by John Wenz

Typically, Echoes zeroes in on the music that has resonated in Nebraska throughout the years. But today, it's less about music, and more about a part of a nationwide movement.

Prior to the times of Epitaph Records and the Vans Warped Tour, punk was very much an underground thing. Sure, The Ramones had some videos on MTV, and "120 Minutes" might show the video to "TV Party" by Black Flag. But at its most "mainstream," punk was still largely a novelty to the widespread audience, relegated to misfits in the underground.

People attribute 1991 as "The Year Punk Broke" because a long-haired dude who couldn't cut it in The Melvins was bringing alternative to the supposed mainstream — nevermind that Nevermind was coming from a major label, and new wave had brought a mom-and-dad acceptable brand of underground in the '80s. That same year, one of the last true movements in punk was rumbling in the D.C. scene.

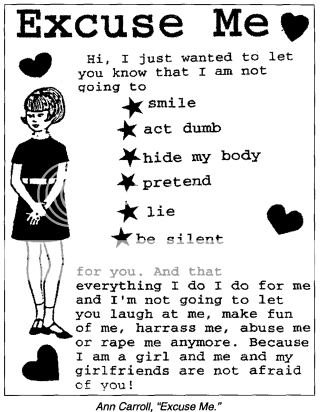

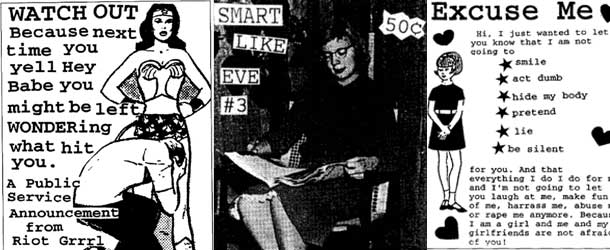

That was riot grrrl — a movement going beyond the female-fronted, third-wave feminist bands (Bikini Kill, Bratmobile and dozens of others) and into individual community groups and locally produced zines. There were frank discussions — of misogyny in local scenes, of sexual assault, of the right to choice, of the important issues facing a generation for whom second-wave feminism never resonated.

So it wasn't the music that struck Omaha. It was the ideas formenting under the idea of Riot Grrrl, in three high-school-aged women.

Monica Brasile would write later of her involvement:

I was a senior in high school in 1993 when some friends and I decided we were riot grrrls. It was a decision we made in a single moment, driving around after school one spring afternoon. I sat in the back seat with Andee as she read us a letter from a friend who had recently moved to Olympia, Wash., one of the major hubs of riot grrrl organizing. Living in Omaha, Neb, we weren't quite sure what inclusion in this group required, but the zine produced by the Olympia group, What Is Riot Grrrl, Anyway? gave us 25 answers to this question, all from different grrrls, making it clear that there was no prerequisite.

So Andee Davis, Ann Carroll and Brasile started their group. Gender violence, in its varying forms, were the topics of discussion. Eight girls attended the first meeting.

Zines also grew out of the Riot Grrrl Omaha group, with titles like Goddess Juice and Smart Like Eve. And after a Piqua, Ohio, convention failed to embody the spirit Carroll and Davis had hoped for in the new activist network, they ended up deciding to throw a Riot Grrrl Omaha convention in July 1994.

They released an announcement: "Hey Girlfriends," it said. "Us girls in Riot Grrrl Omaha are trying to get a girrl power convention together here in Omaha for next summer. A get together for girls to share ideas and empowermennt. So far our ideas are to have workshops, discussions, camping, a girl rock extravaganza and basically an amazing weekend with amazing girls."

Nomy Lamm, an Olympia staple, was set to perform, as well as Diamonds Into Coal, a band featuring Mary Fondriest and Erika Reinstein, two zinester friends of the Omaha Grrrls. Lincoln's XXY and Carroll and Davis' band Sweet Tarts were also put on the bill.

As grrrls from nationwide began to filter in, a strange tone was being set. As Sara Marcus' excellent Riot Grrrl history, Girls to the Front, put it, "… most of these girls were from the coasts. Their clothes were crazier, their hair was dyed flashier colors and arranged in more daring styles, and their whole attitude just screamed, 'Are you radical enough to be talking to me?' They were far more interested in catching up with their old friends than in paying any attention to their hapless hostesses."

Marcus reported things getting off to a bad start on Friday night, with Omaha band Pressure Drop — a mostly male band who were never invited on to the bill, but showed up and strong armed their way into playing — alienating much of the audience. Contrary to the riot grrrl message of uplift and empowerment, Pressure Drop rallied around a sort of PC neutrality of gender that tried to reduce the difference of genders to one of anatomy — nevermind the experiences women encountered that were far less frequent with men. They went as far as distributing a flyer with mutilated figures declaring "Without genitals we're all the same." Marcus wrote, "Stoking her hope, Ann approached the nearest bunch of girls and asked them for help making the boys leave. But they were too absorbed in their conversation to help."

Prior to the event planning, Brasile had found herself trapped in an abusive relationship, and disconnected from her friends. When she discovered she was pregnant, she broke off the relationship, and decided to carry the pregnancy to term. "After the most mentally and emotionally wrenching months of my life, I decided I was going to have the baby," she said. "I knew this decision meant that I would probably parent alone, but I was still harboring a hope that everything would change and we could be a healthy family somehow. Pregnancy gave me a renewed respect for myself, however, and the abuse became increasingly more intolerable to me."

So when Carroll and Davis organized an abortion clinic escorting time for the Saturday morning of their convention, Brasile, now free of her abusive relationship and working on repairing her strained friendships, came with her four-month-pregnant belly emblazoned with "Mothers For Choice." Davis set up for workshops, while Carroll's mind was set on many of the attendees who had decided to skip that morning's activities.

A workshop on class devolved into discussions of those who felt they shouldn't feel bad over their inate class privilege. "Other participants remembered the class workshop as important and eye-opening, despite the disruptions," Marcus wrote. "But for Ann and Andee, it was just one more thing in a string of disappointments that wasn't finished yet."

That "yet" was the evening's camp-out, in which participants complained that the fee they paid for the festival didn't cover the $5 cost of the camping. The camp-out contentiously went on, but both Davis and Carroll were mentally checked out, tired from the stress of the weekend. Brasile had a more positive take, saying, "We camped on the Platte River and swam and barbecued tofu and veggies. We sang and talked and traded zines. I made friends and fantasized about keeping them forever, but truly I felt very separate, because of my pregnancy and because of the greater context of my life in which this was happening." This was the tail end of the Riot Grrrl Revolution — and the end of Riot Grrrl Omaha. They ended up moving to Lincoln, while Brasile had her son that December, leaving her abusive relationship for the final time.

She would write later of the lasting importance, "Feminist activism is as important now as it ever was, and I doubt that any of my old grrrl-friends have become apolitical. For all of us who have silences that are yet to be broken, the powerful voice of riot grrrl is still resonant. Its assimilation into mainstream culture was inevitable in spite of the efforts to prevent it, but perhaps the 5-year-olds in their "girl power" T-shirts will be the ones to pick up where we left off and include a little of what we left out. In the meantime, I'm still striving for revolution-mom style."

And this will lead somewhat into our final part in this series for National Women's History Month, the status today of women in the music scene.

John Wenz is the listings editor for Hear Nebraska. In 1994, he was 10 and still a year away from his first CD, Hootie and the Blowfish. He can be reached at johnwenz@hearnebraska.org.