less like he’s on the job and more like a kid in a toy store or the denizen of a warmly lit man cave. The control room is dominated by a large Apple monitor and control desk on one side, a wide leather couch on the other. The shelves are decorated with memorabilia from his old touring band, Remedy Drive, as well as his solo projects, Arrows and Sound and The Silver Pages.

Zach explains, matter-of-factly, that he will install a window into the tracking room in the exact spot on the wall where his past is charted. It will be, in a sense, a final symbolic step toward being a professional producer, with a window to his clients. On the other side of the soundbooth, he envisions another console room with a tiny vocal booth, all part of a massive planned overhaul.

The nondescript entrance to The Grid is located on 11th Street between L and M Streets in Lincoln, next door to the Hot Mess. Upstairs, most of the 3800-square foot space is now occupied by the studio, including a wide-open lobby, control room, recording booth and lounge.

Since opening The Grid in November 2011, Zach says he’s tried to create a comfortable environment conducive to experimentation for himself, and a positive place in which artists can thrive.

It’s a cozy space, one that has hosted a variety of musical artists: from Nebraska singer-songwriters Ally Rhodes and Brian Vranicar to Ireland’s the Kid (aka Kyle Graham) to classical musicians to rock bands like Minneapolis’s American Youth.

On this day, Zach is working on his aforementioned solo project Arrows and Sound. He puts on his 2013 song “What If”: Passionate tenor is punctuated by throbbing percussion and pulsating electronic notes, smoothed out by an underlying atmospheric element. Whether the ideas he chases click or crumble, Zach unabashedly geeks out over the complete control he possesses.

“I’m feasting on creative collaboration and the beauty of … sitting down and making something that nobody has ever made before,” Zach says. “Stumbling into this soundscape that nobody has ever stumbled into before.”

He’s achieved unique sounds using unconventional means, like the whoosh of his hand against the carpet, a metal drawer shutting, or his hands tapping on a custom made percussion box. Assembled using an empty cigar box, a P-90 guitar pickup, and multiple surfaces, it provides a variety of percussive sounds that Zach can then manipulate. He often runs the box through a Kaoss pad.

“I was increasingly dissatisfied with traditional band set up,” he says. “Bass, drums, guitar, piano. It had been done so many times.”

He also applied his unorthodox mentality to guitars and other non-percussion instruments, shredding individual tracks and then repackaging them. Still, he never thought he would eventually be on the other side of the glass.

“I never wanted [this] job. I wanted to be a musician, and I wanted to perform,” Zach says. “The cyclical energy of an audience … there’s something about that that is so inspiring. I didn’t think that anything else would make me feel that way.”

* * *

Philip Zach was 15 when he and his brothers formed Christian rock band Remedy Drive in their native Omaha. From that point on, writing, recording and playing shows was life, taking priority over everything else. They toured regionally over long weekends. They would play fifteen to twenty shows in the South and the West Coast over holidays from school. They were fixtures at summer Christian rock music festivals like Lifelight in South Dakota, Alive Festival in Ohio, and Rock the Desert in Midlands, TX.

“It became the thing that I thought about the most … something that I was doing more often than I wasn’t doing it,” Zach says.

He dropped out of college at 21, and Remedy Drive began a streak of ten years touring for as many as 280 days, playing 27 or 28 shows some months. Between writing an album every two years and touring relentlessly, age 31 arrived very suddenly.

“You’re in a different city, different venue every night, so you’re not thinking ever about the weekend or about the end of the month. It’s all just the same.”

Zach says that the flow of their grueling tour schedule helped forge his path to producing music. He and his brothers divided non-musical duties amongst themselves, including booking, merchandising, interviews, updating social media and driving the bus.

Once they began making records, he became fascinated by the process of recording and manipulating sound. Remedy Drive recorded six albums independently before signing with Word Records, a Warner Brothers subsidiary, in 2008. While their signing brought some positives — better distribution and professional music videos — it also introduced them to the pitfalls of recording with a major label.

When they would turn in music to their label, executive opinion was handed down from on high, down through Artists and Repertoire (A&R). A&R would go to band management, who would finally communicate directly with the band.

