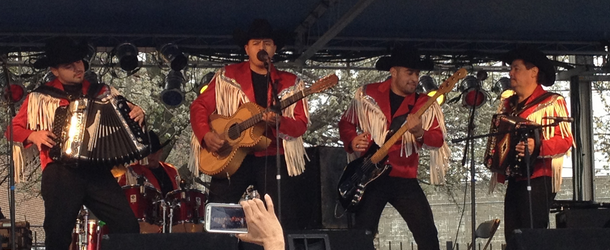

photo courtesy of Cinco de Mayo Omaha

I spent last Sunday in South Omaha to participate in the celebration of Cinco de Mayo. The South Omaha part is not peculiar, but my reason for being there is. I have never celebrated Cinco de Mayo, for the same reason that I have never celebrated St. Patrick’s Day: I am neither Mexican nor Irish. My familiarity with both holidays is shaded by the incomprehensible habit of getting drunk on holidays I’m not sure we fully understand. I don’t know exactly what I expected from Cinco de Mayo, but I didn’t anticipate feeling so entirely comfortable, so familiar.

I found the sorts of vendors and attractions that I expect of any street fair. And like most festivals, if you are the kind of person who wants to see and do a bit of everything, you’ll need a full day to see most of it — two if you have kids. The family stage on South 24th Street poured music down the carnival midway, where children flocked to a booth to have their faces painted before descending on all the classic games and rides. And all along the midway were booths offering art and souvenirs, clothing and jewelry. The beer garden faced the main stage on La Plaza de La Raza where bands played and women danced throughout the day. You will stuff your face and go to sleep with a belly full of traditional Mexican dishes. (One booth sold mangoes on sticks, a snack that seemed particularly ingenious to me because I lack the skill necessary to eat the fruit without covering myself in that sweet, sticky goo — not to mention the intelligence to remember where the odd pit hides.)

***

So there was the music, and there was the food. There was the dancing and the face-painting and the rides and the booths stocked with ponchos and soccer balls, and jewelry beaded and woven in every color. But more than all this — or perhaps because of all this — there was a perceptible but unquantifiable sense of community, a feeling of “us” stacked high and wide.

This feeling recurred throughout the day on Sunday, the Fifth of May, as I lazed along in currents of festivalgoers. It was there when I watched the tiny girl — 3 years old by my best estimation — perched on her father’s shoulders. Her legs were strapped in with his large hands while she pulled the trigger of her toy gun, unleashing swarms of translucent bubbles over the heads of the people around her. With each spray she giggled, and so did those around her. The feeling was there in a brief exchange between my friend Christina and two men when she pulled an unused folding chair to where I sat and the men hollered at her, “That’s our chair!” before smiling and laughing and returning their attentions to Los Terribles del Norte who had recently taken the stage.

In the hours after leaving the festival, I have been acutely sensitive to the fact of that feeling of community lingering with me, a gentle but persistent reminder of something I am unaccustomed to: blood membership, a belonging contingent only upon the decision to show up. My international (but entirely European) bloodline is indicative of my long-held belief about what it means to be white in the United States: I have not felt a particularly strong sense of ethnic or cultural community throughout my life because historically what it means to be white is in many ways also what it means to be American. Perhaps the closest I have come to a cultural identity was my childhood in Minnesota where the Norwegian blood in me was in close proximity to others who shared a similar lineage. But everything I know of Norwegian culture I learned as an adult, and I don’t like lutefisk, gelatinous fish prepared with a caustic chemical.

***

In the notebook I carry with me, I wrote this: “Los Terribles del Norte set — no applause between songs (?)” This fact warranted notation simply because I have been in attendance at enough concerts during which musicians reproached the audience for insufficiently expressing approval of the performance. During the summer 2011 Flaming Lips’ concert at Stir Cove, for example, Wayne Coyne repeatedly instructed the crowd to “Come on, motherfuckers” — an order intended to raise the energy, to make it a good show, and resulted in a set punctuated by long intervals of banter between songs. This was an extreme example of the sort of the exchange I’m familiar with, a rapid give-and-take between artist and audience — each song its own performance, a conversation between musician and listener.

On the other hand, it is generally considered inappropriate to applaud between movements of a symphony for the simple reason that in reality the performance is a single sustained piece. According to this tradition, the movements of a symphony rely on one another, accumulating, making connections, telling a larger story. Thus the audience must wait until the end to decide how to respond. It is for a similar reason that no one applauded between Los Terribles del Norte’s songs: the songs built onto one another to create the concert, songs often moving seamlessly into one another and creating a sense of movement. It wasn’t until the band had finished its concert that the crowd around me clapped and hollered — in appreciation of not only each song as a moment but also the story those accumulated moments told.

***

I have been confused in my understanding of Cinco de Mayo. Its meaning, according to the public school systems I went through, is like that of the United States’s Independence Day. Like the Fourth of July, Cinco de Mayo celebrates the cause for freedom and democracy, and like the Fourth of July, Cinco de Mayo has come to include beer and grilling food. The comparisons miss the point entirely, and I have begun to fill in the holes.

Cinco de Mayo commemorates the day on which the Battle of Puebla was fought in 1862, when the Mexican Army achieved an unlikely victory over occupying French forces. But this is not the holiday to celebrate the occasion on which Mexico secured its freedom — that is Mexican Independence Day, celebrated on September 16, the anniversary of Miguel Hidalgo y Castilla’s 1810 speech given in the small town of Dolores, the speech which marks the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence: the Grito de Dolores, the “Cry of Dolores.” Cinco de Mayo is localized, celebrated primarily in the United States and in the Mexican state of Puebla. It is not a holiday marking a definitive change in the nation’s history (the French would defeat the Mexican Army in later battles); rather it is a holiday to celebrate being Mexican.

So at my first Cinco de Mayo celebration, I was introduced to a wholly different sort of holiday than I have come to expect as a product of American culture: one that is plugged into Mexico’s national identity — and the identities of those who claim it as home — but also it is a holiday sung, sprung from within people, not governments. It is, in other words, a day of Mexican heritage and pride. A day of songs and food, and connecting with one another to tell a story. A day of little girls riding their fathers’ shoulders, blowing bubbles into crowds of people, and giggling.

S.R. Aichinger is a Hear Nebraska intern. This is his first story of the summer. Reach him at sraichinger@hearnebraska.org.