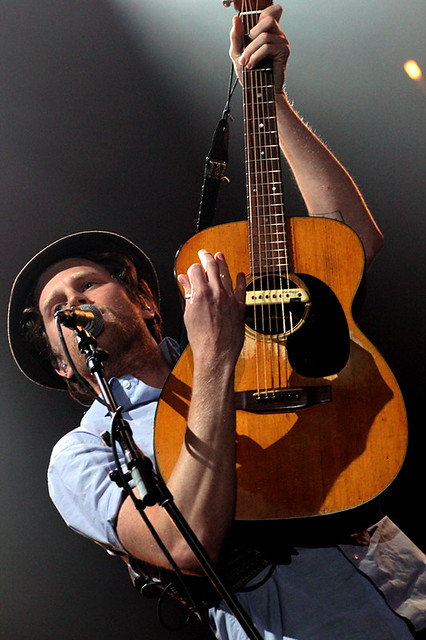

photos by Lindsey Akiyama

by Chance Solem-Pfeifer

It felt like an unfortunate but necessary step to stop people from getting struck by lightning.

When the announcement came down on Wednesday that The Lumineers’ sold-out show at the Pinewood Bowl Theater would be moved to the Pershing Center, it was meant to protect the audience from the elements or from being sucked into the mud of Pinewood’s grassy standing room.

Bummer? Sure. But the Pershing folks would have liked the show to be outside, too. That’s why they booked it there.

A “rain or shine show” isn’t a “get electrocuted” or “ruin our concert venue’s grass” show. That’s precisely why the parade of negative Facebook comments on the Pinewood, Pershing and Lumineers pages was understandable in emotion, but mostly unwarranted.

Still, Lincoln concertgoers — at least the demographic that was looking forward to The Lumineers and Cold War Kids — appeared to be more anti-Pershing than Pancho Villa circa 1916. And though I can’t say I’m on that train, the move indoors was a decision that would color the night from start to finish.

A crowd of more than six thousand spectators would eventually gather, but it was closer to two thousand when J Roddy Walston & The Business took the Pershing stage around 7:45 p.m. Their performance was, without a doubt, representative of the distractions and limitations that would hamper the rest of the night.

Here was Walston, a tornado of shoulder-length brown hair and green flannel, pounding blues rock into his piano and belting his heart out. And you couldn’t hear a single note of it over guitarist Billy C. Gordon, who was easily twice as loud as the piano and the vocals when he was playing a time-keeping rhythm pattern meant to fall underneath the lead parts. When Gordon soloed, he was three times as loud.

Now, undermixed vocals are a common issue at rock shows, but with Walston, it was comically hard to watch. He waved at some 2,000 people, encouraging them to sing with him, making hand gestures that correlated to lyrics no one could hear, drowned out by a lightly strummed guitar chord.

“Hopefully, they do better with Cold War Kids,” said a woman standing on the floor behind me, between the sets. I agreed and wanted very badly (I still do) to know who “they” actually were.

“Yeah, I just felt really bad for that band,” her friend answered.

Cold War Kids’ Nathan Willett dealt with similar issues a bit better, if only because of his famously powerful voice and great range. But unless you were familiar with guitarist Dann Gallucci’s parts, it took the singing crowd to make songs like “Hang Me Up To Dry” and “Hospital Beds” fully recognizable. Many of the really tuneful tracks from Cold War Kids’ most recent album, Dear Miss Lonelyhearts, were lost in the shuffle, as the vocals came off the stage flat and distant.

These issues weren’t night-ruiners for an applaud-first, critique-second crowd that was well-represented in the 16-25 demographic near the stage and by a very substantial family crowd in the Pershing seats. But they were very serious limitations on the totality of the event.

For instance, Billy C. Gordon’s guitar playing was intricate and shredding, reminiscent of Allman Brothers melodicism and Angus Young spitfire. But who can pull away how impressive the licks were from how they didn’t fit in with the soundstage of the band even a little? By that same token, Cold War Kids were a joy to watch careen around the stage, shoving and kicking each other. (Really, bassist Matt Maust repeatedly kicked Willett and Gallucci on the backsides with all the hilarious, masculine camaraderie of a high school football team captain warning his team not to blow it). But it would have been nice to hear Willett’s voice not sink out of the songs and into the corners of the arena.

