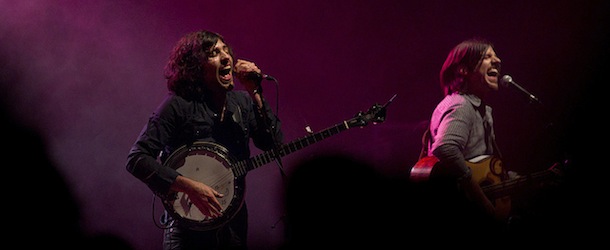

photo by Matthew Masin

Scott Avett likes his songs to surprise him, even if it’s not always pleasant.

“Sometimes songs are a shot in the dark … a threat, more of a gamble,” Avett says. “They come and they visit for a little bit. They’ll betray you. You’ll spend all morning on an idea that seems so perfect and so great and by the time the end of the time you’re working on it, it seems like it never was good after all. They’re like mirages, you know?”

The elder Avett brother (banjo/vocals) cites this in-song volatility as the reason the forthcoming record with his younger brother Seth (guitar/vocals), bassist Bob Crawford and cellist Joe Kwon is still dramatically taking shape.

On separate occasions, they’ve described their follow-up to The Carpenter as both a companion to the 2012 album — which advertised a more refined rock sound compared to the brothers’ early rip-roaring country folk — and its still-mutating extension.

But for at least the moment, Scott says the songs on the fall album are revealing themselves to him as a “closer” for The Carpenter, the conclusion and, perhaps the undoing, of many of themes constructed on the last record.

“Since we recorded the songs, all of our lives have changed,” he says. “So these songs mean new things. So in a way it’s kind of like a closing or a breaking down. In a way, a restart.”

Hailing from Concord, N.C., The Avett Brothers began recording and touring their hard-charging, harmony-heavy folk in 2000, but didn’t find crossover success until the release of 2009’s I and Love and You, their first of two albums with famed rock and hip-hop producer Rick Rubin.

Since taking it up with Rubin, the band played The Grammys in 2011, alongside Bob Dylan and Mumford & Sons, and performed “I and Love and You” on Jimmy Kimmel Live with the Brooklyn Philharmonic in the wake of Hurricane Sandy. In September 2012, The Carpenter peaked at No. 4 on the Billboard US charts.

The Avett Brothers will return to Stir Cove in Council Bluffs for the second consecutive summer on July 3. Tickets are available here.

But first, Scott Avett spoke via phone to Hear Nebraska about how the band’s forthcoming autumn record might be the antithesis to The Carpenter, why he thinks sculpting is the purest form of art and why it wouldn’t take much for him to write a “Pretty Girl From Nebraska” song.

Hear the full interview with Scott Avett here:

Hear Nebraska: People at this point must be pretty familiar with The Carpenter. When did you start to see people knowing all of the words to the songs on that album?

Scott Avett: Sure. I’d have to think for a second. I recall going to a show in the past two months where we performed and I was kind of taken aback at how much more familiar those songs were than the older songs. It was a festival show. I’m not exactly … I remember it was outdoors.

The strange thing is with the slow sort of growth we’ve had on everything, we’re so used to having diehard, longtime fans that they didn’t care what was more popular than anything else. They would just know so many songs and be so into them in a deep way. But this was kind of evidence of something else. But we’ve seen that grow kind of naturally since the album had been out. We experienced some of it in Europe when we went, as well.

HN: I wanted to ask you a little bit about continuity on The Carpenter. Because whenever I listen to it in the car, I’m always kind of struck by how the last track ends in the same key as the first track starts in. Like the last suspended chord of “Life” is almost resolved with “The Once and Future Carpenter,” which is a really kind of cool continuity, I thought. How important to you guys in the making of that record was the cohesiveness of the album? Or the “continuity,” if I can keep using that word.

SA: Yeah, well, sequencing for us and Rick (Rubin), we probably spent way more time on it than the public probably cares about now in the iTunes world or the single world. We’ve always looked at the album — still do as we move forward — as a whole and a work that needs to flow and work together like any visual, musical or any other type of composition. Architectural or anything.

So we worked really hard on that. We bounced back and forth with sequences — I guess we spent on both I and Love and You and The Carpenter two or three months pining over which songs should follow and how they should relate to each other.

So that’s very important. It’s kind of a testament to the space between is as important as the space within. And it takes years to figure out as a writer that that’s very important.

HN: Do you think you guys have gotten better about thinking on the scale of a whole album as you’ve gone on, thinking on a larger and larger scale? How has that happened?