“There’s all these really important creative decisions that are being taken from us everytime we work with a producer,” Zach says.

When he finally found his way into the control room — during his eight-album run with the band — it was almost out of necessity. A rift had grown between he and his older brother and Remedy Drive frontman David that was nearly beyond his repair, as they fought about every single decision or detail in the direction of the band. According to Philip, even the simplest of decisions became monumental. Conflict centered around him and David, at times forcing their brothers — drummer Daniel and guitarist Paul — to choose sides, further driving a stake into the heart of their relationship.

“We were on the road 280 days a year,” Philip told the Lincoln Journal-Star on August 30, 2014. “If something bugs you one day, every day is the same. One day, it became too great.”

Their 2010 appearance at Life Light, a heavily-attended Christian rock festival in South Dakota, highlighted their struggles. The two brothers fought before, during, and after playing to the largest crowd of their lives. What should have been the seminal moment in their music career turned into a disaster marred by their irreconcilable differences, a microcosm of how great things were on paper and how toxic they had actually become.

“Even when we’re playing for that many people, and we’re signed to a record company and we’re living our dream, playing for hundreds, sometimes thousands of people every night,” Zach says from his leather control room chair.

He still seems mystified, explaining the old questions as though they posed in the present: “Why can’t we get along? Why can’t we fix this?”

In January 2011, Zach walked away from Remedy Drive. Simultaneously, another concern arose in the form of Zach’s ailing voice. He says that his handling of the high-pitched vocal parts had caused damage to his vocal chords that could only be repaired surgically. Anxiety crept in as the doctor explained the risks of such surgery.

“I thought it could be it for me, musically, at least using my voice,” Zach says.

For two months, he couldn’t speak. He felt alienated by his inability to communicate with others. Sometimes he could feel their apprehension at having to interact with him.

“People [thought] there was something wrong with me,” Zach says. “All of this stuff surmounted into this cloud of depression and anxiety and fear.”

* * *

That’s when he was approached by his friend Riley Friesen at Coda Record House in Lincoln. The studio had been operating for a couple of years, and Zach had always referred bands that he had met on the road to the recording studio. He immediately began work at Coda Record House upon leaving Remedy Drive. The two would record from 9 a.m. to 2 a.m. the next morning, working on clients projects all day. When he started Arrows and Sound in 2011, he’d record and produce his then-new solo project after midnight.

He relished the opportunity to focus intensely on recording, having complete control of the process for his music and digging in when recording others.

“I learned so much,” Zach says. “Instead of recording every once in awhile over a year and a half, recording all day every day.”

His studio work filled a void previously occupied by touring and playing music, but it was also a complete reversal from how he wrote with the band. In contrast to writing rock music by committee, producing put Zach in the lone driver’s seat.

Along the way, Zach purchased equipment to build his own setup within Coda Record House. When Friesen left for California, transitioning into his own studio made sense.

The transition from Coda to The Grid was seamless, he says, but immediately backtracks, pausing a moment to reconsider.

“I panicked a little bit [at first] because I didn’t have clients lined up, so it’s kind of survival mode.”

To make ends meet initially, he supplemented many of his clients’ projects by handling their design and photography.

When considering his own approach, Zach is reminded of the most influential producer he encountered in the Remedy Drive years, the Grammy-nominated Shaun Shankel. The band split up before they could record an album with him, but his intake approach stuck with Zach. He asked Remedy Drive about their musical tastes, their influences and what they had been listening to in an effort to understand their direction. It’s that holistic approach Zach attempts to recreate each time an artist walks through his doors.

Contrast that with their indifferent major-label engineer, who didn’t know the names of any of their songs three weeks into their sessions, and possibly hadn’t even listened to the band prior.

“I realized that, to be successful, not even just for success financially or whatever, but to really be successful making quality music, my relationships with [artists] have to be such that they trust what i’m doing, and I have to trust what they’re doing,” Zach says.

In 2013, Irish electro-pop singer The Kid, aka Kyle Graham, reached out to Zach about recording at the Grid. They clicked immediately. The two had met long ago while Zach was on tour, and Graham kept track of Zach through Facebook.