Let me say for the second time, I don’t know who was responsible for these sonic mishandlings. But they were noticeable. And when you consider the escapist motivations people take into nights with their favorite bands, noticing shortcomings not in the technical performance of the band, but in the arena infrastructure is a problem.

Looking only at their performance, The Lumineers then brought lively dancing and clapping and throwing sticks and shakers at bass drums. It was great to see them not look exhausted from touring the same songs non-stop from The Grammys to small bars to the Lincoln arena over the last year. They moved touchingly back and forth between the crowd pleaser “Big Parade” for the encore and frontman Wesley Schultz doing the aching songs, like “Slow It Down,” all on his lonesome. And the beautiful quintet of jewel-adorned chandeliers rising and falling above the stage added a feeling of both celebration and the texture of old-timey nostalgia to the performance.

But with the move to the Pershing Center, The Lumineers were confronted with a difficult balancing act all evening long: the same one that could dog them all through the summer if they’re not on a festival billing surrounded by other comparable acts. As wildly successful as their debut self-titled album has been — it’s still the 17th most downloaded album on iTunes and it was released on April 2012 — they’ve ridden the still-strong wave of just those 11 beloved songs the whole time. Which is impressive in its own right.

Sidenote: The one-hit punchline of “Ho Hey” that detractors will vocalize is not only unfair and reeks of anti-popularity elitism, but anyone at the show on Thursday who thought the band used their big hit as a crutch is making an incorrect observation. The Lumineers played the song third in their set. It was a very apparent attempt to dig into the rest of the album without slighting the song — to get it out of the way. Not playing the FM radio hit as the last song of the encore works as an implicit request that attention should be paid to their body of work — the whole album, not the song made famous, in part, by Silver Linings Playbook and car commercials.

Still, the album, The Lumineers, boasts a recorded running time of 38 minutes. Swap a few instruments add a few clapping interludes and we might be at 45 minutes for a live show. That’s why even conceptually the move to the Pershing didn’t work for The Lumineers. Outside at Pinewood, with the feel of a miniature festival, everyone can play for about an hour. The Lumineers, with their summery folk pop and single album, probably benefit the most.

But put them in a 6,000-person arena where headliners routinely play for two hours and the first two acts haven’t hit home with their full force, and suddenly one hour — of the record, one Bob Dylan cover of “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and some pleasant, but unrecognizable new tunes you couldn’t hear Schultz introduce — doesn’t seem to fill the space.

And it’s tough to say if the sound problems were fixed. The audience mostly overpowered the vocals on the songs from the album. The Lumineers did their best to create an intimate setting in a venue that resists it by going out into the crowd. But the chance to mingle with fans in the middle of the floor may not have been worth the two-song trade in sound quality. Even on the main stage, woven harmonies sounded like bring-the-roof-down choruses. Neyla Pekarek’s cello was hard to find, even if her big smile and soulful vocals on the new song, “The Duet,” weren’t.

Back outside, it was extremely clear from the lightning that appeared around 6:30 p.m. on Thursday night and from the photos of the waterlogged mudhole the Pinewood space became, that The Lumineers concert could not have been held there. The responsible choice was made.

And would all the sound issues and loss of detail have been remedied if the show was held in the planned spot? There’s no way of knowing. There will always be unknown variables at work for a concert production of that size. At a show, the audience doesn’t know who’s behind the controls, if he or she had time to adjust to a new space or if the Pershing acoustics are just difficult to navigate. Roadies and sound engineers were certainly planning for Pinewood, though.

Optimistically, the show was a well-played “what might have been” reminder of all the important factors that go into making a large production seamless. A sound guy does his job when no one notices him. A venue does its job when no one has to think about how well its acoustics support three very different live bands.

When people leave a concert, no one wants the question of professionalism to come into their heads. They should be thinking about which song was their favorite or at what moment they forgot when they had to be to work the next day, the moment they felt togetherness with the others in the room.

The minute the question of whether or not a show was professional is raised, The Lumineers ceased to be an experience. What’s left is scattered, scrutinized parts. It’s only a band and a body of work, a stage and a building, a backup plan and the final question: Who didn’t hold up their end of the bargain?

Chance Solem-Pfeifer is a Hear Nebraska intern. He strongly recommends giving J. Roddy Walston & The Business a fair listen. Reach him at chancesp@hearnebraska.org.