Start with a line from “Desert Island Questionnaire.”

It’s the penultimate track on Conor Oberst’s new album Upside Down Mountain, and its writer was playing it Wednesday night in Omaha at the Sokol Auditorium with Dawes — as the opener and backing band.

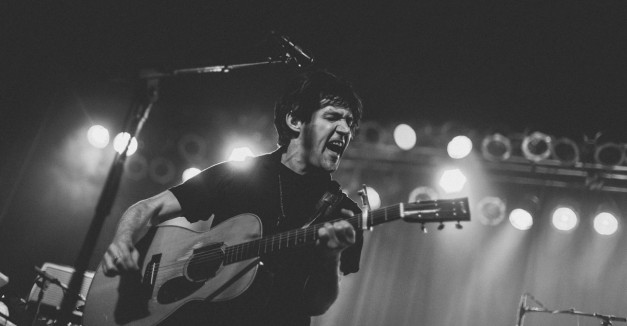

In the third verse, Oberst is lyrically destroying a Midwestern murderer and the odd religious complacency that follows his killing of a young girl. He sings: “Every lunatic must be well-intentioned, sets himself apart, he’s an instrument of God.” The verse wages a small battle on the pathology of crazy people and the victims who accept that pathology as celestially decided. Immediately before Oberst takes on the voice of the surviving mother in the song — “I know the good Lord has a plan for all of us” — he bursts into mimed action, something he did all night.

Now, there is no moment where he warns the crowd, “Hey, I’m going to speak in another person’s voice,” no disclaimer of narration. Instead, he rolls his eyes into the back of his head, scowls and double times the sign of the cross over his body. The irony is intelligent, impassioned and venomous.

But when the words escape his mouth, bolstered by rock guitars and a drum fill, the crowd is elated. How exactly the audience takes the sarcasm is conjecture. But people rarely cheer for cosmic irony like the Dropkick Murphys are making a surprise appearance at their local watering hole.

The Sokol show was like that — the poet screaming at the pep rally. Both of them riling each other up out of some common experience, some common misunderstanding.

All volatile, odd vignettes. You could eavesdrop on a people’s history of Conor Oberst in the crowd beforehand, yelling about where they’d seen him publicly during the last ten years, a mockable six degrees of Omaha separation. When Oberst came out, he wouldn’t look at the crowd. He gazed deep into the inside of his eyelids, cross-eyed at his microphone and looked sideways off stage. But not at people of Omaha.

To start, the energy was neurotic to the point of rage. Oberst looked feverish, possessed, coughing a little after “Time Forgot” and “Zigzagging Toward the Light.”

Then, he was happy to be there with “friends” and playing “Bowl Of Oranges” from the 2002’s Lifted, one of many Bright Eyes song he dusted off including “Old Soul Song,” “Poison Oak,” “Hit The Switch” and “Traveling Song.” In some ways, it felt nostalgic.

But, then he’s about to play “We Are Nowhere And It’s Now” and says it’s a song about purgatory, something he says the crowd might know something about.

“You live in fucking Omaha.” It’s witty, of course. But it’s not encouraging.

But then wild applause again. Who cheers for purgatory? What sort of identity is loudly agreeing with someone who, in that moment, said you didn’t have one? But Oberst, these days, has a new identity himself.

Upside Down Mountain is a songwriter’s record with melodies that define song structure and the lyrics of oncoming middle age that flow easily. They are not hard-bitten, they come out of a 30-something paranoia about maturity and untrustworthy, successful friends and the inevitable acceptance of those things in the end. Singing songs like “Artifact #1” and “Enola Gay” on Monday channeled the violent spirit of neuroses into keen observation.

So it’s a dissonant and eerie exhibition when Oberst returns to the scene of a written crisis and the crowd screams like the crisis is a birthday party they wait to celebrate each year.

Dawes’ effectiveness in the songs was varied across the board. They were a more glimmering substitute for the Mystic Valley Band on “Moab” and “Danny Callahan.” In many ways, the Bright Eyes songs (the uplifting “If The Brakeman Turns My Way” notwithstanding) were too ragged and raw for the sheeny guitar band to confidently flesh out. There were moments when Oberst felt like he was running away from the vocal harmonies of Taylor and Griffin Goldsmith (the brothers singing in the place of the First Aid Kit sisters on Upside Down Mountain). And Oberst’s first switch to his massive, big-bodied Stratocaster, with some of kind of bullish bass effect on it, turned the pop bounce of “Kick” into a sunken piece of shipwrecked American anger.

But on a song like “Hundreds of Ways,” Dawes engineered candied brilliance, hoisting up the tropical patio bounce of the song about just finding a personal strategy for pulling through — a general but direct antidote to the feelings of many of the songs he played from I’m Wide Awake It’s Morning.

In contrast to Oberst, when Dawes opened, frontman Taylor Goldsmith’s words seemed to wake him up. He’s the sort of songwriter whose lyrics either outlive or exist independent of the person singing them, or they withstand that illusion anyway. He sings like he’s testifying before a courtroom or giving an after-dinner speech. At its best, this takes hold in songs like the set closer, “Most People,” in which they land like real-time indictments of character flaws via drawn-out flowery metaphor —“Like January Christmas light under billion year old stars, she comes up with more of what is lost than what is found.”

That’s the Goldsmith smackdown. And he goes from unchallenged to stimulated while he sings it.

But few Conor Oberst songs can escape analysis under the pretense of just one person living life wrong and then another singing about it. Even when they’re personal, they’re political. Sadness and anger are tied to intelligence to mistrust to Midwestern flatland to anti-dogma, to the fact that that’s a dogma, too. Onstage, those implications play themselves out — a Nebraskan who appeared for those two hours that he had an adversarial relationship to the people a few feet in front of him. He sneers and they cheer. He crowd surfs. The band blasts the doors off “Roosevelt Room.” And then it’s over. Emotional confusion abounds.

It’s the dissonance of watching a paradox hover over a homecoming concert, two different ideas of what that means. A man in center-front of the stage was screaming “Conor!” as though the artist needed (and more importantly, as if he somehow wanted) a reminder of who or where he was.

Seconds later, Oberst is chomping on, and then spitting out the lyrics of “Zigzagging Toward the Light.”

“Home is a perjury, a parlor trick, an urban myth.”

Chance Solem-Pfeifer is Hear Nebraska’s managing editor. Reach him at chancesp@hearnebraska.org.