SA: By default. I hope that we’ve gotten better at everything. But it’s never as good as it can be, ever. And I think that’s the element that we can trust and depend on: that we’re more in tune what we haven’t gotten good at than what we have. And I think for me personally more so in the group than anybody, as far as that’s concerned. I don’t want to congratulate myself or anybody else a lot of times because this is our work and we want to make it better. It’s for other people to enjoy. We need to move and get better at all those things.

But I do notice some things are easier than they used to be and inventorying verses choruses and songs as a whole especially comes more naturally than it used to.

HN: Well, I know you guys are getting ready for a record in the fall, and I’ve already read in interviews you were thinking about doing something else next year. So when you say you’re more in tune with what you have not yet gotten good at, what’s at the forefront of your mind as far as improving with these forthcoming releases?

SA: Well, you know, I’m really looking — I mean, there’s a lot, my plate is so full with this — I’m kind of thinking what do I pick to talk about? A lot of things are being revealed to me as I’m working through the upcoming release as well as what’s after that and how they all work together. And what do they mean? And how relevant do they need to be to where and who we are right now? Which is usually a priority to us.

I’m thinking in terms of that. And I’m thinking in terms of, “Wow, my mind might already be in 2015 or 2016.” And that can be a really bad thing. That can be done in vain and I have to pull back on it.

HN: Like the cart’s ahead of the horse? What do you mean?

SA: There’s no guarantee you get 2015 and 2016. There’s no telling what can happen between now and then. There’s no telling if you or I or anybody else for whatever reason might not be doing what we’re doing today. And I just have to remind myself of that and be aware of that and slow down and be in the moment. More so in the moment right now is the work of art I’m concerned about and considering is the setlist for tonight and how we’re gonna bring it to the crowd tonight.

But backing up to the question about doing better and making an album that’s better than the last, there’s a lot of approaches to recording that I think we want to take. We’ve dabbled in these live recordings where we all group together in a room and play the songs live and try to capture — kind of like Tonight’s the Night for Neil Young — that’s an approach we’ve thrown around for this next album because that’s something we haven’t done as much as we used to do. But anyway, the list is kind of endless. I don’t mean to get too detailed with it.

HN: With then, Scott, the record that’s coming in this fall, I’ve heard you guys refer to it a couple different ways. I’ve seen it referred to as a companion record to The Carpenter, but also as something different, something that is more of a follow-up, like the next step. How are you thinking about that forthcoming record right now?

SA: Well, once again, it’s kind of revealed itself as less of a companion and more of a closer, if you will. And it’s just strange how that happens, you know? You write songs and put them out there and record them and they mean something to you when you make them. This group of songs: some of the meanings have confirmed themselves with all the vigor in the world, in the most convicting ways.

And some have changed their meanings. And as we’ve seen that happen, we’ve added some songs. We’ve added two songs to this list that weren’t gonna be with this. And we saw it become something that was a surprise and we didn’t expect. And the album still remains to be kind of surprise to us. We’re watching it all fall in place now. I’m looking at it more as this closer, maybe breaking down what The Carpenter put up. If that sounds funny, it sort of does, but it’s kind of what’s happening.

HN: Breaking down what it put up?

SA: Sort of. We’ve talked a lot about The Carpenter and the concept of the The Carpenter was the building up of each other. The title came from a conversation that Bob and Seth had about how we hold each other up through all these things we do and we were looking for a symbol of that. We found “the carpenter” to have so many meanings. There were religious meanings. There were literal meanings. It was just beautiful and, of course, we had it within the song that I had written. It all made sense. In a lot of ways, it revealed itself and made sense.

Since we recorded the songs, all of our lives have changed. All of our lives in different aspects of the world have found themselves in different directions. So these songs mean new things. So in a way it’s kind of like a closing or a breaking down. In a way, a restart. It’s interesting. It really probably takes some articulating, but hopefully the album does that.

HN: OK, so breaking down. What would you call it? The Tornado or The Arsonist? What’s the enemy of the carpenter?

SA: (Laughs.) You get a good word. You send it to me, all right?

HN: (Laughs.) All right. Well let me ask you this, Scott, the fact that you’ve had some of this material ready to go. The fact that you guys are always working on songs over the course of years, you’re known for your tremendous amount of back material and you guys write in such a prolific way. But I’m curious about the other side of the coin. For a band that’s so adept at producing volumes of material, do you guys ever get writer’s block and what’s that like?

SA: We do. We do get writer’s block. But I guess both Seth and I are writing and we never put a hold or a filter on that. And the fact that we wrote a lot, we have a lot of backlogged ideas as well. I think we’re kind of so stocked up that if we had writer’s block, we’d just rework old ideas.

