If you coax Bud Comte past saying he simply stumbled his way through starting his own record studio, label, and engineering hundreds of LPs, he’ll make it around to the good recording tales. The ones involving garden hoses.

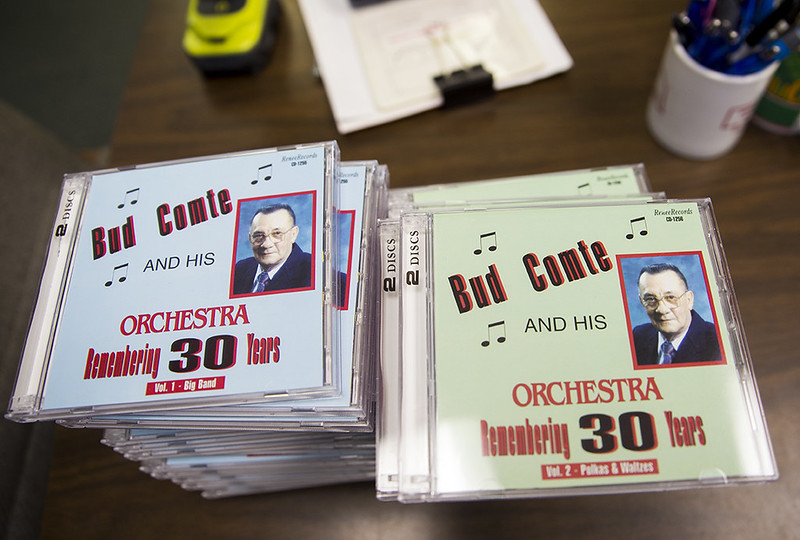

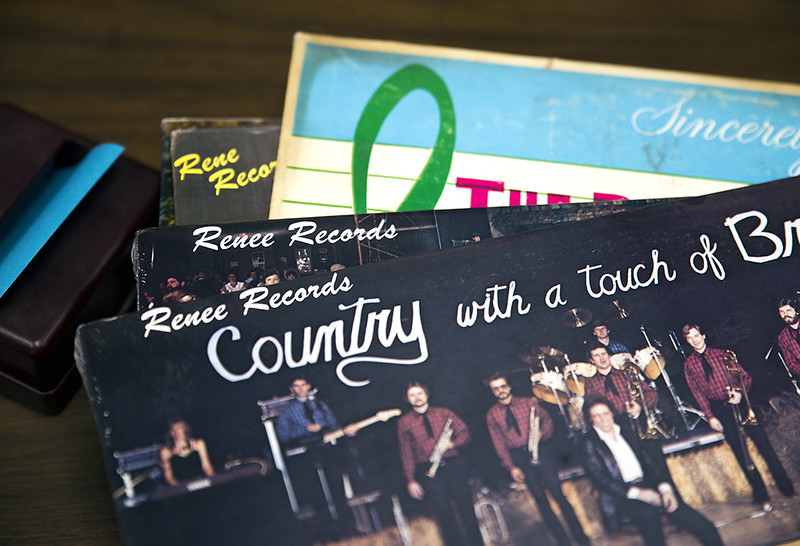

Comte was a skilled trumpet player and big band leader for decades, but when it came to owning and operating Renee Sound Studio in David City, Neb., the lifelong hobby grew with an air of whimsy and experimentation.

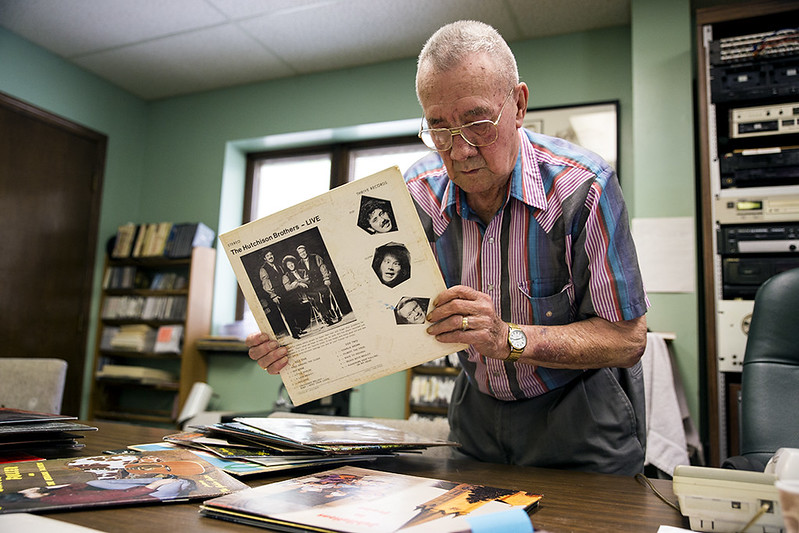

In the ’60s, Nebraska country/folk singers the Hutchinson Brothers recorded an original song — Comte wryly remembers it being called “I Got Love Bubbles In My Tummy” — and asked their engineer for bubble sounds. The brick studio was outfitted with a Fostex 16-track tape machine, and no opportunity to digitize such an effect. So Comte spent two hours attempting to record bubbles with a garden hose, bucket of water and a microphone with an inflated condom attached to it.

“It worked great!” the 83-year-old Comte says, sitting on a speaker in the main room of his studio last month.

“How did you know that would work?”

“I didn’t!”

He’s chain-smoking, letting ashes fall onto the studio floor. His studio floor.

He recalls another time when he wanted a reverb effect, in the days before it was possible without using plate reverb. He wrangled 50 feet of garden hose, coiled it on nails around the studio, stuck a funnel in the front and mic’d the other end.

