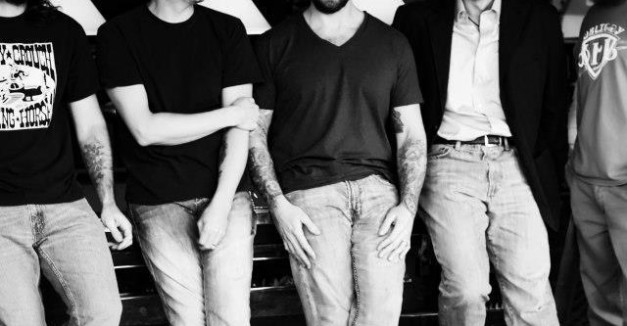

Jason Boland and the Stragglers

Tickets: $15, available 3/7 at 10:00am

It’s admirable when a musician gets back to his roots, there’s no questioning that. But in a lot of ways, it’s even more admirable when an artist has no need to do that – having never lost touch with those roots in the first place. Jason Boland falls squarely into the latter category, having spent the better part of the last 15 years entrenching himself in the so-called “red dirt” of his native state of Oklahoma and adopted home in Texas and while spreading his musical branches to cover a remarkable amount of territory.

“I’ve always thought it was important to keep one foot in tradition and the other pointed in the direction you want to go,” says Boland. “I didn’t invent the G chord, so I’m standing on the shoulders of the giants that did, and on the shoulders of some great songwriters that have come before me. I’m using an old stencil, but adding my own colors.”

On their new studio album, Dark and Dirty Mile, Boland and his compatriots use a wide array of hues to illustrate 11 songs of rejection and redemption, dark clouds and silver linings, all assembled in the rough-hewn manner that’s earned him an ever-growing fan base – a following that’s snapped up more than a half-million records over the past decade and change.

Dark and Dirty Mile is a song cycle of sorts, one that finds Boland seeking – and finding — beauty in life’s often-overlooked places, learning tough lessons through experience and overcoming obstacles with the help of others. That’s evident in the title track, which opens the album with a vividly drawn emotional landscape strewn with moments of regret and missed opportunities – but a clear bead on a clear horizon.

A similar dichotomy rolls through “Electric Bill,” a slow burn of a honky-tonk tune that conjures a picture of a man with an overdrawn checkbook in one hand and the hand of a loved one in the other – a sentiment he credits to his wife, who he says, reminded him that, “if everything is taken away tomorrow, there’s still love and hope in the world.”

Boland presents that sentiment without a drop of Hallmark saccharine, however. He doesn’t sweeten these tunes with easy studio tricks or the sort of pop trickery so often heard on Music City productions these days. The surface is anything but slick, and the sinew that runs through songs like the organ-tinged strut “Green Screen” and the high lonesome desert tone of his take on Randy Crouch’s “They Took It Away” lends a tone that’s ragged-but-right, ideal for Boland’s always-incisive lyrics.

“People don’t always expect to have a lot there in terms of lyrics,” he says. “Society says ‘if it sounds like this, you have to do songs about that.’ But if you just try to fit things together in the most simple way possible, you’re just trying to manipulate people, and I’m not interested in doing that.

“I think of myself as being in the Oklahoma tradition in the same way as Woody Guthrie – those of us who came up in Tornado Alley can all trace our lineage back to Woody.”.

Boland has been mining that territory for pretty much his entire career. Bowing in 1999 with the regionally popularPearl Snaps – a first teaming with Lloyd Maines, who Boland cites as one of several seminal influences on his sonic vision – the Stragglers built a rabid following from the Panhandle to the Gulf Coast. Over the intervening half-decade, the band would team with similar kindred spirits – from Billy Joe Shaver to Dwight Yoakam compadre Pete Anderson to the late Bob Childers – to create an uncompromising body of work, as whip-smart as it is body-moving.

“We’ve always been lucky enough to work with people who feel the same way we do about things,” says Boland. “The world doesn’t always make sense, but you meet people around the campfires who will be there for you. That’s the big secret, 99 percent of people will share and break bread with you when times are hard.”

Boland himself says that he started to figure things out in earnest around the time he and the Stragglers went into the studio to record 2008’s Comal County Blue, a set that, as Country Weekly put it, “vividly chronicle the thoughts of a regular guy trying to make sense of the world and only occasionally succeeding, while keeping one eye on the reasons he keeps trying.”

That disc brought Boland’s songs to a wider audience than anything he’d done in the past, but the momentum was slowed a bit by his need to take several months off to recover from surgery to remove a polyp from his vocal cord. He took the setback in stride, and now says, in retrospect, “it was a good thing in some ways, since it helped teach me to really sing and broke me of the habit of yelling – which is an easy habit to develop if you come up singing in Texas honky-tonks.”

By the time 2011’s “palpably redemptive” Rancho Alto (to quote the Austin Chronicle) came around, Boland had a firm rein on his instrument, which had grown into a burnished, evocative baritone, and further honed his pensive-but-not-pedantic writing style – all of which comes to heady fruition on the Shooter Jennings-produced Dark and Dirty Mile.

From the steeliness of “Only One,” with its unflagging belief in love in the face of adversity to the wistful regret of the album closing “See You When I See You,” that strength shines through. It emerges in the two-step friendly rhythms of “Nine Times Out of Ten” and it burrows deep into the soil on the soulful swing of “Lucky I Guess” – songs that evoke the sight, smell and taste of the red dirt of his home territory.

“The t-shirt sellers love that phrase ‘red dirt,’ because it’s so simple,” says Boland. “But it fits. It was coined by the people making the music – rust in the ground, blood in the dirt. It’s real and it’s where I come from – and what I refuse to give up, no matter what.”