I had an art teacher in college that told me, you know, every day can’t be a creative day, that’s just the mechanics of it. So when it’s not a creative day and nothing is visiting you in your heart and your mind to create something new, well, then you stock up on canvases and stock up on material and you stock up on making sure your space and your preparation is good.

I can’t count the times I know Seth and I reinventory ideas we’ve had, revisit them. So if you’re not having new ideas, we go back and listen to old ones and we say, “Are these still viable? Are they still credible? Do they still matter?” And you’re always revising and refining what you have anyway. So there’s enough work really to last a lifetime in that regard.

HN: Well, let me jump to this because you mentioned art: Your artwork is known to your fans, clearly been a great passion of yours for some time. I like to ask people who do both audio and visual art, does your painting come from the same creative well as your music or is it somewhere different, do you feel?

SA: It is different. They touch. I think they run parallel some. They sometimes run closer to each other than other times. Some days they feel just worlds apart: a whole different practice. This week is good example of that.

I’ve spent the week paint and screen printing. I’ve just turned all the music off and all the noise and just had it silent in my studio. And that was really positive for me and really good. I get quite distracted by lyrics and ideas. Because when I listen, I’m not listening for enjoyment. I don’t go to a concert and have a party, I never have. I’ve always gone and folded my arms and watched and studied and been affected by everything so much, that it’s impossible for me. And I don’t think that’s odd for any artist. Visually, though, I have to say that when I’m painting — other than spending with my kids — it’s one thing I never question whether it’s useful ever. Ever.

It’s always of use to me. It’s always good work. It is different in that sometimes songs are a shot in the dark. They’re more of a threat, more of a gamble. They come and they visit for a little bit. They’ll betray you. It’s interesting. You’ll spend all morning on an idea that seems so perfect and so great and by the time the end of the time you’re working on it, it seems like it never was good after all. They’re like mirages, you know?

photo by Matthew Masin

HN: Sure. Like you mentioned, you and Seth spend a lot of time thinking about whether old songs are, I think you used the word “credible” or relevant. Why do you choose not to think about painting that way? Do you just need that outlet that you don’t have to question?

SA: Maybe. I haven’t thought a whole lot about that. I feel like as long as I know that I’m creating something or letting something out, it’s very much like playing golf in our own little worlds. We all do it in controlling ways. Sometimes we sweep the floor to control our setting, kind of like cleaning your world. When I’m painting, even if I’m not making something that will eventually be seen, I feel like I’m clearly getting better. I’m clearly improving myself. And learning something. I should just simplify that. I’m clearly learning something.

I don’t think anything more past that. Now, sometimes I just have to sit down. And sometimes this happens when I’m painting. Sometimes I have to walk away, take a pen and my pad and just write for a little bit and get something out. I don’t really question, I’ll do it whenever it calls, period. But I guess if it feels like a little more dependable form of art.

I believe that sculpting, three-dimensional work, is probably, I’m convinced — maybe i’m not convinced of this 100 percent — is the purest form of art possible. There’s less to hide behind. There’s less to hide behind than any other art.

There’s different levels for me in music. There’s several things you can choose to hide behind and I think those are good things. Distortion can be a great thing to hide behind and it can also be a great thing to reveal and learn from, but as you strip down it comes down to, “What has been created here and why is it good? And does it entertain and does it move a person?” And painting is another level of pure art, but I feel like a sculpture as you can walk all the way around it, could be the purest form.

artwork by Scott Avett

HN: Yeah, you can see every angle.

SA: Of course, probably the purest, purest form of creation is out of your hands. The purest form of creation is birth and what’s made in nature, but we don’t have anything to do with that, but we make our own. The sculpture thing is interesting to me, and a painting is step toward that because you have to sculpt with it.

But once again, huge topic. (Laughs).

But I do think about these things when I’m writing. Lyrically, these metaphors are very important to me. I do use them. I think about them quite a bit.

HN: I can tell you think about it. I’ve seen that you do a lot of self-portraits, and I’m curious to some extent do the songs ever feel to you like self-portraits? Like versions of you that highlight different attributes and emotions, but aren’t the whole picture?

SA: Absolutely. You could probably say any song that an individual writes on their own is a self-portrait. They don’t have to be pictures of you to be self-portraits. You could paint a still-life and have it be a self-portrait if you wanted it to be, I suppose. And really in the end, they’re all reflections of ourselves.

Just like what everybody writes. I could write something: a tweet or in my head or book about someone else and it’s still a self-portrait. It’s still a reflection of me. It’s still my take, coming from my perspective. That’s a very interesting topic and one that I think about quite a bit.