“How it possible both of these stories involve garden hoses?”

“I had one hanging on the wall!”

With Comte perched in the middle of it, Renee Sound Studio is in a state of generational and technological flux. The analog equipment will be put on Craigslist soon, and to Comte’s left, his son Ryan is in the process of erecting a small digital rig. The room is wood-paneled and shag-carpeted, entrenched with decades of cigarette smoke that’s so deeply absorbed it hits the throat before the nose. Behind Comte is what Ryan calls “The Bud Comte Shrine,” a posterized cover of one of Comte’s big band albums, this one live from the Grand Island reception hall, Liederkranz. He looks like a young, but more army-ready, Edward R. Murrow.

At this moment, the room is a visage of dark 20th century authenticity ramrodding kitsch. The cherry red Beats by Dre sitting by the computer rig only prove the obsolescence of a Nebraska music idiosyncrasy: a 2,500-person town that wears its recording studio right out on its highway entrance, like a welcome sign.

As he recounts stories of his studio and the subsequent label, Renee Records, Comte fixates on the line, “… and that’s a true story.”

He roped together his first 8-track recorder from two four-track players when Nebraska polka bandleader Ernie Kucera wanted to record with him.

“I started buying stuff and forgot to quit,” Comte says. “True story.”

The quip hints at Comte spending many years around tall tales, recording country musicians who hoped to make it big and playing cards on a bus with his touring orchestra. But it also points back to the unlikelihood that such a place would exist in a small Nebraska town, an unsuspecting place where Comte has worked at his feedlot most of his life. Not much is subject to change in such a place, so the idea that a tinkering amateur sound engineer would release a few hundred records might raise a few eyebrows.

A Springfield, Neb., native, Comte came to David City when he was 17 to work construction. He’d started playing trumpet his freshman year of high school. Seven lessons in, his instructor committed suicide. Another “true story.” After serving in the Korean War, he played his first David City gig as the bandleader of Bud Comte and his Orchestra in 1955. The band toured only regionally, but in endless circles, clocking an estimated 175,000 miles on the road in its 30 years of existence.

Comte began recording demo tapes out of his family’s basement in the early ‘60s. When the Comtes decided they no longer wanted blankets hanging on the walls of the house, they moved the studio to the garage in 1967. The breezeway between the house and garage became Renee’s small control room.

With the names Comte recorded the next 30 years, you’d have more luck perking up heads at Central Nebraska barbershops and watering holes than finding them online.

It’s largely country and polka, though the ‘70s saw Comte recording rock ‘n’ roll, as well. Graham James was one such artist, whose music Comte admits he didn’t care for. The taste problem is one any working engineer faces, but Comte remembers he smiled a lot and tried to be polite. People like Dick Allison, the noted Nebraska country singer and Grand Ole Opry player, were far more his speed.

A ledger in Comte’s office charts the decades’ projects, as well as the label’s name change from “Rene Records” to “Renee Records.” The label was originally named after Comte’s daughter, but he was misinformed about his daughter’s legal culpability if anything ever went awry, so he dropped the “e.” When everyone pronounced it “reen,” he changed the spelling back again.

With stories like this, there’s still something youthful to the irreverence of how Comte talks about the decades he poured into the studio, not unlike how bored teenagers would start a punk label in their quiet town.

“I thought you had to have [a label],” Comte says, shrugging at the idea that they somehow wouldn’t have released all the music they recorded.

Before it was Renee Sound Studio, the sturdy brick cube was a blacksmith shop for the sculptor Floyd Nichols, the posthumously famous WWI knife maker. And though it sits on the highway coming into David City, its density has blocked out decades of extraneous noise from passing cars and trucks. Ryan proudly recounts the time a drunk driver even slammed into the structure, only dislodging one small chunk of the exterior wall.

“It’s built like the proverbial brick you-know-what-house,” Ryan says, explaining how the building was originally fashioned from old curbing that the WPA tore up in the 1930s.

Ryan was nine when they converted the studio from town’s old Dairy Queen, a time when he certainly had no perspective on his forthcoming lifetime of playing drums and recording bands, even a decade after his father did his last session in the early 2000s.

“Like always in life, you don’t realize how cool something is at the moment,” Ryan says. “It was an amazing experience in hindsight. I’m sure that’s why I’m still playing and trying to record, having been exposed to it. Like it’s inbred almost.”

In his twilight years, the elder Comte still clocks time at his feedlot every day. That’s been a constant, even when he would record bands until 4 in the morning. He’d be up at 7 the next day, regardless.

“I wouldn’t have all this if it wasn’t for the feed mill,” he says. “I went to work every morning. I never missed a day of work.”

After the dissolving of his band in 1985, Comte played the trumpet for the final time in 1998 at a reunion show, and hasn’t picked up the instrument again. He says it’s not much fun to play without his orchestra, members who had either moved on or passed on.

Behind Comte’s deep-set brown eyes, which do everything they can to swallow his pupils, there is a very apparent way in which his stories reside in an accumulating past: in crates of vinyl in his office or in how he introduces most every person he mentions by clarifying whether they’re still alive or not. The relationship between David City and the studio, Ryan says, is something that people who’ve lived there for 20 years or more would be much more keen to talk about.

Still, if he’s traveling and mentions David City, the question might come up:

“Isn’t that that town that has that recording studio in it?”

His father interrupts.

“I’m just a damn old fool who didn’t have any sense but to try it. That’s as well as I can tell it.”