“Every time I listened to the material Philip was producing I just had that gut feeling that it was the right place for me to be,” Graham says.

Zach chuckles, almost in disbelief, when he talks about how Graham reached out to him initially.

“He sent a message and was like, ‘Man, you’re the only producer for me,’” Zach says. “It’s crazy to hear that, you know?”

Graham left Lincoln after three weeks with an entire EP in the can, where only a couple of songs were originally planned.

“Once we had nailed all five tracks … we decided that we should just write a new song together,” Graham says. “That song turned out to be my single, “Heartbeat.” I’ll never forget the process of writing that song and how much fun we had recording it.”

Zach extended his courtesy outside of the studio as well, which has become commonplace for him. On breaks from recording, Graham would pal around with Zach and his wife, going to European Motorcycle night in the Haymarket or joining the couple for dinners at their nearby home. Graham even tagged along for their anniversary date.

“He was just a part of our lives for three weeks,” Zach says. “He was just integrated into everything.”

Zach says that his 15 years on the road has helped him the ability to relate to touring bands especially.

“I’m sitting in this chair, and four guys are here from Oregon or Washington or Kansas or North Carolina or wherever they come from,” Zach says. “I can see issues that they’re going through, from things that they say to hearing them talk about shows, or seeing them relate to each other in the studio.”

As a self-taught producer, Zach admits he’s missing some of the technical knowledge. Every new recording artist presents a new challenge and a new opportunity to learn.

“That’s probably where I’ve grown the most, but where I have the most growing to do,” Zach says. “I heard a great musician once say, to be a good communicator in music, you really have to speak the language … I have to know the language of it. But at the same time, there’s just an instinctual thing that I don’t wanna lose.”

* * *

Zach flips through the hundreds of files on his computer. He looks for an example of a song for which he wrote parts during production. He cues one up: “Deadbolt,” a pop tune by Omaha native Ally Rhodes.

Zach helped write her album with Rhodes in studio, a fact easily surmised at the sound of his signature manipulated electronic rhythms. Rhodes would sit on the couch behind him, Zach explains, listening intently while he mixes tracks. She would pipe up to offer criticism if she felt a sound was unfulfilled. Can that be in a bigger cave or something?

“It [was] so fun to work with her in that way because I’m just exploring, and then sometimes she’s exploring with me,” Zach says.

For the past couple of years, The Grid has made its living on Zach’s ability to write and track instrument parts for many of the artists that pass through. While that stimulates him for his own work, a reprisal of his days as a recording artist, he would rather produce for bands that have found their sound.

“I’ve found that … [I’m] generating a lot of creative content instead of refining existing creative content,” Zach says. “I wanna find what’s there [in a band] already and finetune it.”

That band could be Lincoln’s AZP, with whom he has already collaborated. Vocalist and keyboardist Zachary Watkins lent his voice to Silver Pages, as well as percussion on Arrows and Sound. They offer high praise for each other.

“He’s a perfectionist,” Watkins says. “Whether it’s big heavy drum mixes or thick melodic harmonies, every record is precisely designed to inspire and motivate the audience.”

AZP seems to fit Zach’s vision of a group with an established, yet constantly evolving style. Both he and Watkins believe they would match perfectly.

“With Philip’s production skills and AZP’s style and musicianship we both know it’ll be something special,” Watkins says.

Zach says he’ll work with any singer/songwriter or band, though, if it tests his limits. He finds it soul-stirring to create undeterred by the boundaries of a feuding band or a suffocating record label.

“If sounds can [arouse emotion], if this thing that we hear through our ear, goes into our brain and makes our soul feel, thats just fascinating to me,” Zach says. “As we’re chasing these sounds, I try to push that path as far as it’ll go.”

Most importantly, the studio was the vessel which guided him and his brother David back together. In 2014, David, still fronting Remedy Drive, traveled to Lincoln to record Commodity, a record informed by his time rescuing sex slaves as a part of nonprofit organization Exodus Road.

It’s about hardship and hopelessness, freedom and redemption.