by Casey Welsch

Fistfight. Disaster. Performance art. Indecent. The Shanks have their own blood- and sweat-dripping meanings to all these terms, which have been used to describe their former sets. These punk deconstructors out of Omaha’s near past were loud, violent, abrasive and a hell of a lot of fun to watch break down.

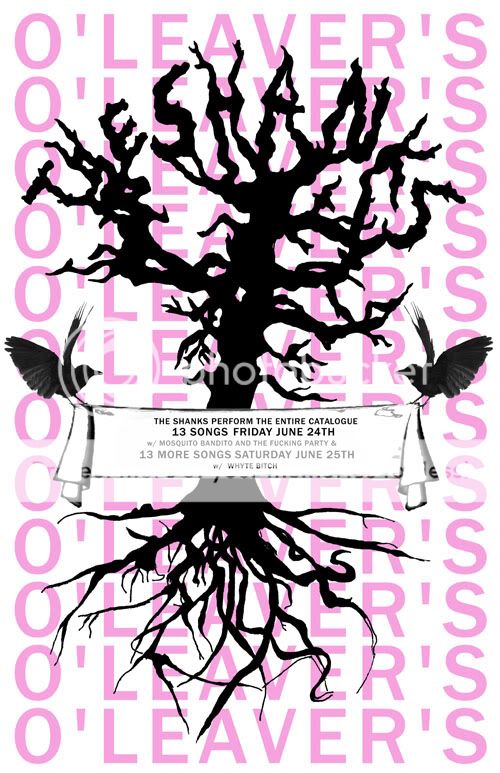

This isn’t how the band wants to be remembered. So they're reuniting to play/scream their entire catalog over two consecutive nights at O'Leaver's this weekend. They want to put the past behind them and bury the band with a positive eulogy.

But if debaucherous concerts have left you with no memory of the Shanks — or if you’ve simply never heard of them — this isn’t how to begin the story. It should start at the beginning.

About seven years ago, guitarist Todd VonStup and drummer Jeff Ankenbauer decided to start a punk band — a really gritty, dirty, death-to-sound styled punk band.

“We wanted to destroy music, and do what we wanted to do musically,” VonStup says. “Punk and noise and garage — we just ripped off bands.”

With ripped-up guitars, dirty bass and gunshot drums, the Shanks had the classic punk lineup. Their vocals were shouted at the crowd in defiance of all tact or taste — exactly their aim.

It was rowdy. It was dangerously fast. It was classic, kick-ass punk rock done right.

“We wanted to do this kind of abrasive, sarcastic, dramatic, disruptive punk music,” Ankenbauer says, his punk-scarred voice scratching through the phone. “But with that, live, there was a lot of nudity, fighting, breaking of instruments.”

The Shanks' lineup had to change accordingly with their conduct.

“I joined after about a year of the band being around,” says bassist Johnny Vredenberg. “The first bass player didn’t really fit the lifestyle of the rest of the band. I did. Just that kind of hard playing, hard partying lifestyle.”

Things kept getting hairier for the Shanks. After playing some garages and bars around Omaha, the band started to develop a following. The crowds they attracted were almost as violent and deranged as the band.

This environment had its setbacks. The band was partying hard at every show, and starting to get sloppy and violent, even for them. Antics like fistfights and pissing into each others' mouths became commonplace. It was so over the top that artists began to show up at Shanks performances, certain the shows were premeditated and full of meaning.

“People called it performance art,” Vredenberg says, laughing. “Fuck that. We were trying to kill each other.”

The Shanks were living life in defiance of the world around them, and especially to defy each other. The tumultuous inner-working of the band escalated and became the band’s public image, and perhaps its greatest draw. But they knew what they were doing couldn't last.

“All of our lives were really messed up, and we had a lot of problems, personally,” VonStup says. “The years of not doing anything with our lives and destroying ourselves got to the point where, well … It got to the point where I wanted to do something with my life, and the chemistry of that band was extremely destructive.”

The Shanks kept playing for a couple more years, adding Austin Ulmer (ex-Brimstone Howl) on guitar in 2007, and touring as far away as Chicago. But after years of fighting and partying their lives away, the Shanks were starting to get tired.

“We had nothing to live for,” VonStup says. “Not like we were going to blow our heads off or anything, but like, we had nothing to look forward to. That band was just a great reason to get of town and go drink and fuck your life up and not give a shit.”

Finally, about two years ago, the band called it quits after a too-wild Chicago show. They haven't played together since, though the former members still pop up in Omaha punk lineups like Baby Tears, Peace of Shit and Scratch Howl, always moving around.

That’s how people remember the Shanks. It’s an exciting tale, but a sad one, with a stern moral at the end.

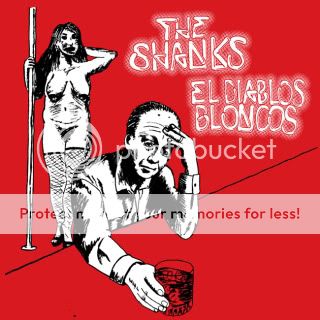

But again, this isn’t how the band wants to be remembered. While that entire wild tale was going on, the Shanks were making gritty, grimy, expressive, in-your-face punk music — and quite a bit of it, considering their relatively short tenure.

All told, the Shanks put together 36 songs of anarchic, defiant, defiling punk rock pulverization, and they want people to remember that. That’s why they’re going to try to put the past behind them and play two consecutive nights of shows this Friday and Saturday at O’Leaver’s in Omaha. The band will play 18 songs, half of their catalog, each night.

“We believe in the music, and a lot of people say they want to hear it,” VonStup says. “We believe these songs can stand for themselves. In the past, we really didn’t focus too much on playing them right when we played live. This time, I’m not saying it’s going to be a flawless performance, we’ll probably fuck up a bunch, but we’ll play them for what they are.”

For the shows, Ankenbauer will be exclusively on lead vocals, instead of drums. So the band brought in longtime friend Jeff Lambelet to pound the skins for what they say are their final two shows.

“I’ve known these guys since 2006,” Lambelet says. “They called me up and immediately I said, 'fuck yeah. I’ll do it.'”

Still, this band carries a lot of negative memories for the members.

“It’s kind of always a disaster when they get together,” Lambelet says. “It’s kind of good this is the end of it, in that way.”

There’s still a chance tensions could flare and things could go right back to the way they were two years ago. Each of the Shanks admitted they are all friendly with each other now, but each said that anything could happen.

“There might be a few instances where someone might look ready to punch someone in the face,” Ulmer says. “I think we can contain that, though. I think we can put it behind us.”

The Shanks want to make their music outlast their embattled past. They might want to prove that to themselves, as well.

“We want to look back and say we did ourselves justice, that we worked our asses off, and we just want to play a good rock ‘n’ roll show,” Vredenberg says. “We took the time to make these songs over the years, so we want them to be remembered. It’s how we want to be remembered, for them.”

Casey Welsch is an editorial intern at Hear Nebraska. He plays bass better than Sid Vicious, but so does everyone else. You can contact him at caseywelsch@hearnebraska.org.