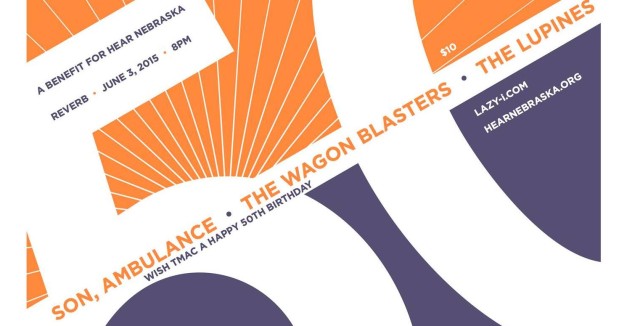

[Editor’s Note: Our thanks to Jon Taylor (Mercy Rule, Domestica) for writing this story, which previews Tim McMahan’s 50th birthday show Wednesday at Reverb Lounge. RSVP here. Son, Ambulance, The Lupines and The Wagon Blasters will perform. It’s also a benefit show for Hear Nebraska, of which McMahan is an active board member. ]

* * *

At $295, the folding aluminum coffin trolley was out of my price range. So was the pair of $250 pendant lights from the 1960s and the deadly-looking space rocket sled for $125.

Maybe the antique shops in the Old Market weren’t going to be the best places to find a good deal on an old token for an old friend. Fortunately, my recipient-to-be, who was supposed to be helping me shop, kept gravitating to the used record bins, where vinyl treasures could be had for only a dollar each.

I’d driven to Omaha to give music writer Tim McMahan a 50th birthday present, and in exchange, take from him insights on covering southeast Nebraska’s music community for almost 30 years. Given how much he has written about our scene, I doubt a fair trade would be possible.

photo by Jon Taylor

I met McMahan in 1993 as he was climbing into our band van. Wanting to experience a little bit of the touring life, he and a photographer tagged along with Mercy Rule on a trip to Iowa. The next 12 hours were filled with rock band philosophy, musical triumph, automotive failure and vomit. An excerpt:

“Photographer Mike Malone and I had no idea what we were in for: We wouldn’t be allowed to ‘take a pee,’ we’d be poisoned at a local spaghetti restaurant, and we’d be stranded in Des Moines all night, learning about the joys of Flying J truckstops and getting a crash course in auto mechanics.”

That story is one of thousands McMahan has told since he began reviewing records in the late 1980s while editor at The Gateway, UNO’s student newspaper. His graduation from college in 1988 came at about the same time he advanced to writing band interviews and show reviews.

He confesses to enjoying the free merchandise bands and labels sent his way just as much as the actual writing — at least initially. But because promotional CDs or the occasional complimentary ticket typically were the only payment McMahan got for most of his efforts through the years, his role as a music journalist has always coexisted with his long-time job at Union Pacific Railroad, where he now manages online content.

* * *

How to get Tim McMahan to listen to your band and maybe even go to your show:

- Schedule your contact with him to coincide with an upcoming Omaha performance. This, he says, gives him a reason to pick your band out of the pile. “I get tons and tons and tons of stuff in my email every day,” McMahan says. “You can’t possibly listen to it all. There’s not enough hours in a day.”

- Send him vinyl. He says he knows it is expensive to make and costly to ship, so the extra effort gets extra attention. “I can promise you that if you send me vinyl I’m going to listen to it. I don’t care who you are.

- McMahan does not write about bands he doesn’t like. Don’t take it personally, he just might not be into your sound. If you force the issue, he may relent, but remember, the guy is a music critic, not a cheerleader. “If everything is good,” he asks, “what isn’t good?”

* * *

Being a part-time music writer does not pay the rent, McMahan says.

“I did it because I enjoyed it. There are people who think I just do The Reader for a living. They’re always surprised to learn I work someplace else.”

McMahan has been covering local music so long he divides his chronicles by time periods: the Golden Age (1990s), the Saddle Creek era (2000s) and the Post Saddle Creek era (2010s-now). It’s that longevity, rather than any individual writing accomplishment, that he says he is most proud of.

“I don’t think anybody has consistently provided a thread of criticism — and can write the story of what’s happened here since the mid-90s — and is still doing it,” he says.

His account of the “Golden Age” depicts a musical storm perfect for the creation of a rock journalist. As a fan of what he called “unpopular” music, he had an ample supply of productive local bands to cover and venues like the Cog Factory, Captiol Bar and Sokol Underground in which to see them. All he needed was an outlet for his stories, so he reached out to a Lawrence, Kan.,-based publication called “The Note” with an offer to be their Omaha correspondent.

“It just so happened that the style of music I liked was the kind of music The Note covered — which was ‘college music,’” McMahan says.

“Golden Age” bands, like Mousetrap, Sideshow, Ritual Device and Frontier Trust get their designation, McMahan says, because they were some of the first groups to produce independent music and promote it primarily by touring.

“These bands were getting out on the road and spreading their Nebraska goodness throughout the U.S.,” he says. “They provided the influence and inspiration for the next generation of bands that would end up signed to the Saddle Creek label.”

Although “Golden Age” bands were successful at touring, McMahan said, they rarely sparked any national press other than alternative music magazines, such as Option or Raygun. Saddle Creek-era bands made their mark differently, he says.

“Within a few years, Saddle Creek’s crown jewel bands, Bright Eyes, Cursive and The Faint were pulling in national press from non-music publications like the New York Times, Time, Newsweek, and late-night TV (The Late Show with David Letterman) began to notice Conor (Oberst),” McMahan recalls. “Suddenly, Nebraska was getting the attention it deserved and was being called ‘the next Seattle.’”

Bands on the Saddle Creek label might have garnered the most national attention during that era, but they made up only a small fraction of the local music scene. Proof of that is found at McMahan’s Lazy-i website, where I counted around 360 stories posted in an archive called “The First Decade” (1998-2010). The variety is significantly more vast and the writing far more informed than you’ll find in any mainstream publication.

You won’t have to scroll too long before you find a familiar band or maybe even one of your favorites. His interviews include every essential local band at the time, from Criteria to the Bombardment Society and national artists like Fugazi and Dick Dale. Yet, despite the similar subject matter, McMahan’s stories are as distinctly different as the personalities of the artists he talked to. The 2007 interview with Oberst about an upcoming Bright Eyes tour is epic, comprehensive and revealing, while the story from the same time period about Little Brazil provides a gritty snapshot of a band trying to survive.

Although the internet makes it easy to follow McMahan’s narratives of the current musical landscape, it also provides a barrier, he says, because of the fierce competition for eyeballs on Facebook and Twitter. But like his favorite musicians who are also fighting to avoid being buried by the information avalanche, McMahan has faith people will find him.

“The music I write about isn’t as popular anymore. I’m lucky if I get 150 people to read [Lazy-i] a day,” he says. “I don’t have any intention to stop — I’m enjoying it too much. It’s like, ‘When am I going to quit going to shows?’”

(Likely never, McMahan assured me.)

“Either you like my style of writing or you don’t,” he continues. “Maybe you’re reading it because it’s fun to read every day, or you like the bands I’m covering, or it’s consistent. Maybe it’s something you can depend on because I write every day.”

Had we kept shopping, I’m confident something would have caught McMahan’s eye and maybe even been attainable with the $20 dollar bill in my pocket. But would it have been as dependable and impartial as McMahan’s service to music journalism in Nebraska? A set of encyclopedias? Vintage maps? Punk rock 45s?

It turns out that the best gift for someone who has devoted a few decades’ worth of words to our musical dreams might be to turn the tables Wednesday night and send a few appreciative observations his direction.