HN: So when you take a song that’s personal or close to you and you take it to the rest of the band to collaborate — I’m thinking about something like “A Fathers First Spring” — when you take a tune like that to rest of the band or to Rick, how do you take notes on something that started out so personally? Do you have to separate the content from the presentation? How does that work?

SA: Sure, well, “A Fathers First Spring” is good example of that of one that, of course, that using my daughter’s name in it is kind of like stepping up to a cliff and throwing yourself off of it or even worse throwing your family off of it. I’ve been concerned about that.

But that aside, that being a reason not to put it out there, but people now and in history and that will come will experience what it means to have a child and what it feels like to have a child in their own way but also in similar ways to other people that it’s worth sharing. That is something that will bring interest and joy and a shared relationship with. I think that’s kind of what determines … you have to put it out there. You have to. Because it just matters.

“Murder In The City” was a song that I was like, “Ah, jeez.” It was so morbid sort of sounding, but it was very frank. It was very real. And the fears and the hope within the song were something that as a group — or at least between Seth and I — we knew it had to go out there regardless of what I was thinking or feeling. So, yeah, there’s a lot of risk involved to put the personal things out there. We learn more and more about that every year and work on our courage to continue to do that.

HN: Going back to the original question, how do you collaborate on something so personal. Do you have to just give it over and think about the presentation?

SA: Oh, all right. So this crazy thing has happened. This crazy thing is happening right now where there’s a list of songs that I got maybe half done, a quarter done, two thirds finished, which I’m just known for… (Laughs).

I passed them on a USB to Seth, and said, “Take a look at these. See if there’s something that strikes you on them if you want to write off of them or whatever.” I was gone from these songs. Some of them were somewhat abstract and metaphorical and loosely based on me. I might have taken liberties and just kind of let my imagination run wild.

This is within the past month. After passing those to Seth, he came back with this group of maybe five or six of these songs that were totally completed that he had found these things in these songs, where he was like, “These were written for me. They were totally written from my point-of-view and here you go and they’re finished.”

I was just reviewing yesterday, thinking this is unbelievable, it’s uncanny, it’s surreal to see these things now. And I don’t really want to talk too much about it because the songs are kind of on the dock for what do we do with these now? But it’s very interesting.

So that’s a way that some of those personal things — regardless of me saying how I abstract them — they’re still personal. I throw them out there and then Seth bounces off of them and what it’s doing is it’s really difficult to know who wrote what. Seth is singing on things that sound like they’re straight up from him. And I wrote them. It’s really strange to be the writer and listen to that be like, “This is confusing.” So it’s awesome connection with a family member that you would have.

HN: So this relates when you’re talking about the kind of giving over the personal. I’ll never forget when you guys were on Jimmy Kimmel singing “I and Love and You” right after Hurricane Sandy. Here’s this song you guys wrote years before, clearly not about a hurricane, and you have thousands of people and millions watching saying, “ This song is for us!” And so has watching your songs get bigger and reaching more people, does that require you to think of them as relative or constantly expanding.

SA: Probably. (Laughs). Maybe we should. I think we’re determined to keep on writing honestly and we know that’s a shot-in-the-dark thing. You don’t write in the hopes for that anyway. It’s such a tough thing. It’s hard thing for a lot of people. You hope that the songs inspire people, but it’s gotta be for the real reasons.

If it’s not for the real reasons, what a terrible, cruel joke that would be on yourself. So we try not to think about what a song could be or where it’s going or what does it mean to expand anymore than “this is what it means, this is how I’m putting it out there.”

I know it will mean many things to many different people and that’s fine. And however that ends up is good. It may not mean anything to a lot of people and that’s OK too. I think we have to keep it at the core and let it come from the core and then let go where it will be.

HN: Last one, I work for an organization called Hear Nebraska which promotes, writes about and supports all Nebraska music, so I’m curious what do we have to do here in this state to get you to write a “Pretty Girl from Nebraska” tune?

SA: (Laughs.)

HN: We have a lot of them. Do you need to be introduced?

SA: (Laughs). What town are you in?

HN: I’m in Lincoln. We have so many pretty girls.

SA: I believe it, I believe it. But, uh, I don’t guess it would take a lot. Probably just a “hello” or a nice glance and a handshake. You know, those songs have never been, most of them at this point aren’t really love songs necessarily. So any interaction can trigger such a thing. I don’t think it would take much.

Chance Solem-Pfeifer is Hear Nebraska’s staff writer. Scott Avett is a married man. So asking if he needs to be introduced to attractive women was definitely a one-last-question-for-you interview move. Reach Chance at chancesp@hearnebraska.org.